Afrofuturism: Why black science fiction 'can't be ignored'

- Published

Science fiction has long been criticised for its lack of racial diversity and inclusion.

It's rare to see a lead character who isn't white.

One study of the top 100 highest-grossing films in the US showed that just eight of those 100 movies had a non-white protagonist, as of 2014.

Six of those eight were Will Smith, according to diversity-focused book publisher Lee and Low Books.

The long-term exclusion of people of colour from science fiction offers up an interesting paradox.

How can a genre that imagines a future of infinite possibilities be seemingly unable to imagine a future where black people exist - or at least have any relevance?

Herein lies the power (and importance) of afrofuturism, and while you may not have heard of the term, there's a good chance you've been introduced to it already.

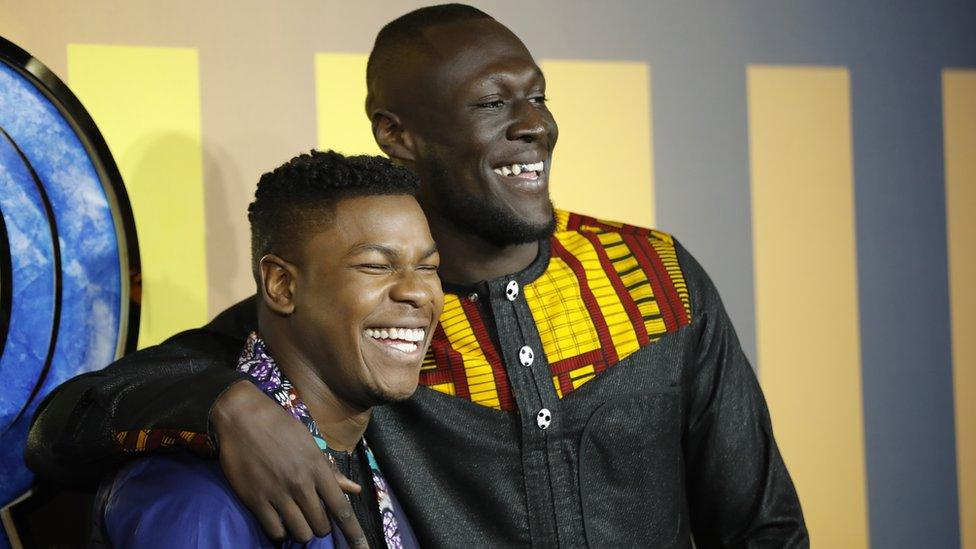

Lupita Nyong'o and Letitia Wright in Black Panther

Janelle Monáe and Dirty Computer: An Emotion Picture

Allow Instagram content?

This article contains content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Instagram cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Afrofuturism is perhaps best summed up by the queen of contemporary afrofuturism herself — Janelle Monae.

Her futuristic music videos and radical aesthetic (she even calls her fans "fAndroids") are seen by some as a key force for pushing afrofuturism into the mainstream.

"Afrofuturism is me, us... is black people seeing ourselves in the future," she explains, external in a 30-second video clip for Spotify.

It is no surprise then that Janelle cites the movement as the inspiration for her new narrative film, Dirty Computer: Emotion Picture, a visual accompaniment to her latest album (which is currently trending on YouTube).

Janelle Monae promotes Dirty Computer in New York City

"I was writing this music that was really inspired by science fiction and afrofuturism," she told BBC Radio 1 in March.

"Telling these stories through the lens of a young black woman and speaking of a future where we're included, we're not the minority, but we're the heroines, we're the leaders, we're the heroes... I felt like I had a responsibility to [do] that."

The 44-minute film, starring and produced by Janelle, tells the story of Jane 57821, a woman who's on the run from a totalitarian government that seeks to scrape her memories.

The film features minority groups who are under threat - including people of colour and LGBTQ individuals.

Co-director of Dirty Computer Andrew Donoho told Newsbeat that viewers can expect to see a film that pulls inspiration from a long list of sci-films through the lens of afrofuturism.

