EU space code of conduct: The solution to space debris?

- Published

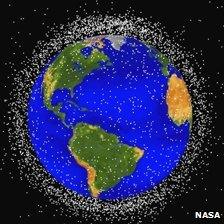

Space debris is likely to become a major issue in the years ahead

Hurtling through space at 27,000km/h (17,000mph), man-made space junk could potentially cripple financial markets, mobile phone networks and television signals if it crashed into satellites.

What might appear from Earth when we look into the night sky to be a peaceful, unpolluted realm of the unknown is described by the US Department of Defense as "congested, contested, and competitive".

Having some rules to stop the creation of more debris would seem to be in every space-faring country's interest, but so far the European Union's attempts to draw up a space code of conduct has hit a roadblock.

Experts say that's because of longstanding mistrust between nations, concerns because the agreement wouldn't be legally binding, and accusations that the code of conduct is actually just an attempt to prevent a space arms race.

'Future battlefield'

US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's recent announcement that her country would help the EU draft a code of conduct has been met with disapproval by some in the US, fearful that restrictions - including the disclosure of satellite locations and a promise not to attack other countries' satellites with missiles - could threaten its national security.

Experts say China and India were angry at not having been consulted early on, and both - like Russia - have not signed up to the code of conduct so far.

The fact that it's called the EU Space Code of Conduct, instead of the International Space Code of Conduct, even seems to be a reason some countries aren't keen to sign on, experts say.

"You have a situation where many nations are going to be more dependent on space, where many militaries are getting more dependent on space and as a result you have a situation where space is trending towards being a key battlefield of the future," said Dean Cheng, a research fellow at the conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation.

Dr Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, from the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi, agreed: "Space is the next big battle ground of the future. Outer space and cyberspace will constitute the arena of future warfare, given the increasing dependence of major powers on these two domains."

'No control'

Indeed, the more suspicious nations are unlikely to agree to certain obligations in the EU's 2010 draft code of conduct, including making available "information on national space policies and strategies, including basic objectives for security and defence-related activities".

Mr Cheng said he was sceptical that a non-binding code of conduct would stop countries behaving how they want in space.

"It's purely voluntary and there are no consequences for signing up to it and then breaking it," he said. "What you wind up with is a situation where those who are unlikely to generate debris... have no control over those who are bad citizens."

Others disagree, including Brian Weeden from the Washington-based think tank Secure World Foundation.

"There's plenty of things that we do where people have behaviour that they follow without an overriding punishment or legally binding mechanism," he said. "I think the real value is having a dialogue between all these different countries - that's something that's not really happened before."

Chinese missile test

According to the US space agency (Nasa), there are more than 21,000 pieces of orbital debris larger than 10cm in diameter, and half a million more between 1cm and 10cm. They stay in orbit for years and often decades before falling to Earth.

Prior to 2007, the bulk of space debris was made up of parts of old rockets. But in 2007, China fired a missile at a weather satellite, which created more than 150,000 pieces of space junk larger than 1cm. It's the kind of behaviour that the code of conduct would try to prevent.

"This is an attempt to stigmatise debris-creating activity, whether it's accidental or on purpose, as being internationally unacceptable," said Dr John Logsdon, a professor specialising in space policy at George Washington University.

A missile test by China in 2007 created 150,000 pieces of new debris

"That's clearly a motivation, to influence states to not do something like the Chinese test," he added.

China's missile test and a 2009 collision between a defunct Russian satellite and a US communication satellite together represent a third of all orbital debris, including much of the large debris, according to Nasa.

"If you're concerned about preventing collisions in space, that's where secrecy gets you in trouble," Mr Weeden said. "If you're keeping the location of your satellite secret, you are inherently taking on the responsibility to not let it hit anything, and not all those countries making that stuff secret have that capability."

'Noble' motives

Countries' objections about making the location of secret military surveillance satellites publicly available are "folly", Mr Weeden said.

"Everyone knows about it anyway," he said. "There are all these amateur trackers, these scientific observatories. All these other countries they don't want seeing the satellites - most of them probably know where they are, anyway."

The UK Defence Committee recently released a report saying the UK is vulnerable to nuclear weapons fired from space.

And in January, the Minister for Defence Equipment, Support and Technology, Peter Luff, visited RAF Fylingdales in Yorkshire to discuss drafting a national space security policy with the Minister for Universities and Science, David Willetts.

"Everyone is benefiting if we share information, because everyone's going to suffer if we don't," the UK Space Agency's chief engineer, Prof Richard Crowther, said.

"There's no way you can be operating in space and not suffer the consequences of things like space debris.

"Space is everywhere. It's hardwired into everything we do - as it is for all developed nations, so therefore you can't really have a conflict in space which is very localised," Prof Crowther added. "It will, by its very nature, become a global problem."

Despite the diplomatic posturing, mistrust and wariness about the code of conduct among some nations, Dr Logsdon said the EU's motives were honourable.

"Space is becoming a very busy place and without some agreed-upon rules of behaviour, it will be hard for everybody to operate safely in that environment.

"So I think the basic motivation underpinning the code is a noble and perfectly reasonable one."

- Published21 February 2012

- Published2 September 2011

- Published9 August 2011