Nasa's Curiosity rover edges closer to Mars

- Published

Communications from the rover during descent will come to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

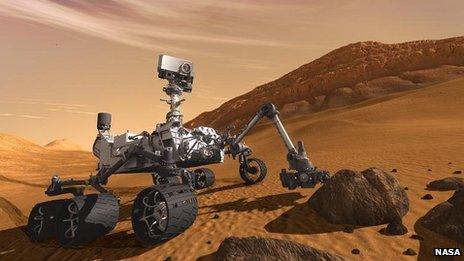

Nasa's Curiosity rover is on course to land on Mars on Monday, where it will search for clues in the Red Planet's rocks and soil about whether it could once have supported life.

The robot's flight trajectory is so good engineers cancelled the latest course correction they had planned.

To land in the right place, it must hit a box at the top of the atmosphere that measures just 3km by 12km.

Curiosity has spent eight months travelling from Earth to Mars.

The robot - -also known as the Mars Science Laboratory, external - has covered more than 560 million km.

"Our inbound trajectory is right down the pipe," said Arthur Amador, Curiosity's mission manager.

"The team is confident and thrilled to finally be arriving at Mars, and we're reminding ourselves to breathe every so often. We're ready to go."

The rover's power and communications systems are in excellent shape.

The one major task left for the mission team is to prime the back-up computer that will take command if the main unit fails during the entry, descent and landing (EDL) manoeuvres.

The robot was approaching Mars at about 13,000km/h on Saturday. By the time the spacecraft hits the top of Mars' atmosphere, about seven minutes before touch-down, gravity will have accelerated it to about 21,000km/h.

The vehicle is being aimed at Gale Crater, a deep depression just south of the planet's equator.

It is equipped with the most sophisticated science payload ever sent to another world.

Its mission, when it gets on the ground, is to characterise the geology in Gale and examine its rocks for signs that ancient environments on Mars could have supported microbial life.

Touch-down is expected at 05:31 GMT (06:31 BST) Monday 6 August; 22:31 PDT, Sunday 5 August.

It is a fully automated procedure. Nasa will be following the descent here at mission control at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

The rover will broadcast X-band and UHF signals on its way down to the surface.

These will be picked up by a mix of satellites at Mars and radio antennas on Earth.

The key communication route will be through the Odyssey orbiter. It alone will see the rover all the way to the ground and have the ability to relay UHF telemetry straight to Earth.

And mission team members remain hopeful that this data will also include some images that Curiosity plans to take of itself just minutes after touching the ground.

Allen Chen - the 'voice' of the Curiosity Mars rover landing

These would be low-resolution, wide-angle, black and white images of the rear wheels.

They may not be great to look at, but the pictures will give engineers important information about the exact nature of the terrain under the rover.

A lot has been made of the difficulty of getting to Mars, and historically there have been far more failures than successes (24 versus 15), but the Americans' recent record at the Red Planet is actually very good - six successful landings versus two failures.

Even so, Nasa continues to downplay expectations.

"If we're not successful, we're going to learn," said Doug McCuistion, the head of the US space agency's Mars programme.

"We've learned in the past, we've recovered from it. We'll pick ourselves up, we'll dust ourselves off, we'll do something again; this will not be the end.

"The human spirit gets driven by these kinds of challenges, and these are challenges that drive us to explore our surroundings and understand what's out there."

Curiosity is heading for Gale Crater

The mission team warned reporters on Saturday not to jump to conclusions if there was no immediate confirmation of landing through Odyssey.

There were "credible reasons", engineers said, why the UHF signal to Odyssey could be lost during the descent, such as a failure on the satellite or a failure of the transmitter on the rover.

Continued efforts would be made to contact Curiosity in subsequent hours as satellites passed overhead and when Gale Crater came into view of radio antennas on Earth.

"There are situations that might come up where we will not get communications all the way through [to the surface], and it doesn't necessarily mean that something bad has happened; it just means we'll have to wait and hear from the vehicle later," explained Richard Cook, the deputy project manager.

This was emphasised by Allen Chen, the EDL operations lead. His is the voice from mission control that will be broadcast to the world during the descent. He will call out specific milestones on the way down. He told BBC News there would be no rush to judgement if the Odyssey link was interrupted or contained information that was "off nominal".

"I think we proceed under any situation as though the spacecraft is there, and there for us to recover - to find out what happened," he said.

"That's the most sensible thing to do. There are only a few instances I think where you could know pretty quickly that we'd be in trouble."

Step by step: How the Curiosity rover will land on Mars

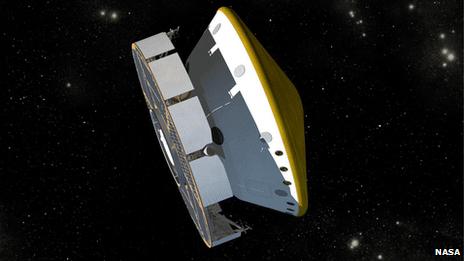

As the rover, tucked inside its protective capsule, heads to Mars, it dumps the disc-shaped cruise stage that has shepherded it from Earth.

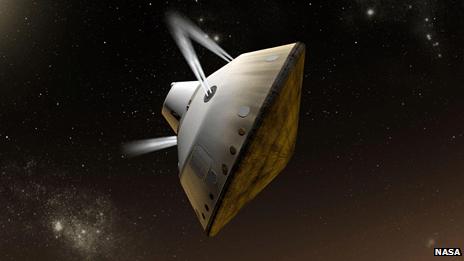

The capsule hits the top of the atmosphere at 20,000km/h. It ejects ballast blocks and fires thrusters to control the trajectory of the descent.

Most of the entry vehicle's energy is dissipated in the plunge through the atmosphere. The front shield heats up to more than 2,000C

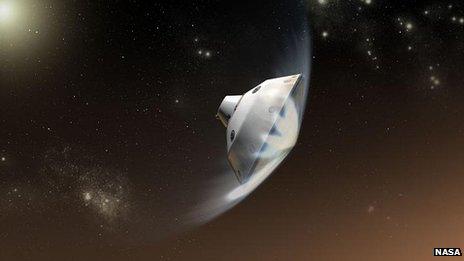

The parachute deploys when the capsule is about 11km above the ground but still moving at supersonic speed

A key event is the dropping of the heat shield - this permits imaging and radar instruments to monitor the approaching surface

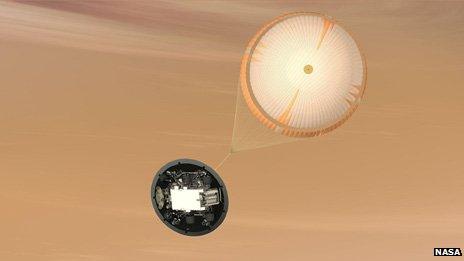

At about 1.5km above the ground and still moving at 80m/s, the rover and its sky crane drop away from the parachute and capsule backshell

Rockets on the sky crane slow the descent to 1m/s; cords spool the rover to the surface; the cords are then cut and the crane flies away to a safe distance

The rover is equipped with a nuclear battery and should have ample power to keep rolling across the Martian surface for many years

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published4 August 2012

- Published30 July 2012

- Published3 August 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published25 May 2012

- Published26 November 2011

- Published24 November 2011

- Published22 July 2011