When concrete buildings drive people mad

- Published

Post-war architecture is loved by some and loathed by many. A series of battles is taking place across the UK over whether to preserve certain concrete buildings. Which ones have divided opinion the most?

The destruction of a historic building usually provokes strong reactions. This is especially true if it happens to be a building that was designed in the years after World War Two. Brutalist buildings in particular generate heated debate. The raw concrete creations from the architectural movement of the 1960s and 1970s often face the threat of demolition.

Admirers of post-war modernism have staged regular campaigns to get their favourite buildings listed before the wrecking balls arrive. But not all of them are successful. The Hyde Park Barracks is the latest to have its application rejected, external.

But even campaigners agree that not all of these buildings are worth saving. The question of which ones are worth the money to preserve can cause furious arguments. Here are 10 of them:

Hyde Park Barracks

The Hyde Park Barracks was designed to accommodate more than 270 horses, and many humans as well

"I did not want this to be a mimsy-pimsy building… It is for soldiers. On horses. In armour," wrote architect Sir Basil Spence, external in 1971. "Mimsy-Pimsy" is not a phrase often used to describe the barracks. The eight buildings include a 33-storey grey tower block on the edge of Hyde Park, right in the midst of some of the most expensive properties in London.

It was built to house the Household Cavalry Regiment and their 270 horses. Supporters say, external that the building is a "legacy of the confident and flamboyant 1960s". But others have long argued that it looks out of place. In a move that could be seen as a victory for its critics, its listing was refused. Developers are already circling. Some have even released their ideas, external of what a new building could look like.

"We live in a throwaway society where we buy stuff and if something goes wrong we chuck it away," says John Glenday of The Rubble Club, external, a society for architects who have seen their buildings destroyed in their lifetimes. "In terms of maintenance and upkeep, it's all too tempting just to detonate some TNT and remove the building completely."

Birmingham Central Library

The library was called a "concrete masterpiece"

Prince Charles described it as looking like a place "where books are incinerated, not kept". The old library was actually only opened in 1974 and was designed by Birmingham-born architect John Madin who died in 2012.

It had been called a "concrete masterpiece" and Historic England fought unsuccessfully to get it a Grade II listing. Campaigning group Friends of the Central Library also lost the battle to save it and it's in the process of being demolished. A new £189m library opened in the city's Centenary Square in September 2013.

There are those who argue that the current wave of demolition is putting a key part of history in danger. "We could lose that connection with how people viewed their future at the end of World War Two," says architectural historian Ellen Leslie. "There we were, in the 50s, 60s, and up to the end of the 70s, renewing ourselves after the war. And wanting to forget about the past and looking forward to the future."

"This was their way of reflecting their feelings," she adds.

Plymouth Civic Centre

The building was due to be demolished in order to save money

The centre is a sore point to many. The 15-storey building was opened by the Queen in 1962 and used to be the city's council offices. It was an important part of the plans to rebuild Plymouth from the rubble that World War Two left behind.

Historic EnglandEnglish Heritage have previously urged for the whole of Plymouth city centre to be protected. "The night of 21 March 1941 basically obliterated the entire centre of the town and what happened afterwards was actually pretty visionary," said the chief executive of Historic England Simon Thurley at the time.

But Plymouth City Council said that the Civic Centre had become too expensive to maintain. They added that the building was not fulfilling its purpose and that modernising it would cost millions.

It was due to be demolished but Historic England stepped in and it was granted listed status in 2007. It was sold to developers Urban Splash earlier this year. Their director, Nathan Cornish, said it was a unique building "set within the context of a famous post-war master plan".

