Global fallout: Did Fukushima scupper nuclear power?

- Published

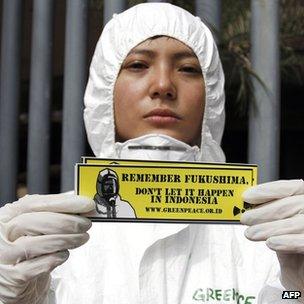

Fukushima sparked anti-nuclear sentiment in many countries, though not in all

In the tense days nearly a year ago when smoke rose around the stricken Fukushima Daiichi power station as if from a battlefield, when hydrogen explosions tore the reactor buildings apart and workers fought for their lives and Japan's future, it seemed as though we might be watching the death throes of the nuclear dream.

In the wake of what is officially classified as one of the two worst nuclear accidents in history, ranking at Category Seven on the International Event Scale (INES), the "electricity too cheap to meter" vision of the 1950s appeared to be turning into a technology too costly to contemplate in terms of the human and financial balance-sheets.

Within weeks, Germany announced it would close all its nuclear reactors, and Switzerland followed suit. Even China, busiest of the new builders, delayed approval for new power stations.

And around the world, opinion poll after opinion poll showed nuclear power losing its lustre.

"Fukushima impacted significantly, firstly on public opinion, and secondly by creating the need to analyse what happened from a technical point of view, to learn lessons and apply them," says Luis Echavarri, director-general of the ONuclear Energy Agency (NEA), external of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

"I see a clear impact on plans for the future in the sense that there is a certain delay in taking decisions on new power plants - I think that's going to last for three to four years."

Fissioned view

The vast majority of the reactors operating before Fukushima are still operating; even Germany stopped short of shutting them all down.

The glaring exception is in Japan itself, where only two out of 54 reactors are currently in operation. Some are shut for good; with others, local authorities have yet to decide whether to permit a restart.

But outside Japan, how does the future look a year on? Will Fukushima mark a full stop or just a comma in the nuclear story?

As always with this issue, the same set of facts produces very different interpretations.

John Ritch, director-general of the industry-backed World Nuclear Association (WNA), external, believes it has created a small pause - nothing more.

"Fukushima was a setback in terms of public perception and increased timidity on the part of policymakers," he says.

"But we're quite confident that the underlying facts remain the same; and that's what's caused dozens of governments to review their policies for the 21st Century and decide to make nuclear energy a central part."

Many parts of the Fukushima site are still off limit to people, with robots the only exploration tool

Central to those "underlying facts" is the need for rapid decarbonisation of global energy to avert dangerous climate change.

Germany, he asserts, will come to rue its decision to pursue that goal through renewables alone.

Tom Burke, founding director of the sustainable development thinktank E3G, external and a long-time opponent of the nuclear industry, has a very different take.

"What I think will be even more significant [than German-style closures] in the long term is the economic impact," he says.

"The economics of nuclear have always been bad; and because countries such as Japan and Germany in particular are going to drive even harder into renewables, costs are going to come down even faster than they have, making nuclear even less cost-effective."

He also cites blockages in the supply chain, skills shortages and escalating concerns over Iran's possible military intentions as factors set to take nuclear out of the equation.

Asian century

One thing is clear: even before Fukushima, the real centre of nuclear power was shifting from its traditional heavy users such as France and the US to Asia.

South Korea has emerged as a major user of nuclear electricity and an exporter of technology; but China is the really big player.

Of about 60 reactors under construction around the world, 26 are in China, with many more set to follow.

There are observers who quietly applaud China for its apparent capacity to build reactors on time and on budget, while European projects at Flamanville in France and Olkiluoto in Finland flounder, external in a miasma of escalating costs and stretched deadlines.

Tom Burke is not among them. He points to the low building standards that contributed to the heavy death toll from the 2008 Sichuan earthquake and the recent health scare over melamine in milk products as evidence that China struggles with quality control - a key issue in building reliable nuclear reactors.

"How China is possibly going to create quality control mechanisms of a standard that exceed the Finns or the French is beyond me," he says.

"So what you're basically doing if you're in a country such as the UK is you're putting your future carbon policy in the hands of Chinese quality control inspectors, because if China drops another Category Seven incident, nobody's going to be able to run reactors."

Clunkers, not cash

The UK and many other countries are - at least on paper - pushing ahead with plans to build new reactors as part of a package aimed at curbing global warming and increasing their energy security.