"The entire project was about exploring the sci-fi landscape that we all knew and loved so much, while injecting Jane's commentary about race, sexuality, and the future of black culture.

"We wanted a true sci-film that properly represented the black and LGBTQ community in a way that was honest - something rare in Hollywood," he added.

'Black to the Future'

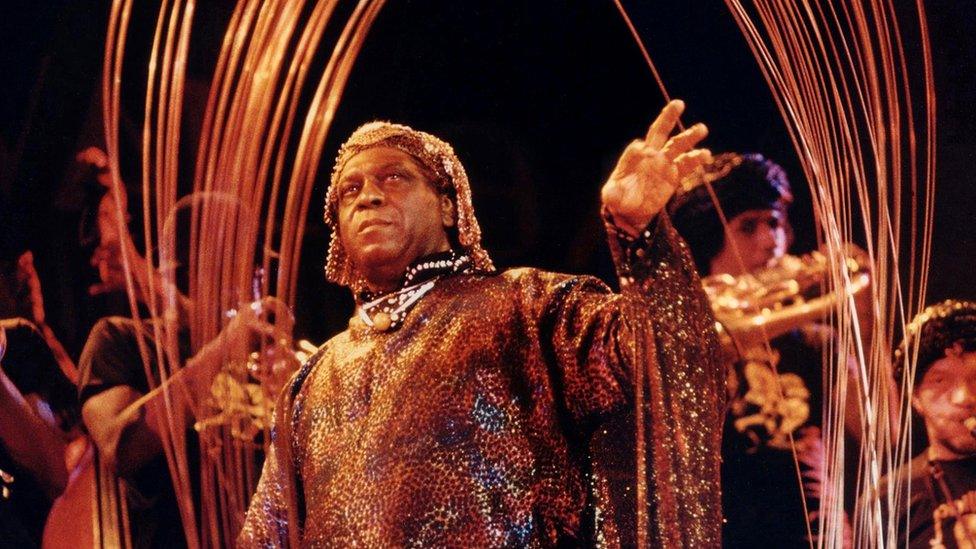

Solange Knowles performs with The Sun Ra Arkestra

The term "afrofuturism" was originally coined and defined by cultural critic Mark Derry in a 1993 essay entitled "Black to the Future", although the idea has existed for much longer.

Missy Elliott, Janet Jackson, TLC, and Solange Knowles have all been credited with exploring the movement, but one of its most famous contributors to the genre is the musician and poet Sun Ra.

Regarded as a pioneer of afrofuturism with more than 1,000 recorded songs spanning more than 100 albums, he is particularly well-known for telling his own fictional origin story - that he was an alien who'd come to Earth from Saturn, sent on a mission to preach peace and speak through music.

During his career, Sun Ra and his band (the Arkestra) went on a 25-year-long tour performing and selling their music. The band continues to perform following the death of Sun Ra in 1993.

Sun Ra is considered a pioneer of the genre

Aside from music and film however, afrofuturism also incorporates literature and art, combining them with science fiction, history, and fantasy.

Afrofuturism can be split two simple questions: "Who are we?" and "What is true about the world?" according to Steven Barnes, a professional science fiction writer and lecturer on the topic.

"It is just our perspective on the question of how did we get here, what's going on, and what's the future going to be like? Which are the basic questions that you find answered through science fiction.

"Afrofuturism, then, would be the science fiction, fantasy and horror created by or featuring the children of the African diaspora (people of African origin living outside of the continent)."

