Have 1,200 World Cup workers really died in Qatar?

- Published

The scandal surrounding corruption within world football's governing body, Fifa, has focused fresh attention on the workers who have died building stadiums in Qatar for the 2022 World Cup. The figure of 1,200 deaths is often cited - but how reliable is it?

Living and working conditions for some migrants in Qatar are appalling. Long hours in the blazing heat, low pay and squalid dormitories, are a daily ordeal for thousands - and they cannot leave without an exit visa.

Qatar is clearly worried about stories getting out about the workers' suffering. A BBC team was arrested there just last month.

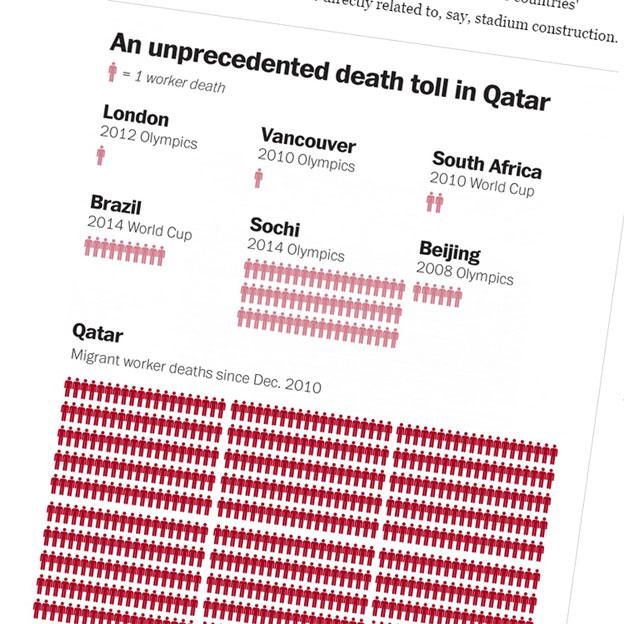

And many workers have died. A graphic published last week in the Washington Post, external now doing the rounds on social media contrasts the relatively small numbers who died building facilities for other recent international sporting competitions - from the Beijing Olympics to the Brazil World Cup - with the 1,200 said to have died already in Qatar.

But where does that figure come from, and how was it calculated?

It was first published in 2013 in a report by the International Trades Union Confederation, external, called The Case Against Qatar.

The ITUC went to the embassies of Nepal and India, two countries which are the source of many of the migrant workers who go to Qatar. Those embassies had counted more than 400 deaths a year between them - a total of 1,239 deaths in the three years to the end of 2013.

But Nepal and India account for only about 60% of the estimated 1.4m migrant workers in Qatar, so the total number of migrant worker deaths is certain to be higher.

The law firm DLA Piper, which was commissioned by the Qatari government to look into the issue, was given similar estimates, external for deaths of Indian and Nepali workers. It also obtained figures for the deaths of Bangladeshi workers - taking the death toll to almost 1,800 across the three years, or 600 a year.

A trade union-organised protest in Zurich on 29 May against workers' conditions in Qatar

But this would still be only part of the story, as Qatar is host to large numbers of migrant workers from other countries, from Egypt to the Philippines.

These workers aren't all building World Cup facilities, however. In fact most of them aren't.

A lot of them are construction workers building - well, pretty much anything that needs to be built around Qatar.

The ITUC believes that counting all construction work is legitimate.

It says that although the first World Cup stadium was only started last year, subways, hotels, and even an entire city are currently being built, not to mention an airport, numerous roads, a new sewerage system in central Doha and 20 skyscrapers.

"It needs to be remembered that the infrastructure programme in Qatar is entirely built around the delivery date of the World Cup in Qatar," says Tim Noonan, director of campaigns at the ITUC.

But it's hard to argue that if there been no World Cup in Qatar there would have been no construction. Qatar's economy tripled in size between 2005 and 2009, and a construction boom was already under way before the country was awarded the 2022 World Cup. To blame football for all the construction deaths in the country is surely stretching it.

Another factor that needs to be taken into account is that, according to one estimate, a third of migrant workers in Qatar don't even work in construction. The ITUC, though, is counting the deaths of workers in any line of work and from any cause, including road accidents and heart attacks.

Some would argue that it was a bad idea to hand the World Cup to a country where so many migrant workers are dying - even if some are dying on construction projects unconnected with the World Cup, and others are dying in unrelated sectors of the economy.

But the Indian Government says in a press release: "Considering the large size of our community, the number of deaths is quite normal."

The point officials are making is that there are about half a million Indian workers in Qatar, and about 250 deaths per year - and this, in their view, is not a cause for concern. In fact, Indian government data suggests, external that back home in India you would expect a far higher proportion to die each year - not 250, but 1,000 in any group of 500,000 25-30-year-old men. Even in the UK, an average of 300 for every half a million men in this age group die each year.

Tim Noonan from the ITUC believes the comparison is misleading. The migrant workers in Qatar are not only young, they are fit. "Qatar requires them to be given a medical examination to screen them for pre-existing conditions, so this is comparing apples and pears," he says.

Of course, India is a very poor country and Qatar is a very rich country - the richest in the world in terms of GDP per capita - so it's perfectly reasonable to say that Qatar should do better by its migrant workers. But then it is.

So is the figure of 1,200 Qatar World Cup deaths just meaningless? No, says Tim Noonan. He denies the ITUC came up with the figure just to get headlines. In fact he thinks the real figure may well be higher.

"To describe a problem is the correct thing to do," he says. "And we believe we've described it accurately and conservatively."

More from the Magazine

A Fifa taskforce has recommended the Qatar World Cup takes place in November and December 2022. Previously it was claimed pioneering cooling technology would allow it to happen in the summer. So what has changed?

What happened to the Qatar World Cup's air-cooling technology? (February 2015)

Listen to More or Less on BBC Radio 4 and the World Service, or download the free podcast.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.