Coronavirus: How scared should we be?

- Published

Coronavirus has been described as an invisible killer. What could be more terrifying than that?

A deadly pathogen we cannot spot, and then when it hits, we cannot treat.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that many people are fearful of going out, returning life to normal or even letting children go back to school.

People want to be safe. But the problem is we are no longer as safe as we once were.

There is, after all, a new virus around that can have catastrophic consequences.

The need to balance competing risks

So what should we do? Some have argued restrictions need to continue until safety can be guaranteed. But those arguments generally ignore the fact that continuing to do so carries risk in itself.

UK chief medical adviser Prof Chris Whitty often describes these as the "indirect costs" of the pandemic. They include everything from poor access to healthcare for other conditions through to rises in mental illness, financial hardship and damage to education.

So as restrictions ease, society and individuals themselves are going to have to make decisions based on balancing competing sets of risks.

Why you should not expect to be 100% safe

Prof Devi Sridhar, chair of global public health at Edinburgh University, says the question we should be asking is whether we are "safe enough".

"There will never be no risk. In a world where Covid-19 remains present in the community it's about how we reduce that risk, just as we do with other kinds of daily dangers, like driving and cycling."

She was referring to the row over schools, but the concept can equally be applied to many other scenarios.

She says part of that equation depends on the steps taken by government on things such as social distancing, the provision of protective equipment and the availability of testing and then tracing of contacts to contain local outbreaks. She has been critical of the way the government has handled all of them.

How much risk do individuals face?

But as more freedoms are returned, the role of individual decision-making will come more to the fore.

It is perhaps not about finding the right option, rather finding the least worst option.

Statistician Prof Sir David Spiegelhalter, an expert in risk from Cambridge University and government adviser, says it has, in effect, become a game of "risk management" - and because of that we need to get a handle on the magnitude of risk we face.

There are two factors that influence the risk we face from coronavirus - our risk of becoming infected and, once infected, our risk of dying or becoming seriously ill.

If we are not in hospital or a care home our best guide to the risk of infection comes from the government's surveillance programme run by the Office for National Statistics.

