Herschel space telescope to go blind

- Published

- comments

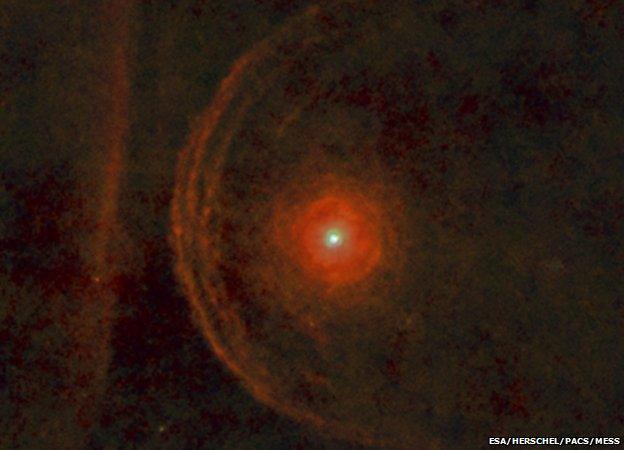

Herschel has built a huge catalogue of far-infrared and sub-mm images of the sky. This recently released image shows the layers of gas shed by Betelgeuse, one of the most familiar stars in the night sky

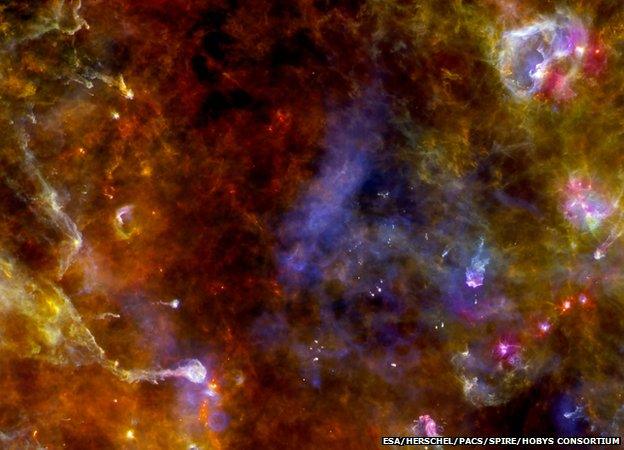

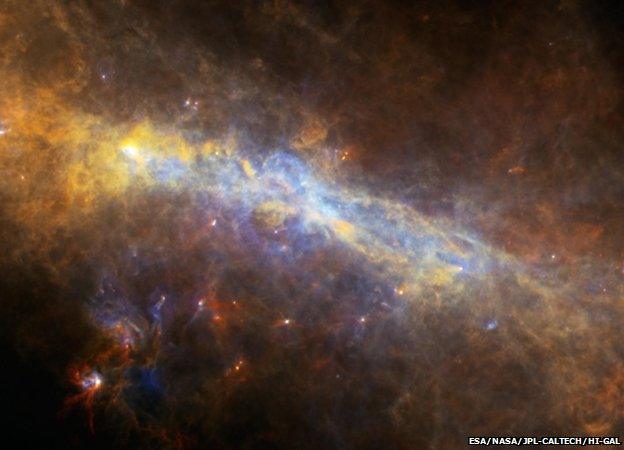

Herschel will be remembered as the telescope that produced great vistas of gas and dust, as here in the constellation of Cygnus. Invisible to optical telescopes like Hubble, these billowing clouds and threading filaments trace the locations where future stars will form

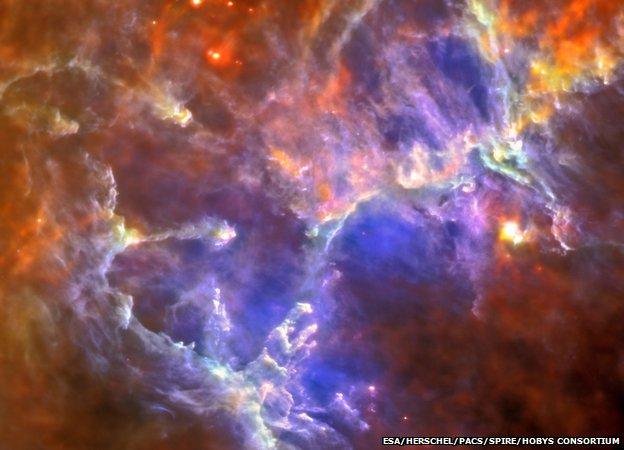

With its far-infrared detectors, Herschel has been able to re-visit familiar objects to provide new data. This picture shows the classic “Pillars of Creation” in the Eagle Nebula, in the constellation Serpens. At long wavelengths, the clouds of gas and dust in the pillars glow, revealing processes at play in star formation

Herschel has sought to study the evolution of galaxies. In this image taken of a small patch of sky in the constellation of Ursa Major, countless galaxies are recorded. Some of these fuzzy blobs are many billions of light-years distant

