African synchrotron bid gathers pace

- Published

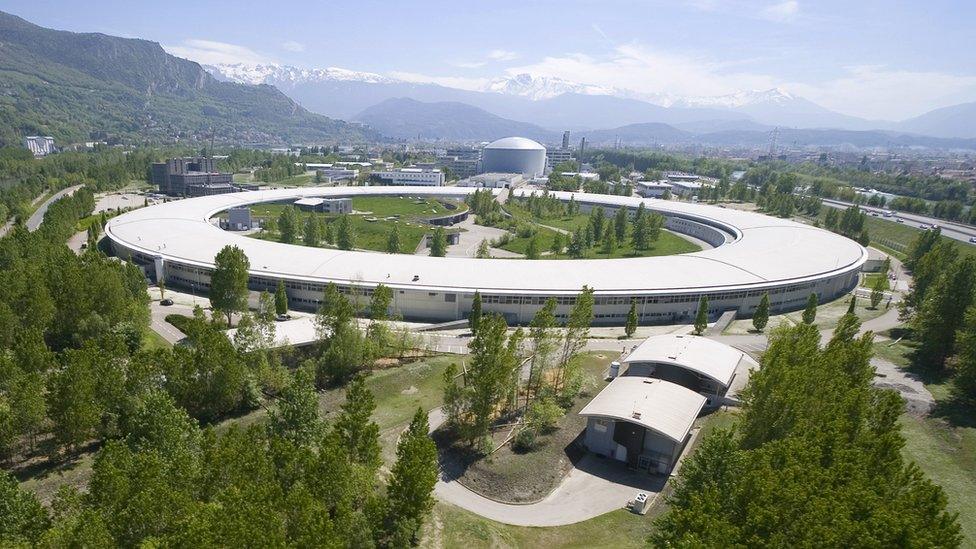

The European synchrotron ESRF in Grenoble will host the meeting in November

The effort to build a synchrotron in Africa is gaining momentum, a leading proponent has told a US conference.

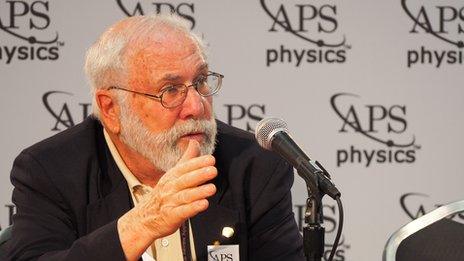

Prof Herman Winick said a key meeting of scientists and officials has been scheduled for November.

A synchrotron is a big accelerator that produces powerful X-rays for research; apart from Antarctica, Africa remains the only continent without one.

The effort will be modelled on a Middle East synchrotron which resulted from a landmark international collaboration.

Prof Winick, an eminent physicist from Stanford University and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California, highlighted the uneven scattering of the 50-plus light sources on a world map.

"Glaring on this map is the absence of any red dot here," he said, pointing to the African continent.

"It's very relevant that Africa has such facility, so that dedicated, motivated African scientists can work on problems - biomedical, environmental - that are of particular interest to that region."

So far the initiative has a 15-strong steering committee that includes members from several African countries as well as the US and Europe.

It is these scientists who have called the November workshop, to be hosted by the ESRF (the European synchrotron in Grenoble, France).

"It will bring together scientists and government officials from all over Africa," Prof Winick said.

Team effort

'I'd have to check my life expectancy': Prof Winick hopes to see an African light source in 10-15 years

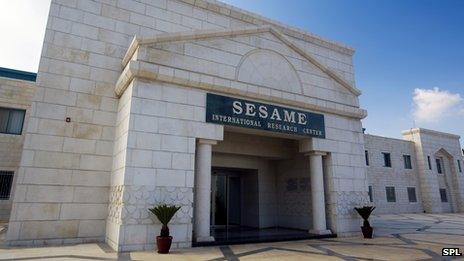

The Middle East project is known as Sesame (Synchrotron-light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East). It is situated in Jordan and brings together nine countries across that region - spanning national boundaries where diplomatic relations can be tense.

It is due to start making light in 2015 and like Cern, it was built with funds from its member countries along with support from Unesco.

Prof Winick hopes a similar model will be fruitful for the proposed "African Light Source".

"It's like Cern- you need to get these countries together, and the important thing is that they take collective responsibility for the project," he told the BBC.

"You're talking $200m, depending on construction costs."

Jordan's Sesame facility was the result of a groundbreaking international effort

Asked for a timeframe, the professor, who also spearheaded the initial stages of Sesame, said: "I'd have to check my life expectancy before answering that question.

"It's really 'T zero' for this project - it's just getting started. I think it will be at least 10 years; I hope it's not 15.

"Sesame only started in 1997, and it's scheduled to come online with its first X-rays in 2015."

Also speaking at the American Physical Society's March Meeting was Antonio Jose Roque da Silva, director of Brazil's LNLS light source. It was the first synchrotron in the southern hemisphere.

The LNLS is about to be outstripped by a brand new, state-of-the-art Brazilian facility, Sirius, which began construction in December.

Prof da Silva said this was evidence that building such a giant contraption seeds further scientific development.

"As the users got better, they demanded more," he said. "The impact for science in Brazil has been huge."

The two physicists also stressed the importance of such facilities for reversing the "brain drain" to better equipped countries. PhD students, for example, can be trained locally in the various fields that use the X-ray beams - from biomedicine to agriculture and even archaeology.

"X-rays are a stupendous tool for studying all kinds of materials, and every part of the world needs them," Prof Winick said.

Sekazi Mtingwa, a nuclear physicist at MIT and another member of the steering committee, agrees. He told BBC News: "Such a light source would be the single most important scientific instrument for revolutionizing science, technology and innovation in Africa."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external.

- Published26 November 2012

- Published27 March 2013

- Published4 July 2014