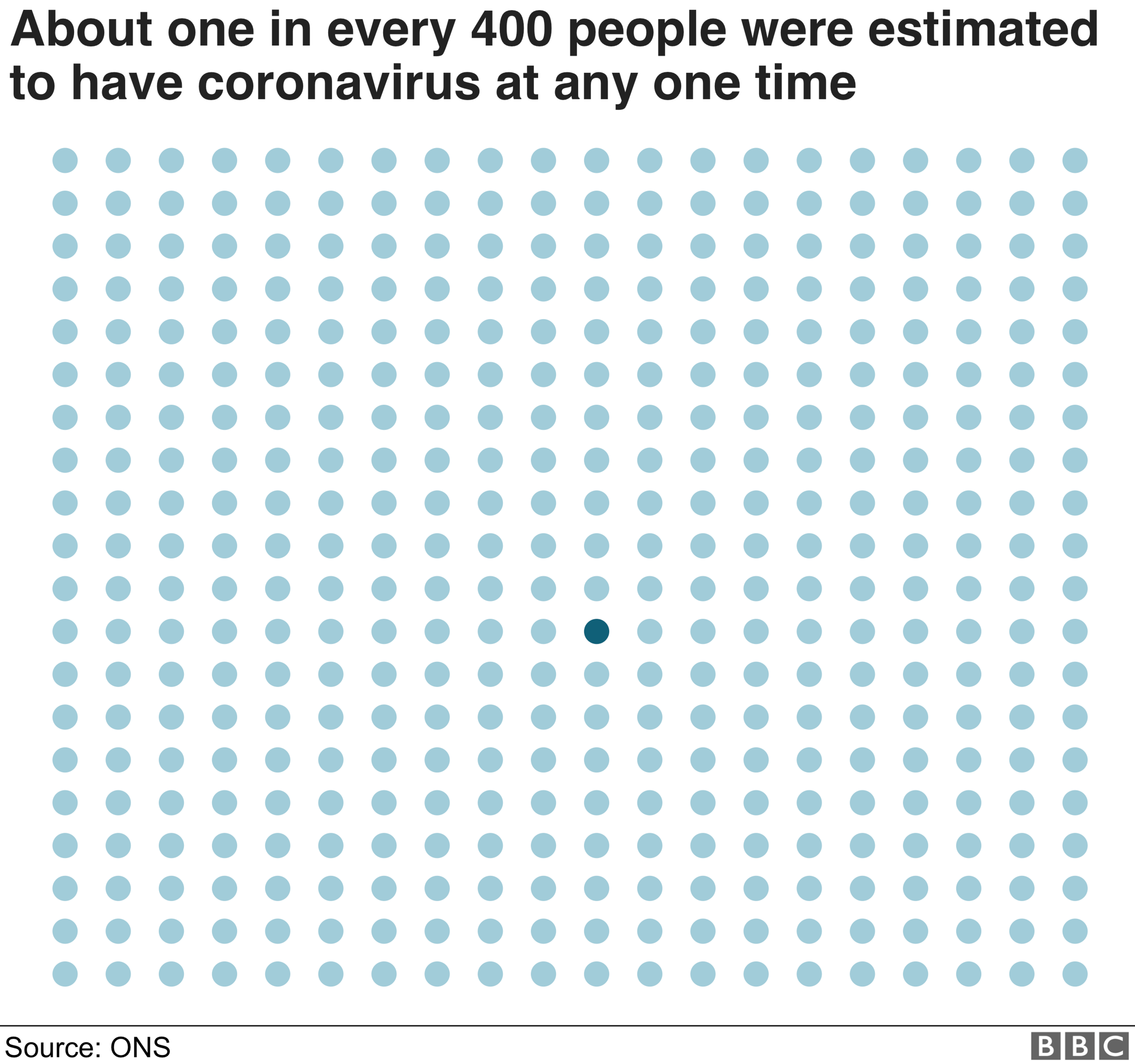

The data published this week suggests around one in 400 people is currently infected.

The chances of coming into close contact with one of those individuals - certainly as we are practising social distancing even when out and about - is considered to be pretty slim. Although clearly some people, depending on their jobs, are at higher risk than others.

The hope is that level of infection will reduce even further in time if the government's test, track and trace programme keeps the virus suppressed.

Then if we do become infected, the fact remains that for most people, coronavirus is a mild-to-moderate illness - only one in 20 people who shows symptoms is believed to need hospital treatment.

How to quantify your risk?

Those with pre-existing health conditions are most at risk. Deaths among under-65s with no illnesses are "remarkably uncommon", research shows.

Perhaps the easiest way is to ask yourself to what extent you are worried about the thought of dying in the next 12 months.