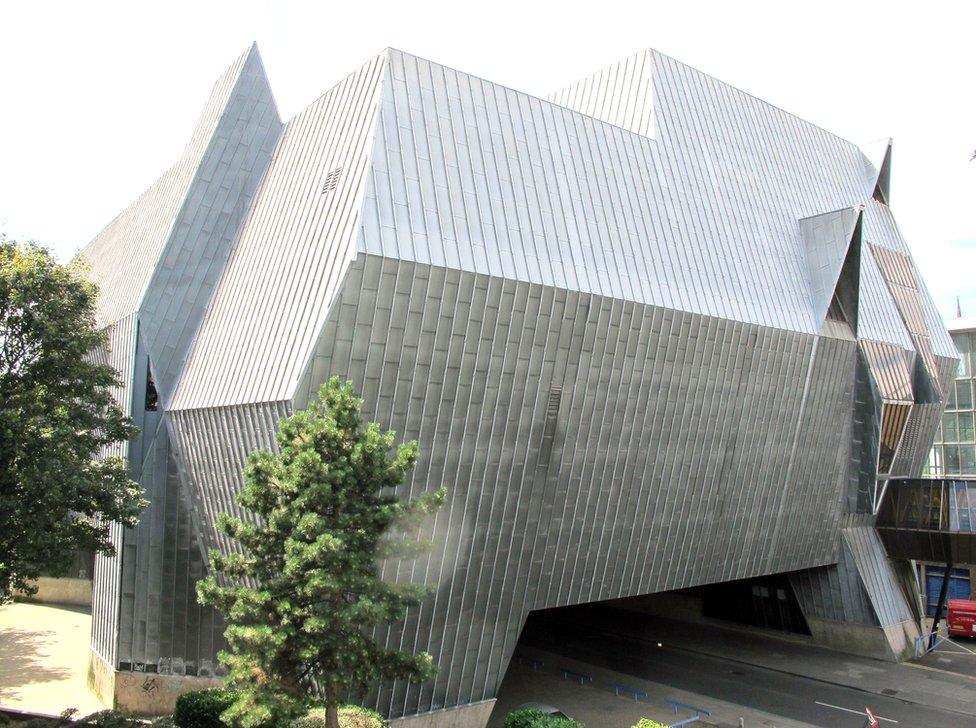

Coventry Sport Centre

The elephant-shaped building is facing demolition after a failed campaign to get it listed.

It was completed in 1976 and is linked to an earlier building which has been already been protected. Campaigners say that it's important to preserve as many landmarks in Coventry as possible because so many older buildings were razed to the ground during World War Two.

But it was decided that the building lacked "sufficient architectural merit", external. A £36.7m swimming pool and leisure centre is set to replace it.

Preston Bus station

The bus station was once voted the city's favourite building

Campaigners argued for years that the 1960s creation was "one of the most significant Brutalist buildings in the UK". It was once even voted as the city's favourite building, external.

Despite this, it took three attempts to get it listed and it only narrowly avoided demolition.

Its Grade II listing was "not the outcome we were hoping for", according to Preston City Council. They said it would cost more than £17m to modernise the station. But Historic England said that the "truly remarkable" building deserved protection.

Cumbernauld Town Centre

The shopping centre, built in the 1950s, was once voted as Britain's most hated building, external in a TV poll. The centre has been described as a "rabbit warren on stilts". It has also been awarded two Carbuncle honours , externalfor having Scotland's "most dismal" town centre.

But the mega structure was also listed as one of 60 key monuments, external of post-war buildings in Scotland. The shopping centre was expanded in 2007 and Cumbernauld won the Best Town at the Scottish Design Awards in 2012.

The Ulster Museum extension

The museum was first built in the 1920s and then expanded 40 years later

Francis Pym won a competition to extend the Belfast museum in the 1960s. The result was praised, external for its "barbaric power". But critics found it overbearing.

The argument continued in 2005 when a major refurbishment was announced. Some conservation groups expressed concern over the plans, external. The Ulster Heritage Society , externalwent as far as saying that a further glass extension would "seriously threaten [the building's] value".

But the refurbishment went ahead and the museum reopened on its 80th birthday, external.

Dudley Zoological Gardens

The zoo has the largest single collection of Tecton buildings, external in the world. These reinforced concrete pavilions were designed by The Tecton Group in the 1930s, led by renowned Russian architect Berthold Lubetkin. There are 12 in total including the Polar Bear Complex and the Tropical Birdhouse.

But the designs went out of fashion. Critics also began to raise animal welfare concerns over the enclosures. Most of the buildings were too small and heating them properly was difficult. Terraces had also been created so that people could look down onto the animals but it made many of them nervous.

Some of the buildings fell into neglect. Eventually, the zoo's architecture was declared an endangered heritage site and it was put on a list alongside Machu Picchu in Peru.

It prompted a massive renovation project. The Bear Ravine enclosure was rescued after £1.5m of repairs, external. The other buildings were integrated into the modern animal enclosures and put to new uses.

Northampton Greyfriars bus station

The bus station had problems with mineral stalactites growing inside

This 1970s building was once described as a "mouth of hell". It used to dominate the city's skyline and was meant to attract people to a nearby shopping centre.

Reaction to the station, external was said to be "mixed" after it opened. And the building was quickly plagued with problems, from mineral stalactites forming inside the building to raw sewage leaks.

The local council called it an expensive eyesore and had it demolished earlier this year. In about six seconds, more than 2,000 individual explosive charges reduced the building to 22,000 tonnes of rubble.

The Twentieth Century Society, which campaigns to protect post-war architecture, said that the demolition added to the myth that Brutalist buildings were monsters. But the council said that its removal would breathe new life into the area.

Sheffield's Park Hill

The building was nicknamed "San Quentin" after the US prison

The argument over whether these flats are a design icon or concrete eyesore has been going strong for decades. Its walkways were nicknamed "streets in the sky" and it was said to be one of the most ambitious inner-city developments, external of the 1960s.

But as the years passed, it fell into disrepair. It was eventually dubbed "San Quentin" by some of the locals, after the notorious US prison that was immortalised in a song by Johnny Cash.

Campaigners say that many of the concrete monoliths that sprung up after World War Two are being blamed for their neglect. "Often they've been maligned because of management and maintenance issues rather than because of faults in the actual design," says Henrietta Billings, senior conservation adviser at the Twentieth Century Society.

The whole thing was listed in the 1990s, external. Regeneration company Urban Splash took over its redevelopment in 2008. Phase one of the project was nominated for the Stirling Prize, the Royal Institute of British Architects' highest accolade.

But others have been less enthused. As former Liberal Democrat council leader Paul Scriven put it: "I'm still of the view that you can't polish a turd, to put it bluntly."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.