Rosetta will prompt science images rethink

- Published

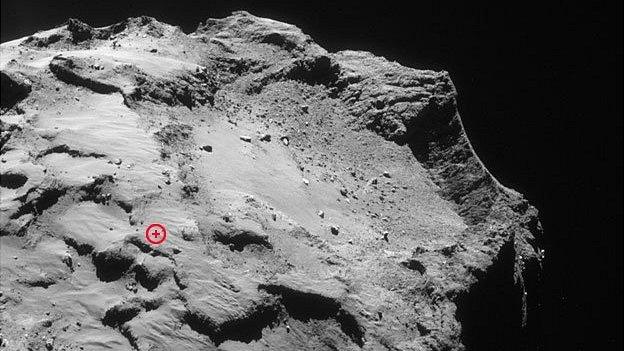

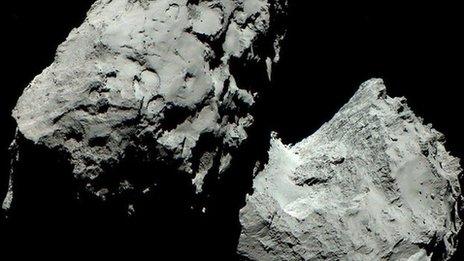

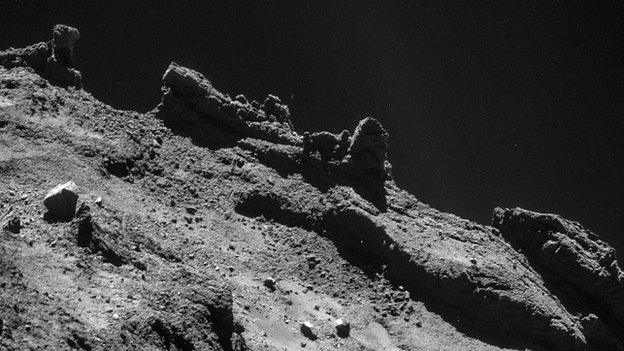

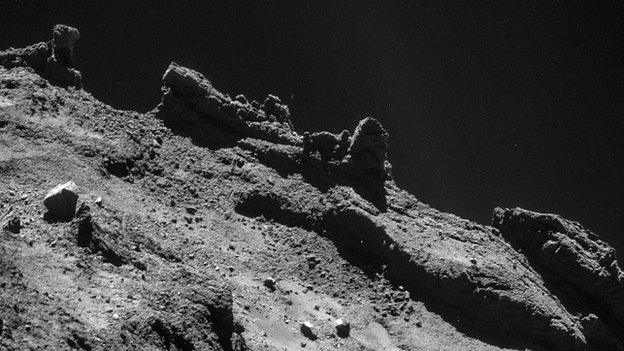

Enthralling subject: Mr Dordain's comments were made just as a new science camera image of the comet was released

The European Space Agency needs to find a new way for images and other data acquired by its science missions to come out into the public domain.

That is the view of the organisation's director general, Jean-Jacques Dordain.

He was expressing his frustration at not seeing more pictures from the main camera system on Esa's Rosetta probe, which is tracking Comet 67P.

These images are subject to a six-month embargo to allow the mission team to make discoveries without being scooped.

But the policy has upset the thousands of ordinary members of the public who follow Rosetta on a daily basis because they are not being shown the very best views that have been acquired.

Nearly all of the images seen to date have come from the probe's navigation cameras. The products of its science cameras, on the other hand, which are far superior, have been given only a very limited release because of the proprietary period.

"Even I've tried to get more data," Mr Dordain said. "I might be the DG but I'm also a fan of Rosetta and [its lander] Philae. It's a problem; I don't deny it's a problem. But it's a very difficult problem, too," he told BBC News.

"I understand the frustration of the public and the media, but, on the other hand, I understand the position of the principal investigators who have invented the mission."

Mr Dordain was speaking in Paris at his annual New Year breakfast with reporters.

Even handed

Esa itself has little control over the release of imagery from its science missions. This is partly due to the way these ventures are organised and funded.

The agency procures the satellite platform, the launch rocket and runs day-to-day operations, but the instruments that gather the data are supplied - and funded - via national member states.

Esa may drive the truck, but it does not own the merchandise in the back.

Giving scientists on particular instruments a proprietary period has become standard practice.

It provides the researchers with a head start, enabling them to be first to announce major discoveries and to publish the details in the top journals.

The credit and citations that follow boost their ability to propose future programmes and win further funding. This process has become central to the way they work.

"If these science missions exist, it's largely because of the principal investigators who come up with these wonderful ideas and supply these instruments. And their whole life is about coming up with the discovery first. So, one can hardly blame them for that," Mr Dordain said.

"Maybe what we should do is distinguish better between data that would be considered absolutely key to making scientific discoveries and can be kept under wraps before publication [in journals], and the data that can be released to the public much sooner."

Supercharged discovery

The DG said that current arrangements needed to be adhered to (on all sides), but added that polices as a whole should be reviewed.

The issue has become high profile now for a number of reasons.

First, Comet 67P has enthralled the public, and they naturally want to see more of it.

Secondly, the emergence of very accessible image processing software, combined with the rise of social media, has put new tools into the hands of enthusiasts who wish to play with pictures and to share them.

But a third problem is that the old practices have started to rub up against newer models for doing science.

An example of this would be the data policies that underpin the Sentinel Earth-observation satellites that Esa is building and managing for the European Commission. The first of these spacecraft, a radar platform called Sentinel-1a, became operational late last year.

All of its pictures are being given away free, with no priority access.

The view is that this will supercharge discovery and even create new businesses in Europe that can exploit the data.

Operational since October, Sentinel-1a has been pumping out images without restriction

So far, in the few months that Sentinel-1a has been working, 4,700 users have registered for access to its data, and 150,000 images have already been distributed.

The next big Esa planetary missions that will have to address the issue (and it is predominantly the planetary missions that this matter affects) will be the ExoMars ventures. The agency has a satellite going to the Red Planet in 2016, and a rover that will land in 2019. Both will send back pictures.

The principal investigator for the rover's science cameras is Prof Andrew Coates, from the UK's Mullard Space Science Laboratory at University College London.

He said his team was discussing the image policy right now, and added that as far as he was concerned he wanted it to be "as open as possible".

But he cautioned that there were limits, and that the intellectual investment still had to be credited somehow.

"There's a lot of work that goes into this, a lot of calibration to make sure [the camera system] is giving you the right illumination, the right colours. There's lots of work behind the scenes," he told me when we discussed science data policies on this month's Space Boffins podcast, external.

The camera team on the ExoMars rover is working through its policy now, four years ahead of launch

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published5 January 2015

- Published17 December 2014

- Published2 April 2014

- Published12 December 2014

- Published10 December 2014

- Published18 November 2014

- Published17 December 2014

- Published17 June 2015