SLS: The rocket in need of a destination

- Published

- comments

SLS leans on its shuttle heritage

Nasa has finally delivered its design for a huge rocket that could take humans to asteroids, Mars and a few other exotic corners of the Solar System.

The Space Launch System, external (the name will be changed at some point, surely) will be the most powerful launcher ever built - more powerful even than the Saturn V rockets, external that put men on the Moon.

In its full-up configuration the SLS will be some 12m taller than the moonshot rockets and have 20% more thrust as they clear the pad.

The SLS, depending on just how big the final vehicle becomes, could be carrying to low-Earth orbit some five-to-eight-times the payload mass of a single Ariane 5 rocket, external, one of the most muscular rockets in operation today. That is astonishing.

But then, if you want to go to Mars, land, and get home - you will need an awful lot of equipment, and possibly even more than can be carried on one SLS.

To keep development costs as low as possible, the new rocket will draw heavily on shuttle heritage and the research work done under the now defunct back-to-the-Moon Constellation programme, external that Congress and President Obama killed last year.

The core and upper stages are the same width as the shuttle's iconic orange external tank - 8.4m. The shuttle orbiter's main engines will also be pressed into service anew on the bottom of the new core stage, and the solid-fuelled boosters that used to power the shuttle off the pad will now perform the same function for the SLS (although in the stretched version that was already being prepared under Constellation).

Infrastructure and tooling that looked bound for the scrap heap after the retirement of the shuttle suddenly has a new lease of life.

But even with this back-to-the-future approach, the SLS will be an immense financial undertaking, and there are sure to be many people who will baulk at the cost of it all.

Nasa calculates it will have spent about $18bn on the project by the time the inaugural (unmanned) test launch occurs in late 2017. This figure includes not just the work on the rocket, but its Orion astronaut capsule and the ground work needed at Kennedy to get the spaceport ready for a new type of launch vehicle.

It should be noted also that the 2017 maiden test flight will use a "lite" variant, one capable of lifting about 70 tonnes to low-Earth orbit. Further work and expenditure will be required to develop a rocket capable of lifting more than 130 tonnes - the spec demanded by Congress.

So that $18bn is actually a figure for one point along a development road. The final cost for SLS has been estimated by some to be more than $30bn.

What will be interesting to see now is whether Congress, having made such a fuss about the need for this rocket, will stay the course and continue to fund it as federal funds get squeezed on all sides.

Nasa's budget for the next few years will be flat, at best. It is also grappling with a big cost overrun on another of its top priorities - the James Webb Space Telescope - and for which the shortfall will have to be picked up by programmes across the agency, perhaps even human spaceflight.

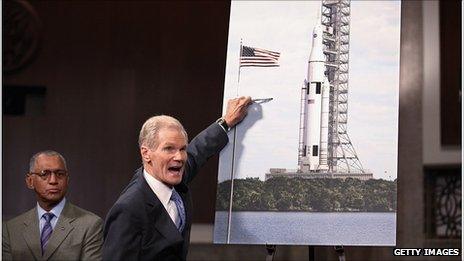

Senator Bill Nelson, a Florida Democrat and former astronaut, was one of the key people on Capitol Hill who helped shape the idea for the SLS. He knows the arguments for the rocket will have to be repeated often and loudly if the vehicle is to avoid becoming another of those Nasa projects that is underfunded and ripe for termination when the political winds in Washington change direction.

"Will it be tough times going forward? Of course it is," Mr Nelson told journalists. "We are in an era in which we have to do more with less - all across the board - and the competition for the available dollars will be fierce."

Senator Bill Nelson will have to work hard to keep Congress true to the vision

Nasa will also have to work harder to explain to people what this rocket is for.

Science and space reporters like myself have no problem fantasising about the missions and destinations made possible by this "monster", as Senator Nelson called it. I drool at the thought of the huge telescope we could put in orbit with the SLS, or the scale of the spacecraft it could send to the outer planets.

But what about the ordinary person, the everyday American taxpayer who may be unfamiliar with space matters?

The genius of JFK and Apollo was the simplicity of the message - of "achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon".

The "destination" came first - only later did the American people understand "how" it would be achieved.

With SLS, American taxpayers have been given the "how" first with a rather vague promise of "where" at some future date. An asteroid in the 2025 time frame has been mentioned, but beyond that very little has been clarified.

One senior Nasa official said on Wednesday that the SLS had been designed in a "capability-driven framework".

Had Kennedy said "our goal is to develop capabilities to the point where hopefully in a few years we can think about sending people to an asteroid and later to Mars" - how long would the dream have stayed alive?