The beautiful creatures with a deadly streak

- Published

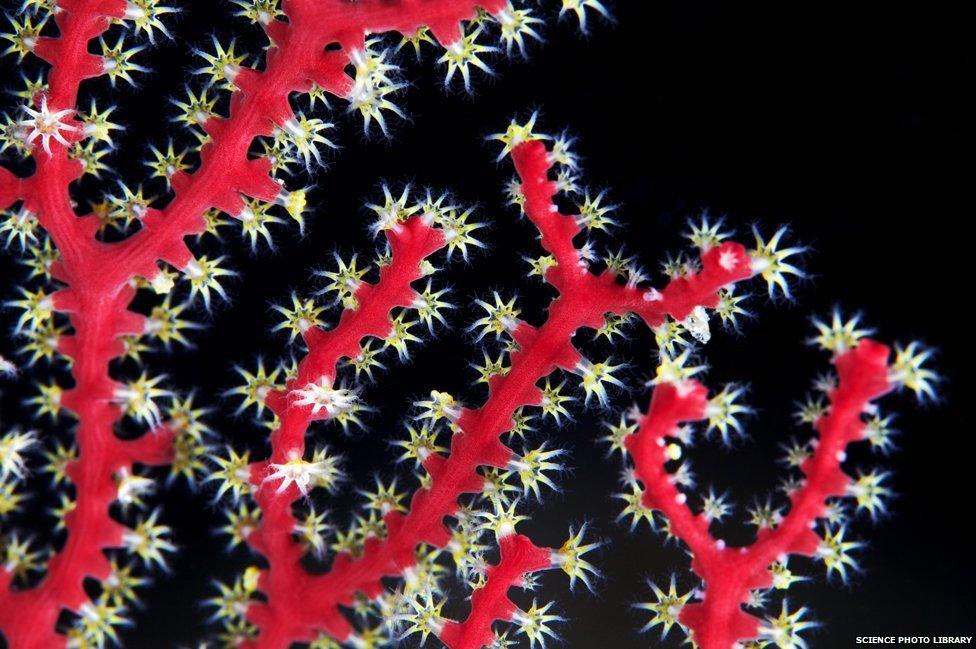

The shimmering beauty of a tropical coral reef submerged in a sapphire sea is often equated with paradise. But there's a darker side to the idyll, writes Mary Colwell.

Coral reefs "are beautiful places", says Ken Johnson, a researcher specialising in coral at the Natural History Museum in London. They have "complex, three dimensional structures like cliffs and turrets" with a huge diversity of life. "We see schools of fish and many types of corals, and overall the sense is of colour and movement."

Reefs often surround coral islands where white sands are lapped by gentle waves - R M Ballantyne captured this idyll in his 19th Century novel The Coral Island, a tale about 3 boys who are sailing through the Pacific Ocean.

"At last we came among the Coral Islands of the Pacific; and I shall never forget the delight with which I gazed - when we chanced to pass one - at the pure, white, dazzling shores, and the verdant palm-trees, which looked bright and beautiful in the sunshine. And often did we three long to be landed on one, imagining that we should certainly find perfect happiness there!"

Other writers, such as James Montgomery, saw virtuous industry on a reef, where millions of animals and plants work tirelessly together to create a harmonious whole - a fitting model for human civilisation. He captured this notion in his poem Pelican Island in 1828.

"With simplest skill, and toil unweariable, / No moment and no movement unimproved, / Laid line on line, on terrace terrace spread, / To swell the heightening, brightening gradual mound, / By marvellous structure climbing tow'rds the day."

Every tiny polyp of the coral and all the attendant creatures are involved. "Paradise gradually developed from the toil, as they called it," says Ralph Pite, professor of English literature at Bristol University, "just as the successful British society and great empire developed out of the toil of individual workers in their factories and homes."

Science, however, has prompted a reality check on our image of paradise, which is not all it seems. A coral reef can also be seen as a wall of mouths. Each tiny polyp is a predator that can extrude its stomach on to neighbours if they get too close and digest them in situ. It can create a web of slime to trap small creatures that float by or grab them with tentacles and drag the victim to its stomach.

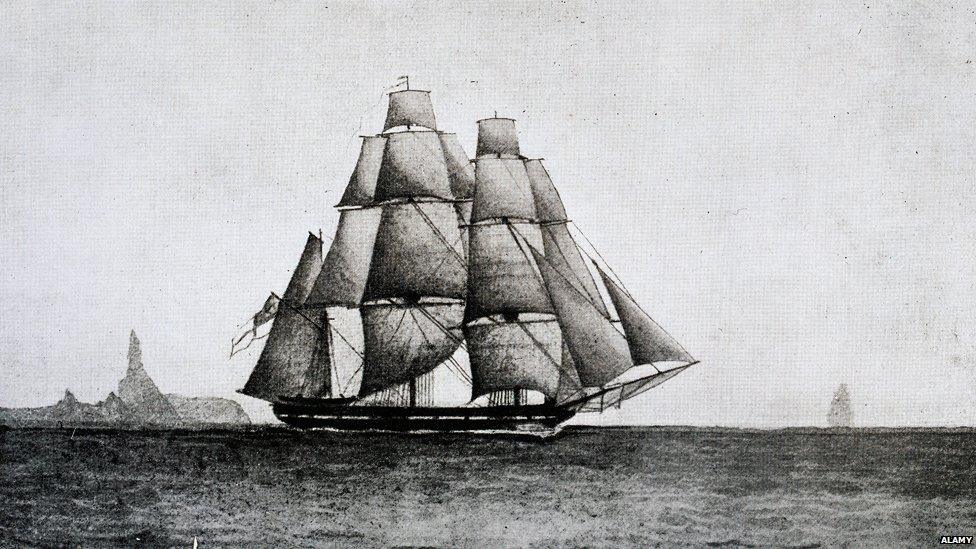

HMS Beagle was tasked with mapping coral reefs

Humans may be too large for such techniques, but many a ship, including Captain Cook's HMS Endeavour, has foundered as hard coral skeletons, made up of calcium carbonate, have ripped through their wooden hulls.

