Nasa's Curiosity rover lifts its navigation cameras

- Published

The distant hills are part of the rim of Gale Crater. Note also the two dark circular patches in the foreground. These are scour marks left by Curiosity’s rocket-powered descent crane

The Curiosity Mars rover has lifted its mast and used its high navigation cameras for the first time.

The robot vehicle has returned black and white images that capture part of its own body, its shadow on the ground and views off to the horizon.

Spectacular relief - the rim cliffs of the crater in which the rover landed - can be seen in the distance.

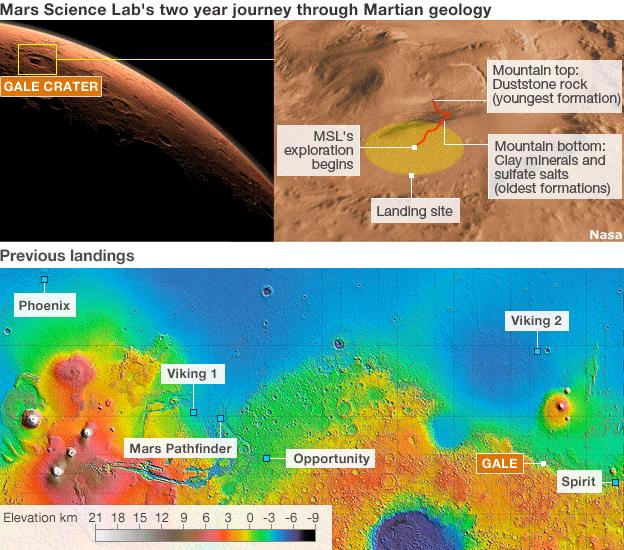

Curiosity - also known as the Mars Science Laboratory, MSL - put down on the Red Planet on Monday (GMT).

The US space agency (Nasa) mission came to rest on the floor of a deep depression on Mars' equator known as Gale Crater, close to a 5.5km-high mountain.

The plan eventually is to take the robot to the base of this mountain where it is expected to find rocks that were laid down billions of years ago in the presence of liquid water.

Justin Maki: Curiosity has a number of navigation cameras

Curiosity will probe these sediments for evidence that past environments on Mars could once have favoured microbial life.

Since its landing, engineers have been running through a list of health checks and equipment tests.

These have included deploying a high-gain antenna to provide a data link to Earth additional to the UHF satellite relays it uses most of the time. This antenna failed to point correctly at first, but the problem has now been fixed.

The mast was stowed for the journey to Mars, lying flat on the deck of the rover.

Raising it into the vertical was the main task of Sol 2 - the second full Martian day of surface operations.

Curiosity's mast casts a shadow on the ground

Locked in the upright position, the masthead and its cameras stand some 2m above the ground.

Curiosity has two pairs of black and white, greyscale, navigation cameras which can acquire stereo imagery to help the rover pick a path across the surface.

These Navcams sit just to the side of two science cameras - one wideangle, one telephoto. It is these Mastcams that will provide the really exquisite, true colour views of the Martian landscape. We should see something of their output following Sol 3.

But the Navcam images are already providing a great deal of information.

"You can see in the near-field the scour marks the descent engines made on the surface," noted Justin Maki, a curiosity imaging scientist.

"Go all the way out to the horizon and you can see the north rim of Gale Crater. This image is fantastic, especially for all of us who've developed these cameras, and based on what we've done in the last 12 hours we've declared the Navcams commissioned and ready for use."

The thruster marks in the ground have certainly piqued the interest of Curiosity project scientist, John Grotzinger.

Don Hassler: Rad also gathered data on the cruise to Mars

"What's cool about this is that we got some free trenching," he said.

"We see our first glimpse of bedrock. Apparently there is a harder rockier material beneath this veneer of gravel and pebbles. So we're already getting a look into the subsurface."

He also remarked how Earth-like the vista appeared, joking: "You would really be forgiven for thinking that Nasa was trying to pull a fast one, and we actually put a rover out in the Mojave Desert and took a picture - a little Los Angeles smog coming in there." (He was referring to the haze over the distant cliffs)

Most of the pictures we have seen so far have been low-resolution thumbnails - easy to downlink. But we are now starting to get one or two hi-res versions also.

