Coronavirus: What is the hidden health cost?

- Published

Michelle Gray had her healthcare procedures cancelled because of the coronavirus pandemic

The rising death toll from coronavirus is never far from the headlines, but hidden behind the daily figures is what public health experts refer to as the "parallel epidemic".

This is the wider impact on people's health that is the result of dealing with a pandemic.

UK chief medical adviser Prof Chris Witty has been referring to this with increasing frequency during the daily briefings, speaking about the "indirect" costs of coronavirus.

But what is it, and how significant could it be?

Not getting NHS care

The focus on ensuring there were enough beds in hospitals to care for coronavirus patients led the NHS to carry out a series of unprecedented steps.

Routine treatments, such as hip and knee replacements, were cancelled across the UK. This alone will have a significant impact on people's lives, though it is unlikely to kill anyone.

Prof Derek Alderson, of the Royal College of Surgeons, said this will be having a "major impact" with patients left in pain and suffering disability.

The backlog in surgical work will be "gigantic", with more than 700,000 routine treatments a month affected.

The pandemic has also had a knock-on effect on emergency care.

Data collected by Public Health England from a sample of A&E departments in England shows attendances have halved since the pandemic started. The trend has prompted NHS leaders to urge patients to come forward for treatment.

NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens has urged people to use the health service when needed, and this week Health Secretary Matt Hancock signalled he wanted to see services slowly restored.

The fear is that people who are suffering serious problems, such as heart attacks and even strokes, may be put off seeking treatment.

There is evidence this has happened for children too, with doctors reporting children were being brought in late with conditions such as ruptured appendixes and blood poisoning.

Disease and illness not being prevented

The most obvious fear is over cancer - screening has been suspended in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland and drastically cut back in England.

Cancer Research UK estimated that a drop-off in both screening and urgent referrals from GPs meant 2,700 fewer people were being diagnosed every week.

Richard Sullivan, professor of cancer and global health at King's College London, said the impact on years of lost life "could be quite dramatic", given cancer patients tend to be younger than those dying of coronavirus.

It has been announced that thousands of cancer patients will be operated on at new centres designed to be kept clear of coronavirus, in a bid to address the problem.

But this is not just an issue for cancer.

Breast screening is just one of many ways of picking up cancer

Others have pointed to the difficulties people with chronic conditions like diabetes or kidney disease may face trying to manage their conditions remotely without the regular face-to-face contact they would have with health professionals.

School vaccinations have been paused and while pre-school programmes, including the MMR jab, are still being offered, there is concern there may be a drop in uptake.

The UK had already lost its World Health Organization measles-free status before the pandemic.

'Perfect storm' for mental ill-health

It should not come as a surprise that people report finding lockdown difficult.

A recent Ipsos MORI poll found half of people felt anxious or depressed, with one in seven saying they were unable to cope.

The issue has also been raised by a group of 24 leading psychiatrists and psychologists in a paper published in the journal Lancet Psychiatry.

Rory O'Connor, one of the report authors, says increased social isolation, loneliness, health anxiety, stress and an economic downturn are a "perfect storm" to harm mental health and wellbeing.

The Institute of Health Visiting has warned about the impact on vulnerable families in particular.

Health visitors have been forced to carry out nearly all their work remotely, either on the phone or via video technology.

The IHV said it was worried that the early signs of a host of problems, from child abuse and domestic violence to maternal mental ill-health, were being missed.

Calls to the National Domestic Violence Helpline have risen by half three weeks into lockdown.

How many lives could be lost?

Health experts say the best way to judge the impact of this is to look at the total number of people dying to see if that is going up.

This information is published by the Office for National Statistics in England and Wales and its counterparts in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