So dangerous were coral reefs to shipping, that in the 1830s the Beagle, with Charles Darwin on board, was sent to map coral islands in the Pacific to help reduce the damage. Darwin's first book, The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs, published in 1842, was on the mechanism of their formation.

Find out more

Natural Histories is a series about our relationships with the natural world

Listen to Coral on BBC Radio 4

As more was discovered about coral reefs, especially with the advent of diving, deeper canyons were explored and a new image emerged.

"The coral reef starts to be similar to the dangerous urban spaces of the Victorian world where down alleys and back streets, in dark corners, all sorts of dangers might lurk," says Ralph Pite.

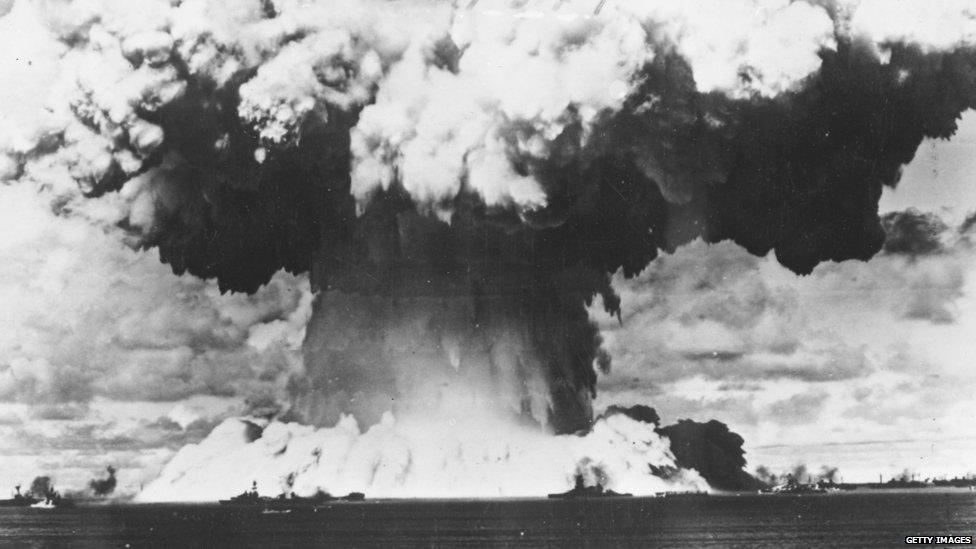

Then between 1946 and 1958 a new use was found for a series of coral islands surrounding a lagoon in the Pacific - Bikini Atoll became the site of 23 nuclear tests. A bomb detonated there was 1,000 times more powerful than the one dropped on Hiroshima. The islands remain uninhabitable today.

Nuclear explosion at Bikini Atoll, 1946

Now our view of coral reefs has evolved again and they have emerged as fragile, vulnerable places struggling to survive the onslaught of the 21st Century. Threatened by climate change, overfishing, ocean acidification, pollution and physical destruction, they are disappearing from the warm seas of the world.

And the prospect of losing them has inspired not only scientists to take action, but also artists.

Since 2006, huge sculptures, designed to give corals a new place to live, have been placed on the seabed off the coasts of Mexico, Grenada and the Bahamas.

One is of a group of bankers kneeling down, their briefcases by their sides and their heads buried in the sand. Another shows a man typing at a desk. A third is of a crowd of people of different ages standing close together with their eyes shut as though deep in thought or prayer. Then there is the figure of a young girl, arms outstretched, as though embracing the ocean. They are the work of 41-year-old artist and diver Jason deCaires Taylor.

Sculptures are usually unchanging - locked in stone, metal or wood - but these are unusual. They are designed to be colonised by sea creatures and as time passes their surfaces are becoming increasingly encrusted by shellfish and coral.

"The coral applies the paint, the fish supply the atmosphere and the water provides the mood," says Taylor. In years to come they will be engulfed by life in the sea, with just the vestige of the original form left. "The evolution of the sculptures is fundamental to their existence… It's creating its own form and own shape with just the silhouette of the human form remaining."

As a child, Taylor saw coral reefs in Thailand and Malaysia, but "many of these places now don't exist," he says. "And to see them diminish and disintegrate so rapidly is what's inspired me to take action."

Since Jason deCaires Taylor was born, in 1974, about one-quarter of coral reefs worldwide have been damaged beyond repair, and another two-thirds are under serious threat.

"By creating an artificial reef, not only would it provide a substrate for marine life it would also draw visitors away from natural reefs, which is an increasing problem in some parts of the world.

"I hope they'll eventually just disappear into the reef system," he says.

"Coral reefs are the first areas that our planet might lose in the next 50 years so I certainly want to bring more attention to them."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published14 July 2015

- Published7 July 2015

- Published30 June 2015

- Published23 June 2015

- Published16 June 2015

- Published9 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015