What is the point of the Large Hadron Collider?

- Published

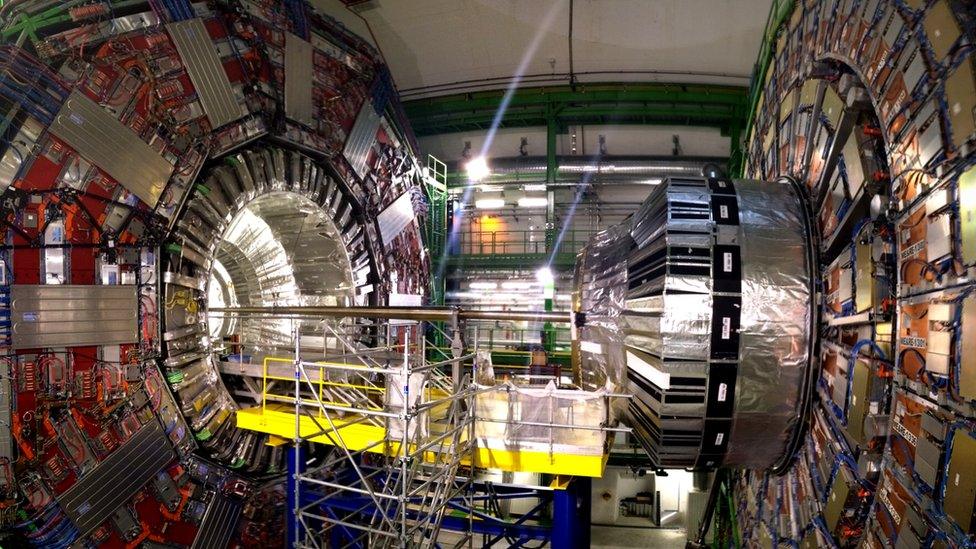

No small undertaking: the experiments occupy huge subterranean caverns

Every time fundamental research hits the headlines you can be sure that someone - maybe lots of people - will question whether it's worth it.

And so it is with the restart of this mother of all physics experiments, ready after its two-year upgrade to explore uncharted corners of the sub-atomic realm.

This vast machine ranks as one of the world's biggest experiments, with incredibly sophisticated machinery filling a 27km circular tunnel, and the bill so far has come to a little under £4 billion.

Back in 2008, when the vast device was first brought to life, one senior British scientist grumbled to me that "the particle physicists seem to get all the money they want".

Sound and fury?

His view was that humanity faces a long list of severe and immediate threats which are more deserving of the kind of massive scientific investment devoted to the research at Cern.

Top of his list was clean energy. If we could start with a blank sheet of paper, he said, would we really choose to devote all those billions to particle physics?

I heard a similar complaint on the day that the Rosetta spacecraft achieved its historic rendezvous with a comet far beyond Mars.

As the mission controllers erupted around me, one of my tweets attracted a sternly-worded demand to know how anyone would benefit from this venture to a distant and icy rock.

"What good," I was asked, "might any knowledge that it might obtain do for mankind?"

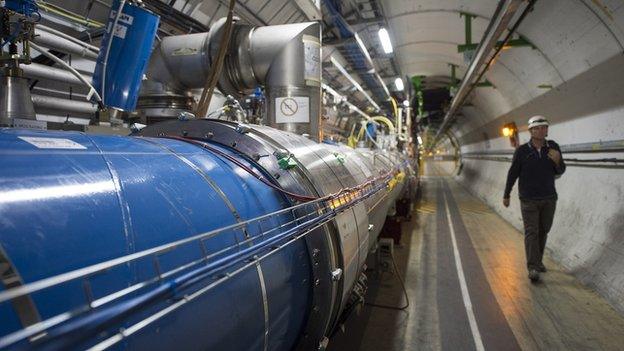

Why do we need a 27km tunnel for smashing particles together at almost the speed of light?

One answer might be pragmatic: if a comet ever headed our way, it would be good to know what they are made of and how they might be deflected.

Another could be that it would surely satisfy our curiosity to know if comets were the source of our water or even of life itself.

But a response that feels more compelling is that previous generations have only been able to gaze at comets in awe or fear while ours might be the first to understand them.

Eye opener

The same kind of argument applies to the Large Hadron Collider.

When it discovered the famous Higgs boson, and confirmed its position in the Standard Model of physics, that was an extraordinary achievement in its own right.

It proved the existence of an invisible process that performs the fundamentally important role of giving all other particles their mass or substance.

Big stuff, but did it change anything practical in our everyday lives? Of course not.

But it is a huge step on a journey towards understanding how the universe works, and there is much more to come.

The massive engineering challenge posed by the collider has already produced spin-offs

The next collisions of protons may reveal something about the majority of matter that exists but has yet to be seen - the stuff known as dark matter.

They may uncover evidence for the weird notion that there are extra dimensions, or hordes of previously unseen particles that form pairs with the ones we know about.

Any of this would open our eyes to a new way of perceiving the fabric of everything we see and touch - how it is made and what holds it together.

Astounding though these discoveries may be, they would not by themselves alter anything tangible about how we get up the next day, to face our lives and our work.

Long view

But that is how science functions. A new insight can open a door and it's then up to other researchers to choose whether to venture through it, sometimes decades later, to develop practical applications.

For example, the fact that we live in an age of electronics did not come down to a single discovery overnight.

Its roots can be traced to the brilliant theorisers and experimenters who did fundamental work back in the 19th century - Michael Faraday, James Clerk Maxwell and J.J. Thomson to name but a few.

The cost of the LHC so far comes to just under £4bn

So who knows if the Higgs boson or dark matter particles or extra dimensions may eventually lead to some similarly huge leap in the next 50-100 years?

The Cern case is that we will never know unless the basic job of exploration is done now.

Back in the 1960s, when Nasa was under pressure to justify the cost of the Apollo moon landings, it resorted to highlighting spin-offs.

The lunar missions, it argued, had given technology a unique boost and produced such wonders as miniaturised electronics and the non-stick frying-pan.

And that kind of spin-off is another key part of Cern's case.

It can claim credit for inventing a system for sharing data around the globe: the World Wide Web.

Born of fundamental research which at the time might have felt irrelevant, it enables you to read this article now.

- Published24 March 2015

- Published16 March 2015

- Published5 March 2015

- Published15 February 2015

- Published10 July 2014

- Published1 July 2014