Space debris collisions expected to rise

- Published

Fortunately, there have been very few collisions in orbit so far

Unless space debris is actively tackled, some satellite orbits will become extremely hazardous over the next 200 years, a new study suggests.

The research found that catastrophic collisions would likely occur every five to nine years at the altitudes used principally to observe the Earth.

And the scientists who did the work say their results are optimistic - the real outcome would probably be far worse.

To date, there have been just a handful of major collisions in the space age.

The study was conducted for the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee., external

This is the global forum through which world governments discuss the issue of "space junk" - abandoned rocket stages, defunct satellites and their exploded fragments.

The space agencies of Europe, the US, Italy, the UK, Japan and India all contributed to the latest research, each one using their own experts and methodology to model the future space environment.

Simulated futures

They were most concerned with low-Earth orbit (that is, below 2,000km in altitude). This is where the majority of missions returning critical Earth-observation data tend to operate.

All six modelling groups came out with broadly the same finding - a steady increase in the numbers of objects 10cm and bigger over the 200-year period.

This growth was driven mostly by collisions between objects at altitudes between 700km and 1,000km.

The low-end projection was for a 19% increase; the high-end forecast was for a 36% rise. Taken together, the growth was 30%. These are averages of hundreds of simulations.

For the cumulative number of catastrophic collisions over the period, the range went from just over 20 to just under 40.

Somewhat worryingly, the forecasting work made some optimistic assumptions.

One was a 90% compliance with the "25-year rule". This is a best-practice time-limit adopted by the world's space agencies for the removal of their equipment from orbit once it has completed its mission.

The other was the idea that there would be no more explosions from half-empty fuel and pressure tanks, and from old batteries - a significant cause of debris fragments to date.

Concept development

"We're certainly not at 90% compliance with the 25-year rule yet, and we see explosion events on average about three times a year," explained Dr Hugh Lewis, who detailed the research findings at the 6th European Conference on Space Debris, external in Darmstadt, Germany, on Monday.

"It is fair to say this is an optimistic look forward, and the situation will be worse than what we presented in the study," the UK Space Agency delegate to the IADC told BBC News.

"So one message from our study is that we need to do better with these debris-mitigation measures, but even with that we need to consider other approaches as well. One of the options obviously is active debris removal."

Research groups around the world are devising strategies to catch old rocket bodies and satellites, to pull them out of orbit.

Previous modelling work has indicated that removing just a few key items each year could have a significant limiting effect on the growth of debris.

Most ideas include attaching a propulsion module to a redundant body, perhaps via a hook or robotic clamp.

Harpoon idea

One UK concept under development is a harpoon. This would be fired at the hapless target from close range.

The harpoon has barbs on the end that would grip the space debris object

A propulsion pack tethered to the projectile would then tug the junk downwards, to burn up in the atmosphere.

When the BBC first reported this concept back in October, the harpoon was being test-fired over a short range of just 2m.

The latest testing, to be reported at the Darmstadt conference this week, has seen the harpoon fired over a much longer distance and at a more realistic, rotating target.

"Our tests have progressed really well, and everything seems to be scaling as expected," explained Dr Jaime Reed, from Astrium UK.

"We've now upgraded to a much more powerful gun and have been firing the harpoon over 10m - the sort of distance we'd expect to have to cover on a real debris-removal mission.

"Our harpoon also now has a shock absorber on it to make sure it doesn't go too far inside the satellite, and we've been firing it with the tether attached. It's very stable in flight."

Chinese test

There are some 20,000 man-made objects in orbit that are currently being monitored regularly. About two-thirds of this population is in Low-Earth orbit.

These are just the big, easy-to-see items, however. Moving around unseen are an estimated 500,000 particles ranging in size between 1-10cm across, and perhaps tens of millions of other particles smaller than 1cm.

All of this material is travelling at several kilometres per second - sufficient velocity for even the smallest fragment to become a damaging projectile if it strikes an operational space mission.

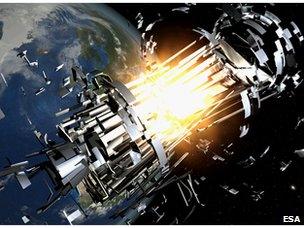

Two key events have added significantly to the debris problem in recent years.

The first was the destructive anti-satellite test conducted by the Chinese in 2007 on one of their own retired weather spacecraft.

The other, in 2009, was the collision between the Cosmos 2251 and Iridium 33 satellites.

Taken together, these two events essentially negated all the mitigation gains that had been made over the previous 20 years to reduce junk production from spent rocket explosions.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published2 October 2012

- Published26 March 2012

- Published26 October 2011

- Published2 September 2011

- Published2 September 2011