The lion: A victim of its own power?

- Published

Lions have padded their way through history, their beauty and physical prowess inspiring fear and respect. But despite a fascination with the creatures, humans have managed to wipe out one type of lion completely, writes Mary Colwell.

The lion motif appears on the insignia of kings, cars, chocolate bars and rugby shirts - the giant media company MGM has famously used the roaring creature as its logo since 1924.

Lions are among the most popular subjects for natural history films, where every nuance of their lives is explored in detail. We never tire of the thrill of a hunt or seeing cubs playing around a dozing adult.

Leo the lion, the star constellation of the outgoing and showy, prowls the night sky. The embodiment of power and wealth, lions symbolise physical beauty, muscular prowess and majesty.

Find out more

Natural Histories is a series about our relationships with the natural world

Listen to Lions on BBC Radio 4 on Tuesday 30 June at 11:00 BST or online after broadcast

Historically, Barbary lions, a sub-species of the Savannah lions, were particularly prized as the male was large and sported a long, thick black mane. The hair stretched from the head to the belly, giving it a magnificent profile. Everyone who wanted to show the world they had power wanted a Barbary lion.

Roman emperors desired them as pets and gladiators often found themselves face-to-face with them in the arena. Spectators revelled at the sight of human courage pitched against the embodiment of elegance and strength. The savagery of the lion made it a perfect agent of execution for criminals and Christians.

Detail of a mosaic depicting the biblical story of Daniel in the lions' den

In medieval England Barbary lions were kept in the Tower of London. Their cages were so close to the entrance - Lion Gate - that no visitor could enter the realm of royalty without first staring into the amber eyes of a lion. The message was clear - this ruler even has the magnificent lion under control.

The skulls of two male Barbary lions were found by workmen in a moat in the Tower in 1937. Carbon dating puts the animals as living between 1280 and 1385, giving us a glimpse of the physical condition of animals that lived in London 700 years ago.

It turns out that the poor beasts were inadequately fed and malformed, dying at an early age.

The hole where the spinal cord enters one of the skulls is deformed. "That should be a nice, well-formed, sub-circular shape," says Richard Sabin, curator of mammals at the Natural History Museum in London. "But you can make out that at the top of the hole there's an infilling of bone, it's actually a pathology, a reaction to potentially some sort of nutritional stress. As the bone grew it would have put pressure on to the spinal cord and caused paralysis and blindness."

Not that this mattered to those who came to stare at them. What visitors saw was the epitome of majesty.

One of the skulls found at the Tower of London © The Trustees of NHM, London

The deformed hole in one of the skulls © The Trustees of NHM, London

In the medieval mindset a lion was soaked in Christian meaning - it represented Christ the King, and it was firmly believed that lion cubs lay without form or identity in their den for three days after birth until they heard the roar of their father, which imbued them with life and energy. It was a clear reference to Jesus lying in the tomb waiting for his Father to call him to new life.

The physical splendour of lions merged with the power of God and the grandeur of kings, gave medieval lions a unique position.

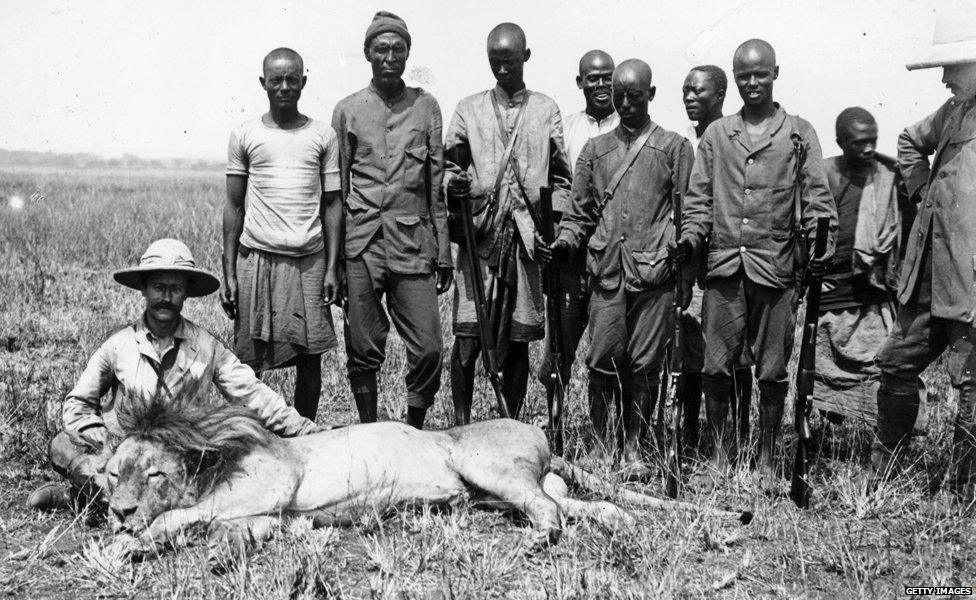

But the desire to own lions, Barbaries in particular, meant many were taken from their natural home in North Africa, and over the centuries their numbers fell dramatically. The invention of the gun and the popularity of sport hunting in the 19th Century further reduced numbers and the last wild Barbary lions were shot in the mid-20th Century.

The power of the lion, so desired by the elite of Europe, was its undoing.

Current research, external suggests there are no pure Barbaries left in captivity - but there are discussions about bringing them back using DNA from closely related species in India, or selectively breeding captive lions that contain Barbary genes.

The question remains though - why? Even if technically it were possible to see a pure Barbary lion once more, it would only ever be a curiosity and would never be able to roam North Africa again.

"Can we recreate their natural environment or has that changed for ever?" asks Sabin. "Or will they just be isolated examples of their species in a zoo that people pay to see?"

Today, the closest many people get to Barbary lions is in Trafalgar Square in central London, where four males cast in bronze guard the foot of Nelson's Column. Designed by Landseer and installed in 1867, they remain a poignant reminder of our power to destroy what we most admire.

Richard Sabin, though, believes the remains of the dead Barbaries still have a role to play. "We decimated them and pushed them into extinction. The fact that we hold their remains in our museum collections means researchers have the opportunity to extract data and put them into a modern context and look at closely related species that may be heading for extinction and potentially halt and slow those extinctions."

A frieze depicting an ancient Assyrian lion hunt circa 700 BC

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published23 June 2015

- Published16 June 2015

- Published9 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015