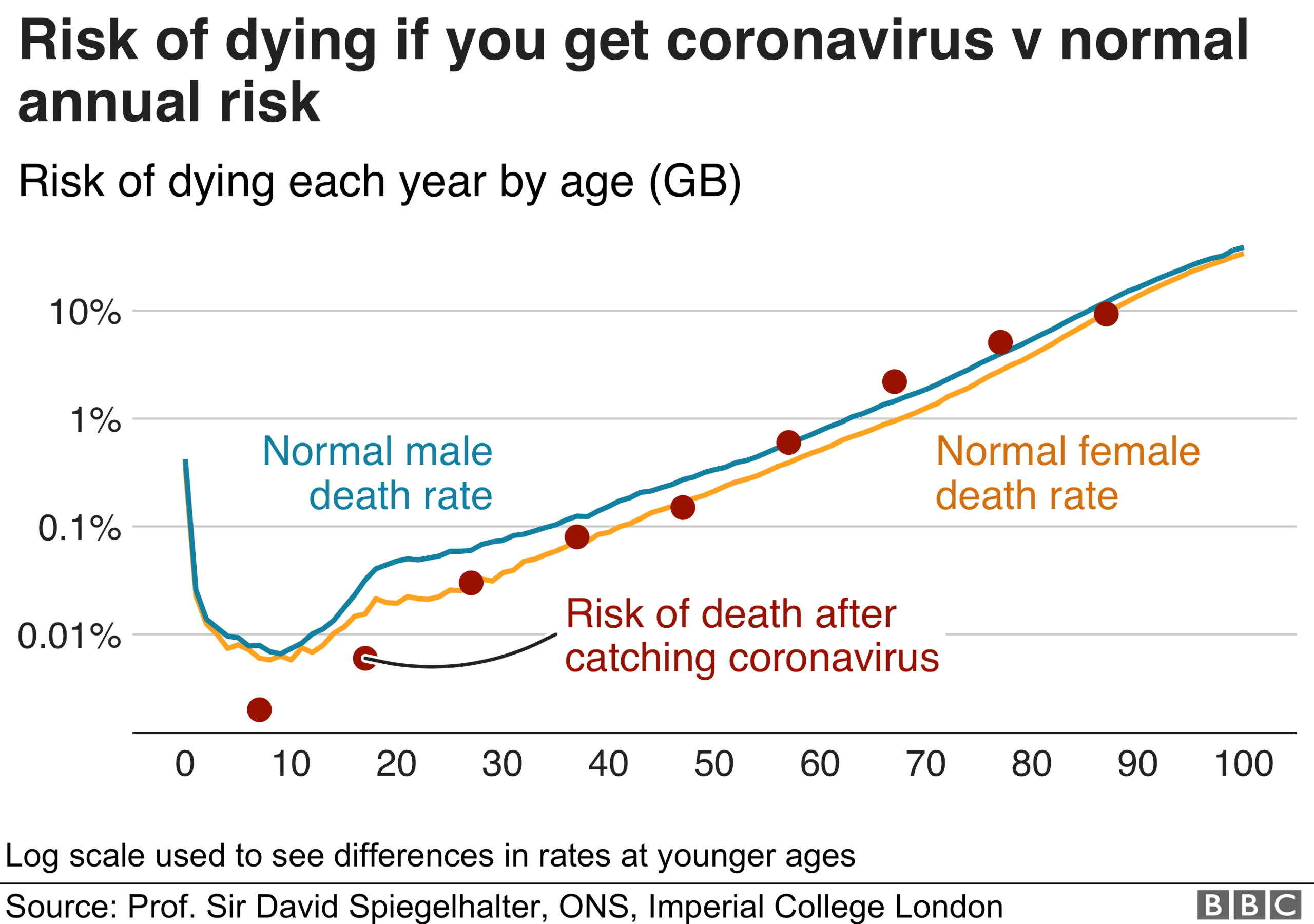

What is remarkable about coronavirus is that if we are infected our chances of dying seems to mirror our chance of dying anyway over the next year, certainly once we pass the age of 20.

For example, an average person aged 40 has around a one-in-1,000 risk of not making it to their next birthday and an almost identical risk of not surviving a coronavirus infection. That means your risk of dying is effectively doubled from what it was if you are infected.

And that is the average risk - for most individuals the risk is actually lower than that as most of the risk is held by those who are in poor health in each age group.

So coronavirus is, in effect, taking any frailties and amplifying them. It is like packing an extra year's worth of risk into a short period of time.

If your risk of dying was very low in the first place, it still remains very low.

As for children, the risk of dying from other things - cancer and accidents are the biggest cause of fatalities - is greater than their chance of dying if they are infected with coronavirus.

During the pandemic so far three under 15s have died. That compares to around 50 killed in road accidents every year.

Identifying those at risk

So what seems crucial as we all try to balance risks is identifying those at significant risk of serious illness from coronavirus - whether we fall into one of those groups ourselves or have close contact with someone who does.

Currently the government is asking 2.5 million people to completely isolate themselves. This includes people who have had organ transplants, are having cancer treatment and those with severe respiratory disease.

On top of those, there are more than 10 million people who fall into higher risk groups. These include all the over-70s and people with health conditions ranging from diabetes to heart conditions.

Prof Sarah Harper, an expert in ageing at the University of Oxford, has argued the "blanket and arbitrary use of age" needs looking at as the actual level of risk within this higher risk group varies enormously.

A tool developed by University College London, external has attempted to tease out some of the differences in risk.

Finding out more about these is going to be crucial as we move forward.

- Published16 April 2020

- Published29 April 2020

- Published30 March 2020

- Published4 August 2019

- Published6 January 2019

- Published8 February 2017

- Published8 February 2017

- Published6 January 2017