The downside of being a property guardian

- Published

A new sitcom centres on six young people living as property guardians in an abandoned hospital. The UK's housing crisis has driven people to unusual solutions and some think they're being exploited, writes Eleanor Ross.

The rocketing cost of rent in some parts of the UK is squeezing tenants so hard that property guardianship, or "legal squatting" as it has been dubbed, is the only way some can afford a roof over their heads.

Guardians pay to take "licence" of a room or space within a vacant building for less money than a private rental agreement - earning the owner of the building cash and keeping genuine squatters away. The practice now forms the backdrop to a Channel 4 sitcom, Crashing.

But low rents and a central location come with a catch.

The vacant buildings aren't always primarily residential. Guardians live in buildings including disused police stations, garages, office blocks and pubs. Fiona, a 25-year-old guardian from London who does not want to give her real name, has lived in four different properties in two-and-a-half years. Most had problems, but a particularly bad experience was in a former police station in Marylebone that had been sold on.

"Few people can say they've lived somewhere with a shooting range and a sports hall. Even so, the carpets were covered in raw sewage, there was poor lighting in the corridors, and flies in the showers. Perhaps it sounds minor, but these weren't cleaned for three months. The lighting was fixed a week before we moved out, and the flies? Well, we had to put up with those."

Another property that Fiona lived in was a former maternity retreat in central London. She describes it as by far the worst experience as a guardian, and an "exploitative" setup. As so many guardians wanted to transfer to this property, prices increased to £865pcm from the advertised £450pcm over just two days. There was no hot water, stuffy airless rooms with windows that didn't open, broken showers, and a faulty ventilation system.

As property guardian Matthew (again not his real name) discovered, buildings are required - according to some councils' guidelines - to provide running hot water alongside a toilet. "This was something I approached my company about but they showed no interest. Sooner or later I expect that somebody will realise how legally dubious this whole enterprise is and the companies will either have to become more accountable or the whole thing will come to a halt."

Another property Matthew was staying in had been squatted immediately before he turned up. "Nothing had been done to spruce the place up. The room I moved into was strewn with clothes and heroin paraphernalia and I had to clean it up alone."

Ed Moyse, who lived in an old pub as a property guardian

Ed Moyse, 26, lived as a guardian in London while he set up his business. For just £300 per month he lived in an old pub that had previously been a restaurant in central London. He had to put up with invasions of exceedingly large rats. "At the worst point, we'd come home after a night out, burst into the kitchen, and discover 10-15 rats scurrying away in different directions. I thought they were like big mice, but they're more like small dogs. We'd come down to the kitchen in the morning to discover clocks knocked from the walls and bottles smashed on the floor."

Property guardians don't have a lot of rights. Dr Sarah Keenan, from Birkbeck University's department of law, explains they are only licensees, not tenants. "Whereas a tenant has the right to exclude 'all the world' including the landlord, licensees have the lesser right of 'occupation', and are generally expected to allow the landlord access as and when he seeks it."

Keenan is also critical of the role property guardian companies are playing in the housing crisis. "Guardianship properties are highly exploitative of the housing crisis. The situation guardianship companies are setting up is one that profits from buildings being left undeveloped and all but uninhabitable for long periods, and from the increasingly desperate situation of people who are unable to afford market rent.

"It makes the crisis worse by normalising a situation in which landowners view their land as a purely financial asset rather than a limited and vital human resource, where non-owners live in squalid and potentially unsafe temporary accommodation."

It is argued that renting out non-residential buildings to guardians is legal, at least once planning permission for change of use has been granted. Because property guardians are on licence agreements and not tenancies, their primary role is to secure the building on a temporary basis.