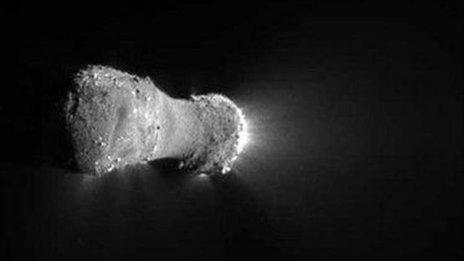

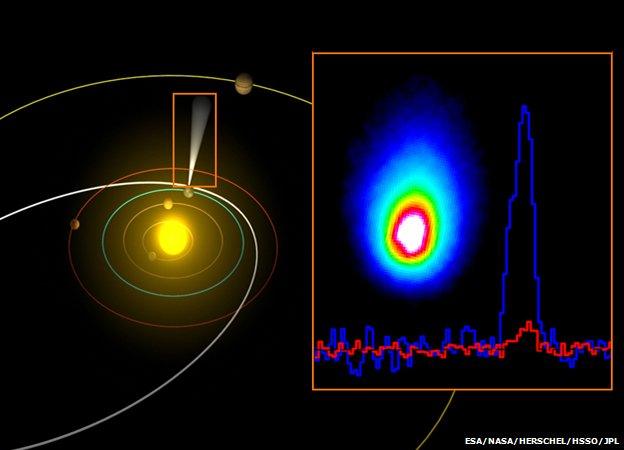

One of Herschel's instruments is called HIFI. The spectrograph's job is to untangle the chemistry of space. Its study of Comet Hartley 2 showed the object to have water-ice with a similar composition to Earth's oceans

At a relatively close distance of 2.5 million light-years, Andromeda is very similar in size to our own Milky Way Galaxy. Here, Herschel's observations (orange) are combined with the Newton XMM telescope's (blue)

Herschel's view of RCW 120, a bubble of gas and dust in space around a massive star. Another huge star, 8-10 times the mass of our Sun, is forming on the bubble's boundary - seen as a bright white object

Herschel has revealed new things about our own galaxy. Here, looking towards the centre of the Milky Way, it spies a ribbon of cold gas and dust that is more than 600 light-years across and which appears to be twisted. Scientists have yet to explain it

The European Space Agency (Esa) is about to lose the use of one of its flagship satellites.

Since 2009, the billion-euro Herschel telescope has been unravelling the complexities of star birth and galaxy evolution.

But its instruments employ special detectors that need to be chilled to fantastically low temperatures.

The helium refrigerant that does this job will run out in a few weeks and when it does, Herschel will go blind.

The coming demise of the telescope is no surprise. It is occurring just as was forecast at the start of the mission, almost to the month.

Researchers are now busy running through a final list of observations, acquiring as many images as they can in the time left available.

Already, thousands of pictures have been deposited in the Herschel archive, which is set to become a key reference source for decades into the future.

"I think there is a consensus in the community that Herschel has been a tremendous success and that we have made beautiful observations," Esa project scientist Dr Göran Pilbratt told BBC News.

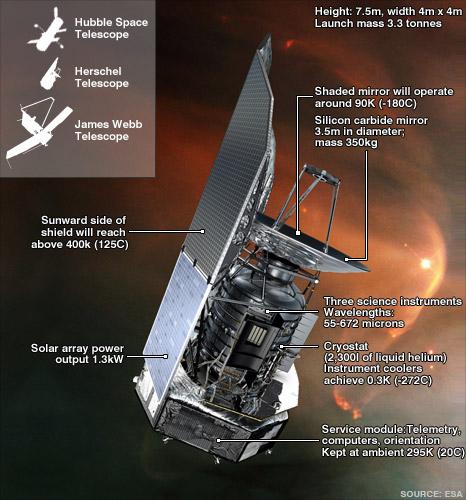

The telescope was launched almost four years ago and sent to an observing position 1.5 million km from Earth.

It was equipped with a 3.5m mirror - the largest monolithic mirror ever flown - and three state-of-the-art instruments sensitive to long wavelengths of light, in the far-infrared and sub-millimetre range (55 to 672 microns).

The Herschel telescope has to be kept extremely cold to study its frigid targets

This technology has allowed Herschel to study the processes at play as large clouds of gas and dust collapse to form new stars. Its deep vision has also enabled scientists to trace the story of how galaxies have changed through cosmic time.

But the design of the instruments, and in particular of their detectors, has required Herschel be operated close to absolute zero (-273.15C).

This has been achieved with the aid of a cooling system run on superfluid helium, more than 2,000 litres of which were loaded into the telescope at launch.

The cryogen has gradually boiled off during the course of the mission, and the latest calculation from engineers is that it will be gone entirely sometime in the final two weeks of this month.

Once the detectors start to warm from their ultra-frigid state, they will stop working. The end, when it happens, will be quite sudden.

Those astronomers in the queue to use Herschel at that moment will no doubt be disappointed, but also philosophical: observing time was allocated on the basis that the opportunity could not be guaranteed as the mission moved into its end phase.

Some engineering tests will be conducted on the telescope in April. The Esa operations team will then put the satellite into a slow drift around the Sun before ceasing all communications.

Prof Matt Griffin, from Cardiff University, is team leader on the Spire instrument, which is sensitive to some of the longest wavelengths. He said the telescope had exceeded all expectations.

"It will be a sad day when it makes its last observation, but the data that it has collected during its lifetime will keep astronomers busy for years," he told BBC News.

"For the next three years, the Spire team will work hard to put all Spire data into the best possible condition to be as easy as possible to access and to use in the future.

"Amongst Herschel's most exciting results have been the detection of many thousands of distant star-forming galaxies that are helping us understand how galaxies formed and evolved over cosmic time, and the mapping out in our own galaxy of the filaments and cores that are the sites of new suns being formed today."

- Published25 September 2012

- Published18 February 2012

- Published17 January 2012

- Published13 January 2012

- Published6 October 2011