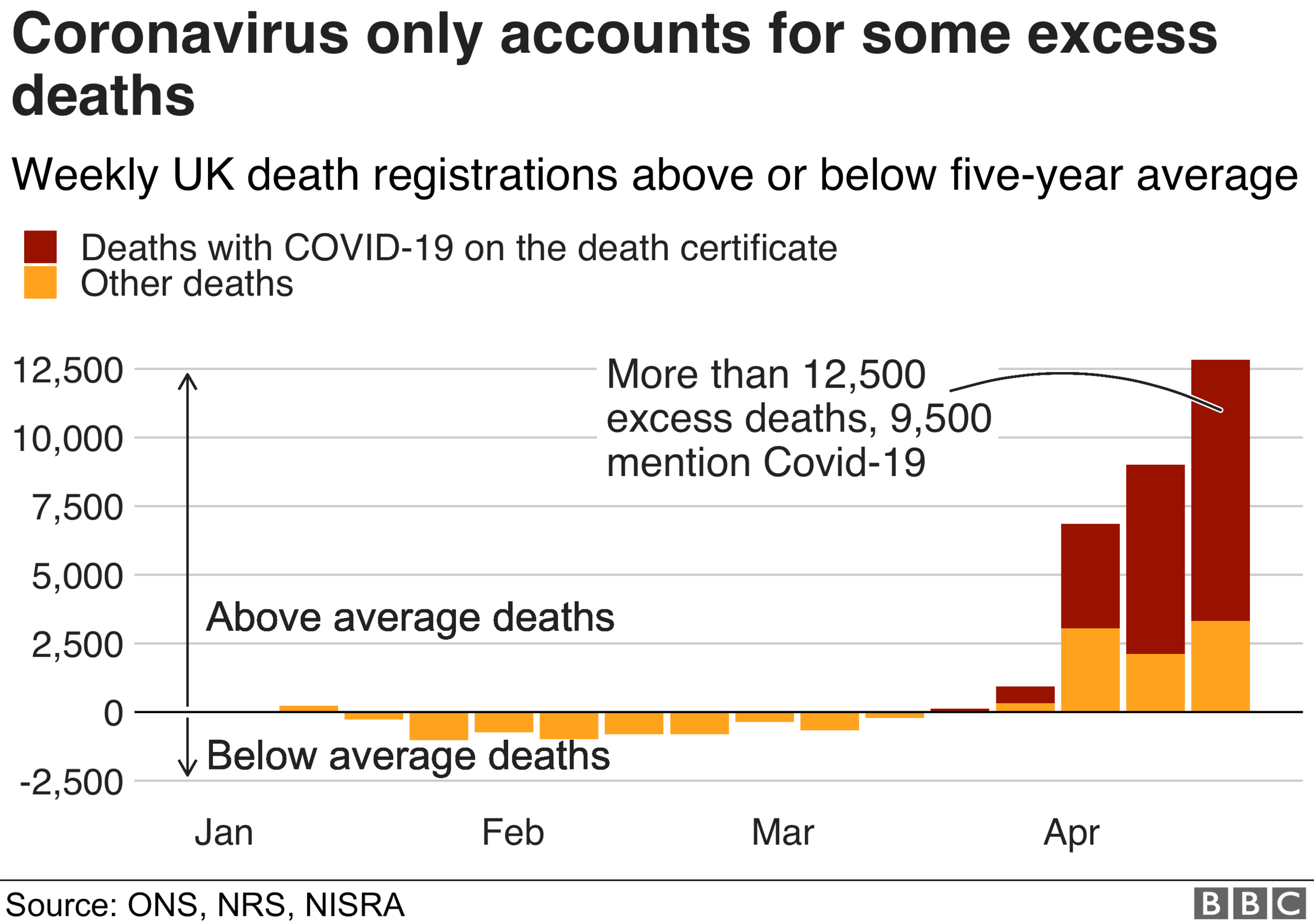

Before the outbreak really took hold in the UK, the number of deaths was below the average for the previous five years.

But, according to latest figures, the number of deaths is now more than 20,000 above that average.

Coronavirus is mentioned on some of these death certificates, but certainly not all.

Under-reporting of the virus could certainly be a factor, but it does suggest the indirect cost may be having some impact.

The full impact could take years to unravel

While some of the indirect impact on health is immediate, a lot may take years to become apparent. Later diagnoses for conditions like cancer may not show up in death figures for another year or two.

Other consequences of the pandemic could take even longer to emerge.

An analysis by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, external noted that economic downturns have an impact on health as well as wealth.

It said the relationship was "complex" but that increased unemployment, falls in income and uncertainty over jobs would have an affect on health in the long term.

It pointed to research showing a 1% drop in employment leads to a 2% increase in chronic conditions, such as obesity and diabetes, with the poorest in society the most at risk.

University of Bristol researchers have tried to quantify this even further. They have said the benefit of a long-term lockdown in reducing premature deaths could be outweighed by the lost life expectancy from a prolonged economic dip.

The tipping point, they say, is a 6.4% decline in the size of the economy - on a par with what happened following the 2008 financial crash.

It would see a loss of three months of life, on average, across the population.

- Published16 April 2020

- Published29 April 2020

- Published30 March 2020

- Published4 August 2019

- Published6 January 2019

- Published8 February 2017

- Published8 February 2017

- Published6 January 2017