Is the NHS facing a perpetual winter?

- Published

There has been a new raft of warnings about the state of the NHS, suggesting it is now in a "perpetual winter" with patient demand relentless throughout the year.

By far the most significant is the intervention of hospital and other trust chiefs in England, with their message that "something has to give".

Usually the crescendo of voices calling for more money builds as the Autumn Statement gets closer and the winter pressures on the service begin to build.

But now, in early September, the chief executive of NHS Providers Chris Hopson, has chosen to break cover and fire his warning shot in the direction of Downing Street.

Its understood that his members wanted him to speak out even sooner.

Seven-day NHS 'impossible under current funding levels'

Is enough being spent on the NHS?

NHS weekend: 7-day services explained

Seven-day NHS - claims and counter claims

In essence, their message is that the service is stretched to the limit and that without extra funding there will have to be reductions in care on offer or rapidly increasing waiting times

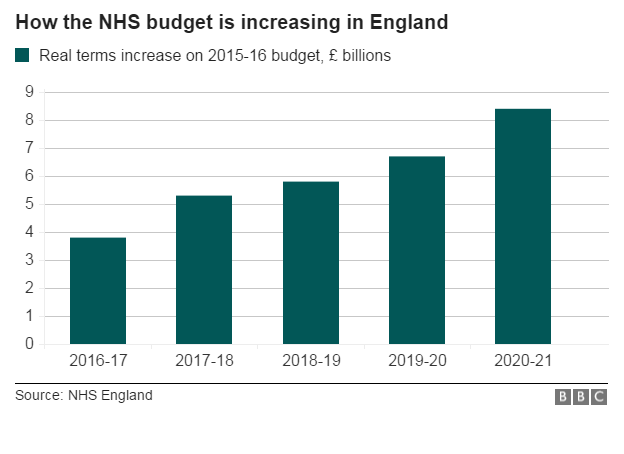

The government argues extra annual funding has been allocated to the NHS in England, rising to just over £8bn by 2020 - and that has come on top of an extra £2bn in 2015-16.

Ministers argue that this is what NHS leaders asked for and accepted as reasonable.

What's more, they say, the £3.8bn extra for this year was greeted as a generous "front-loaded" settlement.

So the spotlight has turned on Simon Stevens, head of NHS England, with some asking whether he did not ask for enough when he settled with the former Chancellor George Osborne.

NHS leadership unhappy

I understand that the NHS leadership was not best pleased with the outspoken comments from Mr Hopson on Sunday morning.

The hope had been to keep the NHS under the radar for now.

The problem for Mr Stevens is that only in July he unveiled a plan to help hospitals and other trusts bring down their annual deficits.

It was branded as a "reset" after hospital finances had appeared to be out of control in the previous financial year.

Chris Hopson has ruffled NHS leaders' feathers with his warning

Announcing a relaxation of the fines regime and new agreed spending totals for each trust, Mr Stevens said: "We need to use this year both to stabilise finances and kick-start the wider changes everyone can see are needed."

Now, less than two months later, those same hospitals are saying that only an extra injection of funding or a radical rethink of the way the NHS provides care will suffice.

NHS England sources suggest there was never a demand for a specific cash sum in 2020.

Instead, Mr Stevens set out a range of scenarios when he unveiled his Five Year Forward View in 2014. , external

Between £8bn and £21bn was requested, and if it was to be at the lower end of the range then extra help for social care, funded by local authorities, would be required.

There has been a sharp increase in the number of elderly patients stuck in hospital beds because social care arrangements are not in place to allow them to return home.

In an interview in the last few days, Simon Stevens has revealed more of his thinking about the financial challenge.

Speaking to Health Policy Insight, he acknowledged there had been an upfront financial "kick start" in the current year.

But, he said, "we didn't get our proposed funding profile for the next three years", so as things stand these years are "obviously going to be tougher than we originally asked for".

He also noted that the NHS had got less capital investment than envisaged in the five-year plan set out in 2014.

Government sources are discouraging any thoughts of more money being stumped up for the NHS in the Autumn Statement - not least because of the pressures on public spending across Whitehall.

They expect hospitals to continue with efficiency savings to make best use of the money already allocated to the service.

But Prime Minister Theresa May and Chancellor Philip Hammond know that health is high on the list of voter concerns and that any deterioration in standards could become politically toxic.

Meltdown warning

The Society of Acute Medicine has warned that the NHS could experience "pockets of meltdown" this winter and that medical units will be "put to the test as never before".

Add to all this the claim by NHS Providers that the seven-day NHS policy for England is unworkable without more resources, and a key plank of government policy is under increased scrutiny.

It has been a central issue in the junior doctors' dispute and will be contested more vocally as strikes planned for October draw closer.

Ministers argue that the seven-day NHS is a manifesto commitment and that more effective urgent care can be provided at weekends within existing budgets.

But the prime minister as well as the Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt will come under more pressure to explain their plans.

Health could well become the most important domestic policy challenge for Downing Street as autumn turns to winter.