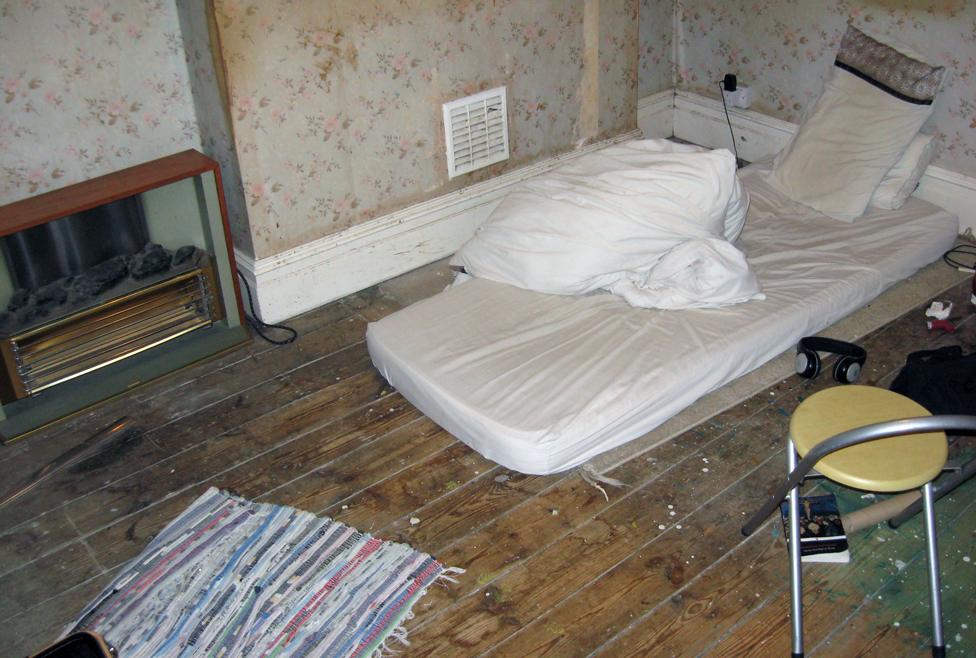

A property guardian's bedroom in a building in Catford

Katharine Hibbert, founder and director of Dotdotdot Property, a small guardianship company, agrees that more needs to be done about the housing crisis. "What we really need is to build more good homes. Property guardianship can never be the whole solution - it's not right for everyone. But getting Britain's empty properties into use can definitely do a lot to ease the current housing shortage, and we're glad to help our guardians find good homes they can afford in the most expensive parts of the country."

She emphasises that all the empty properties administered by Dotdotdot meet the same health, safety and fire standards as required for normal rental properties.

Another company, Guardians of London, says it installs temporary fixes to make its properties habitable for residents. "For a small start-up fee, we'll install 'wheel in, wheel out' shower pods so we can provide temporary washing facilities," explains Gavin Handman, head of operations. "The guardians provide their own kitchen facilities, including microwaves and portable kitchen hobs that are no greater than 13 amps for fire safety reasons.

"If it's a large building, we place guardians strategically throughout the building. If it's a big former office building, for example, we can put as many as 30 guardians in there if necessary, but we don't overfill our properties like some other guardian companies, so wear and tear is kept to a minimum."

However, Richard Harding, director of communications, policy, and campaigns at Shelter, thinks it's no wonder many are trying to find alternative solutions. "That people are resorting to the unstable, unsuitable and often unsafe option of property guardianship is yet another symptom of our chronic affordability crisis."

Guardians are aware of their lack of rights. Matthew describes the deal between company and guardian as "Faustian". He explains how guardians almost have to agree to having no rights. "Agreeing to live in one of these properties is not a rational decision but it is one made often by financial compulsion and not as the companies would like to have you believe, as an exhilarating bourgeois lifestyle choice."

There are certainly positive factors. Cheap rent and a central location are clearly the main draws, but guardians also cherish the community spirit that comes with living in a shared building. Although guardians can, in some properties, be given just 24 hours to vacate, Moyse thinks that the flexibility can be seen as a bonus of sorts: "One of the great things about being a property guardian - it's typically difficult to find rent in London for anything less than a year, but we could leave at a month's notice if we wanted."

Richard Blake, from Bristol, is mostly content with being a property guardian. "I'm not forced to see most of my wages go straight to rent and bills. I wouldn't be here after 18 months if the positives didn't outweigh the negatives and I don't think there is any other way that my girlfriend and I could get on the housing ladder while living in Bristol."

Fiona sees property guardianship as a lifestyle choice. "You have to be prepared to walk in and clean before you unpack, and a little DIY knowledge goes a long way. It's all about the community you create - when I lived in Hertford we played ball games in the garden, and when I lived in Chelsea we'd eat and drink together. With the bad comes the good."

Moyse agrees. Despite the rats, he found the people he moved in with were "great company". "It was one of the most interesting things I've ever done."

More from the Magazine

Why are so many British homes empty? (December 2015)

Peep show and the stigma of flat-sharing in your 40s (November 2015)

The last woman left on a derelict street (November 2015)

The lowest rung of the housing ladder? (October 2015)

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.