Is comet landing mission worth the cost?

- Published

Can the argument over funding be won with pretty pictures?

Prof Monica Grady's reaction to the first landing on the surface of a comet shows just what the Rosetta mission means to scientists.

Jumping up and down on the spot before hugging the BBC's science editor David Shukman, her joy was emblematic of that felt by virtually all of the people who have worked for years to make this mission happen.

"There are generations of people - managers who have replaced other managers - who were there to see this event. They've invested their entire lives in this mission," Rosetta's flamboyant project scientist Matt Taylor told the BBC after the landing.

It's far too early to assess whether the mission has been a success - or otherwise.

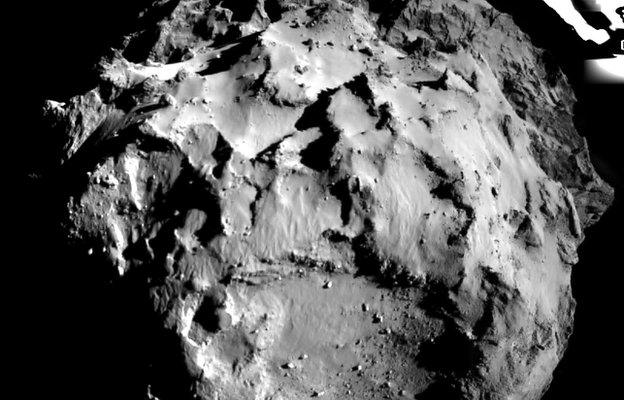

The probe took a decade to catch up with its target comet, travelling six billion km.

Landing on one of these icy cosmic time capsules, with their meagre gravity and precarious terrain, was always going to be dicey.

But it didn't help that two out of three mechanisms designed to help affix Philae to the surface failed.

Professor Monica Grady jumps for joy: "It's landed - I've waited years for this"

The probe appears to have bounced about one kilometre above the surface after first touching down.

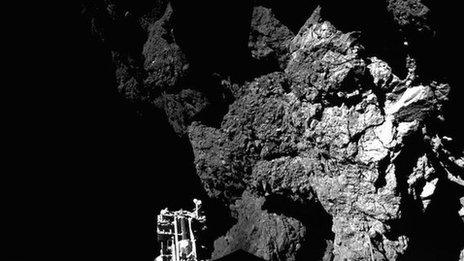

As I write, there are suggestions it may be lying at an angle, some way from the original landing zone so much time and effort was spent choosing.

It may be on a slope, in the shadow of a cliff - which makes it difficult to get enough sunlight to charge its batteries.

Whatever the outcome, and the science returned, there will always be questions about the costs of such missions and whether they can be justified in the current financial climate.

On Twitter, Dr Taylor responded to just such a question by borrowing a catchphrase from A-Team actor Mr T: "I pity the fool.", external

Thomas Reiter, director of human spaceflight and operations at Esa, acknowledged how the top line figure of 1.4bn euros appeared.

But he explained: "If you divide it by the 20 years that the development and the mission has cost, it's about cents per European citizen per year that was contributing to this new knowledge."

Four planes

According to physicist Andrew Steele, who has calculated the costs, external on his website Scienceogram, the Rosetta mission cost 3.50 euros per person from 1996-2015. This works out at 0.20 euros per person per year.

The same amount of money could buy four A380 planes. In the period since the mission was agreed, the Rosetta mission has created hundreds of jobs.

The funding source for space missions like Rosetta comes from a subscription, paid by each of the 20 member states of the European Space Agency (Esa).

In 2013, the UK paid a contribution of £240m to Esa's total budget of £3.3bn (4.2bn euros).

Dr Sarah Main from the Campaign for Science and Engineering (Case) points to the potential benefits that basic scientific enquiry - of the sort that Rosetta represents - can yield.

"Forms of enquiry about the world around us, which we're summarising here as basic research, are vital to making changes to our society and our quality of life," she told BBC News.

"Whether they come as a downstream effect of the building blocks of basic research work someone else has done, or in a more deliberately applied way. You can make parallels with cancer research: you can't design a new cancer drug unless you understand the mechanisms that cause cancer in a cell."

Dr Main cites the example of the World Wide Web, which grew out of a system designed to help particle physicists at Cern communicate more effectively.

"There are also a number of studies which assess the economic value of research in general. That's taking any type of research - as esoteric as you like - and adding it up to say: What does that deliver to the economy?

"We see significant returns on investment from government putting funds into scientific research. It directly causes the economy to grow. One study showed it caused the economy to grow by 20% three years later."

Mission facts:

Philae lander

Travelled 6.4 billion km (four billion miles) to reach the comet

Journey took 10 years

Planning for the journey began 25 years ago

Comet 67P

More than four billion years old

Mass of 10 billion tonnes

Hurtling through space at 18km/s (40,000mph)

Shaped like a rubber duck

Comet 67P explained in 60 seconds

Indeed, as Oxford University astronomer Chris Lintott put it, external when quizzed on BBC Newsnight earlier this year: "The money doesn't go to the comet, the money's spent here on Earth. It goes to people, it goes on technology and it goes to industries in this country and throughout Europe."

There is also the hope that such high profile events can inspire the young scientists and engineers of the future.

A recent increase in numbers of A-level students taking physics at university was linked by some to better teaching, but others acknowledge a groundswell of popular interest in these subjects which may be fuelled by a greater profile in the media.

But the Rosetta mission shouldn't be viewed as a recruiting tool alone. Thomas Reiter says the science designed to be carried out by the mission cuts to the very heart of the quest to understand where we come from.

"It's to find answers to very fundamental questions about the history of our own planet, how it evolved... If life really emerged on Earth or if it might have been brought to Earth by such comets many billion of years in the past.

"I think this is really worth it."

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.

- Published13 November 2014