The first fractions of a second after the Big Bang

- Published

- comments

"I'm hoping there's something surprising there for them. If they just say, 'well, other people were right' - that's not exciting; the last decimal places are never very interesting. What we want is some new phenomenon."

American Nobel Laureate John Mather, external believes the bar has been set very high for the European Space Agency's (Esa) Planck surveyor, external.

The satellite was launched in 2009 to make temperature maps of the sky, and on Thursday this data will finally be released to the worldwide scientific community.

There is great hope that Planck will be able to tell us what happened in the first fractions of a second after the Big Bang when the Universe that we can observe today occupied almost no space at all. And by fractions, we mean about a millionth of a billionth, of a billionth, of a billionth of a second after it all got going.

To get at this information, Planck has sampled the "oldest light" in the cosmos - the light that was finally allowed to spread out across space once the Universe had cooled sufficiently to permit the formation of hydrogen atoms.

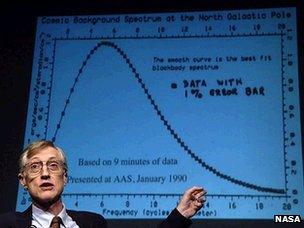

John Mather's work on the CMB with COBE earned him a Nobel Prize in 2006

Before that time, about 375,000 years into the life of the cosmos, conditions would have been so hot that all the light would have been bounced around and trapped in a fog of ionised matter. The Universe would have been opaque.

The "fossil" light is still evident today. It bathes the Earth in a near-uniform glow which, thanks to the expansion of the Universe, can now be found at microwave frequencies.

Its temperature profile has also dropped to just 2.7 degrees above absolute zero, with only a minute excess of warmth or cold either side of this signal depending on where you look on the sky.

These temperature fluctuations reflect differences in the density of matter when the light parted company and set out on its journey.

American satellites, including Mather's historic COBE mission in 1989, external, have already extracted astonishing insights from this Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation. These include refined estimates for:

The age of Universe - 13.7 billion years old

Its contents - 4.6% atomic matter; 24% dark matter; and 71.4% dark energy

Its shape - it is "flat", meaning space adheres to Euclidean geometry, where straight lines can be extended to infinity and the angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees, etc.

The ignition of the first stars - now timed to have occurred some 400 million years after the Big Bang

"Planck has the extra sensitivity and resolution to retrieve yet more information," the Nasa scientist told BBC News. "The question then is: have they done the right things with the data?"

The European team behind Planck will present maps of the sky in nine frequencies - six more than COBE, and three more than its US successor, WMAP, which flew in 2001, external.

This broader sweep was designed to give the Esa mission a sharper, cleaner view of the CMB, and the minuscule fluctuations in temperature that are seen around that mean of 2.7 kelvins (-270C).

It is with this keener vision that Planck will endeavour to find "some new phenomenon", not at 375,000 years after the Big Bang but long before then.

Information encoded in the satellite's maps should also tell us about "inflation, external", the faster than light expansion that cosmologists believe the Universe may have experienced in its first fleeting moments.

Inflation has become the accepted add-on to Big Bang theory in the past 30 years, even though its physics is highly speculative. Scientists like the concept because it would explain some important observations, not least the geometry of space - a superluminal expansion could have stretched everything until it was flat. The tiny quantum fluctuations that drove the expansion could also have given rise to small variations in the amount of matter from one place to another, seeding the later gravitational growth of stars and galaxies.

But there are numerous models for how inflation might have worked. They cannot all be right.

"What we need to do now is back some of these models into the corner, and Planck can help us do that," said Prof Andrew Jaffe from Imperial College London.

One of the ways scientists study the CMB is by subjecting the warm and cold spots in the radiation to a detailed statistical analysis, examining the deviations in temperature as a function of their size on the sky - their angular scale.

This produces a characteristic wiggle on a graph, a so-called power spectrum, which can then be matched against theoretical expectation.

Inflation - if it happened - predicts that this spectrum should be ever so slightly tilted; and WMAP has seen evidence for this.

"It's not yet very precisely determined but this is one of the instances in which Planck will make a real difference," explained Prof Bruce Partridge of Haverford College, Philadelphia.

"Because it has high resolution, it is spanning a wide range of angular scale. And what you want to do to see a slight tilt with respect to angular scale is to have as large a lever arm as possible, and Planck will do that," he told BBC News.

Another prediction of inflation is that the CMB should be gaussian. If you pick up all the temperature data points in the sky map and put them in histogram, you should get a nice bell curve.

Bruce Partridge discusses the significance of the CMB

"If it's not gaussian then we have to re-think inflation or maybe inflation is more complicated than the simplest models suggest," said Prof Marc Kamionkowski from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Planck's capabilities mean it will provide one of the best checks yet for non-gaussianity.

The ultimate test, however, would be to look for a special signal in the CMB referred to as B-Modes.

Most models of inflation suggest the expansion would have been accompanied by ripples of gravitational energy. These should have been imprinted on the fossil light in its polarisation.

Even if they are there, these B-modes will be very hard to detect, and the Planck team does not intend to make a statement on the issue until a further year of analysis has been completed.

Nonetheless, Thursday's announcement is likely to make some important statements on inflationary tests. A whole swathe of models will probably be confined to the bin at the end of the day.

Esa's Planck project scientist, Dr Jan Tauber, will not be drawn on the findings before the release in Paris. Asked to describe the new temperature maps, he says merely: "They're beautiful."

- Published27 August 2012

- Published13 January 2012

- Published3 August 2011

- Published11 January 2011

- Published27 November 2010