Movement to mainstream and Black Panther

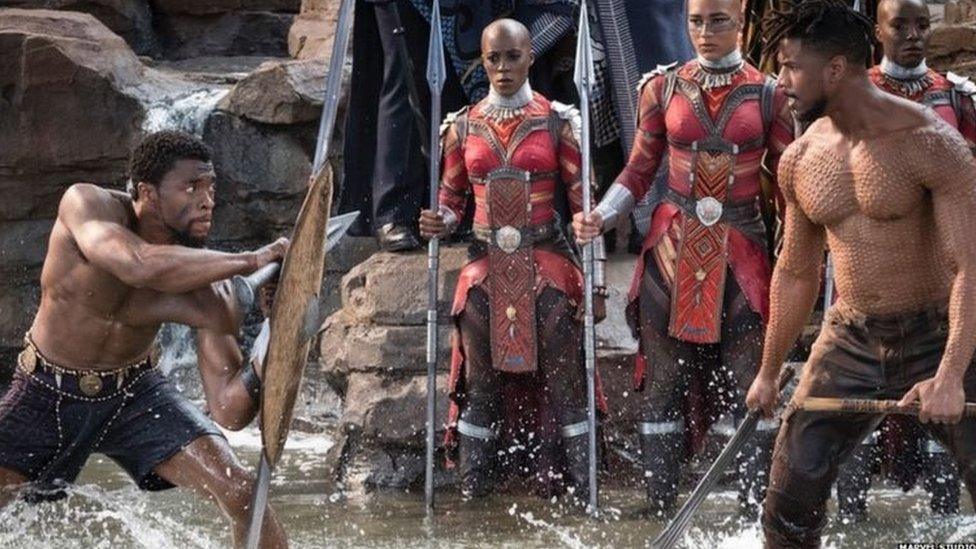

Chadwick Boseman prepares to battle Michael B. Jordan for the throne of Wakanda in Black Panther

Afrofuturism has more recently soared to commercial success with the release and critical acclaim of Black Panther.

The blockbuster movie broke several records, including highest-grossing film of 2018, third-highest-grossing film in the United States, and 10th-highest-grossing film of all time. It features an afrofuturistic superhero in a world where black people have the most advanced technology on Earth.

"That is afrofuturism at its best," Steven told Newsbeat.

"You have something that deals with our past, our future, our present, our spirituality, our ability to love, to wield power, connections to family and language, and on and on and on and on."

"This is what I've been waiting for since I was child," he added.

Contrary to science fiction's predominantly white history, the depiction of Black Panther on screen seems to have been exactly what the rest of the world had been waiting for too.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

As the highest-grossing movie directed by a black filmmaker in North America, Black Panther's success (and 96% rating on Rotten Tomatoes) is indicative of a wider point about afrofuturism's appeal, and the desire for these stories to be told more broadly.

In March, Black Panther became the most tweeted about movie, external of all time, according to Twitter Movies.

So why is afrofuturism important?

The genre's importance in part comes from its ability to connect people of African descent not only to their origins, but to each other.

King Britt, a composer, producer and DJ, had been working on music before the term afrofuturism existed - but upon its conception he was surprised to find other people just like him.

Composer, DJ and producer King Britt

"When the term and movement came to light, I was like, 'Oh wow, there are other black nerd kids like me who like sci-fi and want to change the future to include us more'.

"It was a form of escapism to think this way," he added.

Steven Barnes, who teaches the subject, argues that afrofuturism's necessity comes from science fiction's history of excluding black people.

"You could have a movie where worlds collide and they build spaceships to save the world... and all the people on the spaceships are white," he told Newsbeat.

Science fiction writer Steven Barnes is a lecturer on afrofuturism

"The filmmakers didn't even question this, we literally don't exist in their fantasies. Now the situation is a lot better in a lot of ways."

Afrofuturism may not be able to rectify an entire history of exclusion, but its impact, born of its attempts to answer important questions, is something that can't be ignored.

"This is why we're having this conversation," Steven said.

"The world is actually interested in the question."

Follow Newsbeat on Instagram, external, Facebook, external and Twitter, external.

Listen to Newsbeat live at 12:45 and 17:45 every weekday on BBC Radio 1 and 1Xtra - if you miss us you can listen back here.

- Published11 February 2018

- Published13 February 2018

- Published9 February 2018

- Published11 March 2018

- Published21 February 2018

- Published9 February 2018