Bloodhound diary: Cockpit-centred view

- Published

A British team is developing a car that will capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h).

Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, theBloodhound SSC (SuperSonic Car), externalvehicle will mount an assault on the land speed record.

Wing Commander Green is writing a diary for the BBC News website about his experiences working on the Bloodhound project and the team's efforts to inspire national interest in science and engineering.

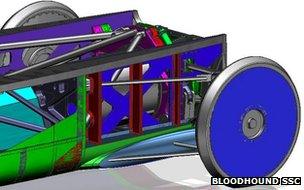

There is a subtle but distinct shift in the language of our engineering design team. Previous design meetings talked about the big concepts - aerodynamic stability and the shape of the bodywork, design options for 1,000mph wheels, fuel supply requirements for the EJ200 jet engine, and so on.

Suddenly, with the chassis in manufacture and more parts being made every week, the talk is of detail - refining the location of access hatches, delivery dates for the wheels, and the imminent start of the UK rocket testing phase.

We're even arranging the terms of the insurance for the car to run in the UK and in South Africa. Insurance for a 1,000mph car? Yes, really!

Of course there are still many design details to fix.

For instance, now that we have a much more accurate mass for the car (closer to six tonnes than five) the loads on our 1,000mph wheel bearings have gone up.

Bearing supplier Timken has re-calculated the life of the bearings with these new figures - and not surprisingly, it's gone down.

The good news is that it's still estimated to be around 50 hours, which is about 50 times more life than the car will need.

Long-life wheel bearings

A safety margin of 5000% works for me - but on the assumption that you can never have too much for safety-critical items, we're looking at squeezing a third wheel bearing in alongside the current two per wheel, just in case.

A simple change like this could save us having to change the wheel bearings at some stage - so it's worth a bit of effort now.

With parts now flowing into the Bloodhound Technology Centre in Bristol, we've had to introduce a strict stock control regime and a dedicated software programme called "Factory Master".

This does two things: it lets us know exactly where all the manufactured parts (of which there will soon be thousands) are at any moment - and it also stops the engineering team from nicking the best bits to use as paperweights!

As the public interest in the car continues to grow, Bloodhound trucker Graham Lockwoods pretty much has one of his articulated lorries tied up full-time moving our show car, jet engine, etc., around the country to shows and events.

Thanks to Rossetts Commercials, Graham now has a new Bloodhound truck dedicated to the task - and I'm sure we'll keep it busy over the next year or two.

Unfortunately, our full-size show car sustained a small amount of damage to one of the fibreglass wheel fairings recently - which ITV insisted on showing, despite Graham's requests not to.

Trucking in style

I'm delighted to report thatGraham got his own back, external, by telling the ITV team (on camera) that the damage was done late at night while backing the Bloodhound show car (which has fibreglass wheels and no engines) down a narrow lane near the venue - and they believed him.

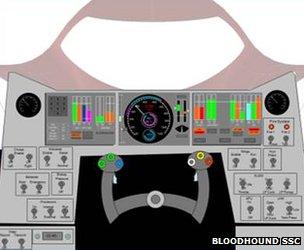

As we start to think about running the car next year, I'm putting some more thought into the cockpit design.

We are going for a "cockpit-centred" car, which means that almost everything can be controlled by me as the driver.

I'm not planning to control everything - I've already got plenty to do in a 10-mile run lasting 100 seconds - but the ability to select different configurations for individual test runs gives us a lot of flexibility whilst we test the car, rocket systems, jet engine, hydraulics, etc next year.

As part of the cockpit development, we've been offered an independent analysis of the cockpit design, to see if it can be optimised.

1,000mph office - work in progress

This will also allow us to publish a proper scientific explanation of the cockpit instruments (as opposed to my made-up reasons for why I designed it like that), as part of ourBloodhound Education Programme, external.

More details on my office layout to follow soon.

As part of the education programme, we ran a national schools competition last year with the schools winning the option for me to go and spend a morning with them, to tell the school about the car and to let their science classes interview me about the bits of Bloodhound that interest them.

One of the winning schools was Joy Lane Primary and I went there recently.

What a remarkable bunch of kids - and what a remarkable effect that Bloodhound is having.

One of their science group videos featured an eight-year-old holding a balloon, just before he let it go to rush across the room, and describing Newton's Third Law of Motion - which is the technical explanation for how the escaping air pushes the balloon along.

Bloodhound Education in Action

This just astonished me - when I was eight, I'd never even heard of Newton.

We've got almost 5,000 schools and colleges signed up to our education programme now and, based on this school, it's really working.

One of the difficult things to explain is Bloodhound's extraordinary performance - 0-1,000-0 mph, covering 10 miles of Hakskeen Pan, in around 100 seconds.

Ron Ayers describes the theory very well inBloodhound TV Episode 6, external, but that still leaves the question of "what does that muchgfeel like?"

As a Royal Air Force fighter pilot, I've experienced much higherglevels in jet fighters, but it's rather different in a car - long straight line 2gacceleration, then a sudden and fairly violent reversal to a 3gdeceleration (that's 60mph per second - imagine trying to stop a normal car from 60 mph in one second and you'll see why that's quite a lot).

To try and explain the sensations, I took Dallas Campbell (BBC's Bang Goes the Theory) and got him to do the narration for a 1,000mph run, whilst I subjected him to the appropriate levels ofg.

How did he do? You'll have to watch the programme on 30 April - but he didn't pass out, which is better than some journalists I know.

This won't hurt.... much

Another education theme I'm keen to develop is the science of dry lake beds - why are there so few perfect surfaces likeHakskeen Pan in South Africa, external- and how did Hakskeen come to exist in the first place?

Pans like Hakskeen tend to form from the erosion of soft rock, which provides the mud and silt for the perfect racing surface.

It's quite possible that this particular Pan is only 10,000-20,000 years old - only just born in geological terms.

The huge number of pebbles and rocks scattered across the surface (which the Northern Cape team have mostly cleared now) have been around for a while longer though - 300 million years ago, the whole Kalahari region of South Africa was near the south pole!

Along with the history of the Pan (which helps us to understand how the surface was formed, and how Bloodhound's wheels are likely behave at 1,000mph) I'm keen to understand the local weather patterns in more detail.

We have a weather station that will give us invaluable information

For instance, if the wind gets too strong we can't run - so if the wind gets up every afternoon, for instance, then we can plan to run in the mornings.

The Met Office has kindly agreed to help with this scientific monitoring, along with aCornwall College team, externalwhich is testing the equipment for us before we ship it to South Africa.

Live weather data from the world's best racetrack to follow soon.

- Published24 February 2012

- Published20 January 2012

- Published19 December 2011

- Published11 November 2011

- Published10 September 2011

- Published18 May 2011

- Published26 April 2011

- Published5 March 2011

- Published7 February 2011

- Published21 November 2010

- Published13 November 2010