Mardi captures the moment the heatshield falls away under the descending rover still on its parachute

Mike Malin, the principal investigator on Mardi (Mars Descent Imager), has released a detailed view taken of the 4.5m-wide heatshield as it fell away from the rover's capsule during Monday's entry, descent and landing (EDL).

"You've been hearing us say, 'just wait until you see the good stuff'. Well, this is the good stuff coming down, and it's quite spectacular," said Dr Malin.

"You can actually see the stitching in the thermal blanket; there's wiring in there also for the [heatshield sensors]."

Eventually hundreds of Mardi pictures will be run together to make a movie of the descent.

With the rover now on the ground and Mardi still pointing downwards, Dr Malin has also got a good shot of the gravel surface under the vehicle.

Gravel surface: Mardi remains in a downward-looking mode and is held about 70cm from the surface

One instrument on the rover has already had a chance to gather some data. This is the Radiation Assessment Detector (Rad).

Indeed, this instrument has acquired quite a lot of data so far, as it was working for periods even during the rover's cruise to Mars.

It is endeavouring to characterise the flux of high-energy atomic and subatomic particles reaching Mars from the Sun and distant exploded stars.

The Navcams are making a rover self-portrait. A hi-res version will follow this thumbnail version

This radiation would be hazardous to any microbes alive on the planet today, but would also constitute a threat to the health of any future astronauts on the Red Planet.

"We turned up on the 100th anniversary of Victor Hess's first measurements of galactic cosmic rays on Earth, which was quite appropriate," said Rad principal investigator Don Hassler.

"We took about 3.5 hours of observations. Sometime next week we'll start taking routine measurements," he told BBC News.

In other news, Nasa reports it has now found more components of the landing system discarded by the rover during EDL.

These are a set of six tungsten blocks that the rover's capsule ejected to shift its centre of mass and help guide its flight through the atmosphere.

Satellite imagery has identified the line of craters these blocks made when they slammed into the ground about 12km from Curiosity's eventual landing position.

Nasa has also confirmed the precise timing of Monday's touchdown.

The rover's computer put this at 05:17:57 UTC on Mars. With a one-way light-travel time of 13 minutes and 48 seconds to cover the 250 million km to Earth, this equates to a receive time here at mission control at the agency's Jet Propulsion Laboratory of 05:31:45 UTC (GMT).

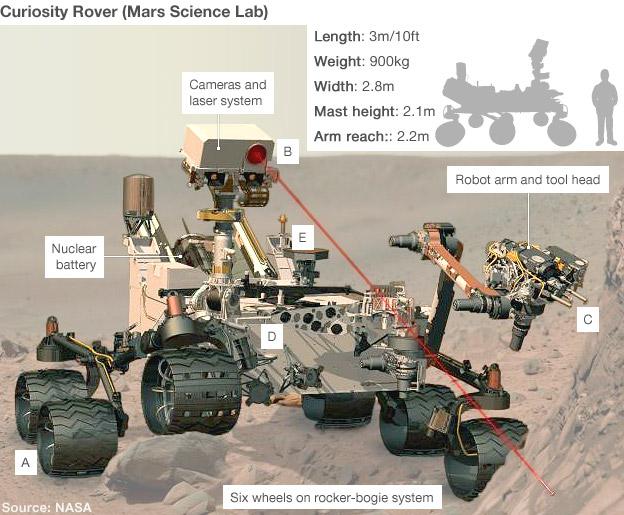

(A) Curiosity will trundle around its landing site looking for interesting rock features to study. Its top speed is about 4cm/s

(B) This mission has 17 cameras. They will identify particular targets, and a laser will zap those rocks to probe their chemistry

(C) If the signal is significant, Curiosity will swing over instruments on its arm for close-up investigation. These include a microscope

(D) Samples drilled from rock, or scooped from the soil, can be delivered to two hi-tech analysis labs inside the rover body

(E) The results are sent to Earth through antennas on the rover deck. Return commands tell the rover where it should drive next

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published7 August 2012

- Published7 August 2012

- Published6 August 2012

- Published6 August 2012

- Published4 August 2012

- Published5 August 2012

- Published25 May 2012

- Published30 July 2012

- Published4 August 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published26 November 2011

- Published24 November 2011

- Published22 July 2011