However, a new trend has emerged in the last six months or so, with France - the biggest nuclear nation in Europe - announcing plans, external to extend the lives of existing reactors rather than build a big fleet of new ones.

In the US, licences for two new reactors were granted, external in February, the first since 1978 - underwritten by a vast $8bn (£5.1bn) in loan guarantees from the public purse. But the new build number is dwarfed by the 60-odd old ones that have been granted 20-year stays of execution.

This is bound to have an impact on other countries' programmes. If fewer reactors are being built, there is much less experience from which to learn; less learning makes it harder to build them quickly and cheaply.

With France, for example, constraining its building programme, will that increase costs for the UK?

You can also argue that on safety grounds, this is the wrong strategy: if new designs are safer than old ones, as their publicity would have us believe they are, would not the safest thing be to replace old with new - a kind of nuclear "cash for clunkers"?

Here, the industry gives conflicting messages. During the WNA's news briefing for reporters prior to the Fukushima anniversary, one official listed the increasing safety features of new reactor designs, while another described them as partly "marketing spin".

For John Ritch, the supposedly enhanced safety features of the so-called Generation 3+ reactors coming on to the market, such as the Westinghouse AP-1000 or Areva's EPR, are not really relevant to Fukushima.

"What Fukushima really represented was a failure of imagination," he says.

Nuclear power has not achieved the status dreamed of in its very early days

"You didn't need to tear the station down and build it again with AP-1000s - what you needed to do was spend a few million dollars on sea defences.

"If you live in Japan, you have to anticipate a tsunami, and they didn't do a good job of thinking through the threat - a major requirement is to have backup cooling and they didn't do that; they failed to capture it for years and years."

WNA says that regulators and operators have learned the lessons of Fukushima by putting their reactor fleets through safety reviews and "stress tests".

The processes ask whether there are risks that have not been imagined possible that now have to be considered - both natural risks, like floods, or of human agency.

It asks whether an electricity supply can be maintained in the event of a complex sequence of failures, and whether staff are sufficiently trained to deal with an event of Fukushima-like magnitude.

US stress tests have thrown up issues that are being addressed by spending about $100m across the country - roughly $1m for each reactor.

On the new vs old argument, Mr Ritch uses a car analogy: new cars might be safer than old, but still your old one might be safe enough, and economics might dictate that you do not change it.

Whether the analogy works for people living around the controversial Fessenheim station on the Franco-German border, built on a geological fault line, or near the Vermont Yankee station in the eastern US where maintenance standards were low enough to allow a cooling tower to collapse, external in 2007, I am not so sure.

Nevertheless, the new designs are beginning to be built, in China as well as France and Finland, and maybe the UK. WNA believes other developing countries are set to join the nuclear club, with Vietnam likely to open its first reactor by 2018 and Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia not far behind.

All have experienced tsunamis in recent years, and how the public would react to the laying of the foundations is unknown.

Long future

The Fukushima accident can be traced back to a number of very different factors, depending on how you do your analysis.

Among them is the type of reactor used, a boiling water reactor. Steam pressure generated by excess heat and a reliance on pumps for cooling were among the facets of the design that created the sequence of events we saw.

So has Fukushima accelerated development of the so-called Generation 4 designs, some radically different from anything on the market now and potentially much safer?

The OECD's NEA funds part of the Generation 4 initiative, external, but Luis Echavarri does not see deployment any time soon.

"My view is that Generation 4 reactors need to be based on recovering credibility with public opinion first, so Gen 3 and 3+ have to be successful first," he says.

"Gen 4 do have the objective of being safer, but there are other criteria too: more economic, less waste, reduced proliferation risk - that's the combination that will make them attractive, but they need 20-30 years to be in the marketplace.

"And if they are to be in the marketplace in 20-30 years' time, then we first need to recover the credibility damaged by Fukushima."

The implication is clear: if the credibility damaged by Fukushima is not recovered, neither will the nuclear industry.

Some of the key things likely to determine whether credibility is restored include building new reactors on time and to budget, effectively cleaning up the Fukushima site and ideally allowing many of the displaced to return home, and developing robust long-term storage for waste.

And above all - no more accidents.

Follow Richard on Twitter, external

- Published6 March 2012

- Published5 March 2012

- Published19 July 2011

- Published11 July 2011