Rosetta comet lander tells magnetic story

- Published

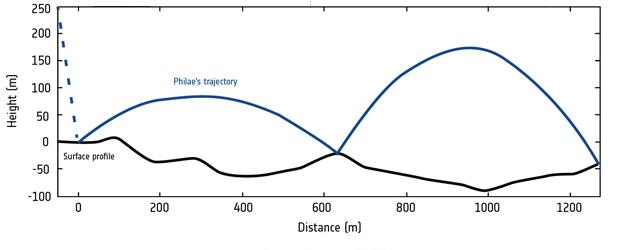

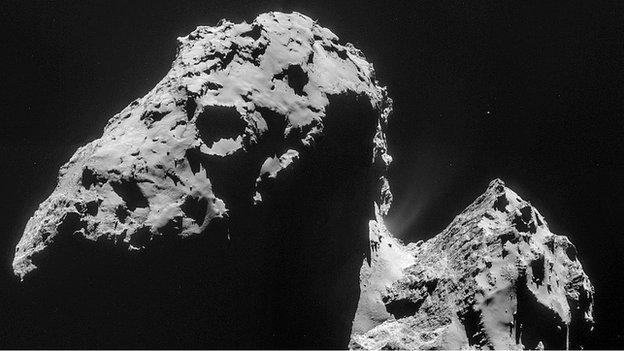

Philae landed on the smaller lobe of the comet, touching the surface four times before coming to a rest

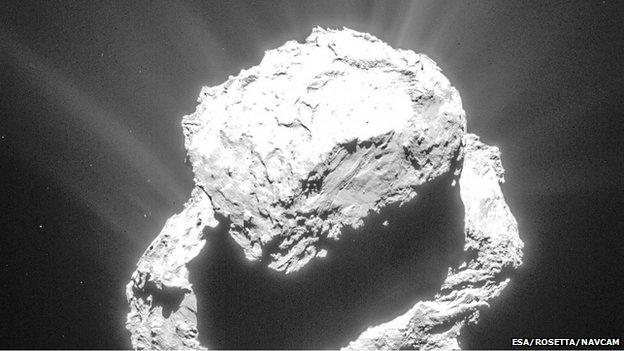

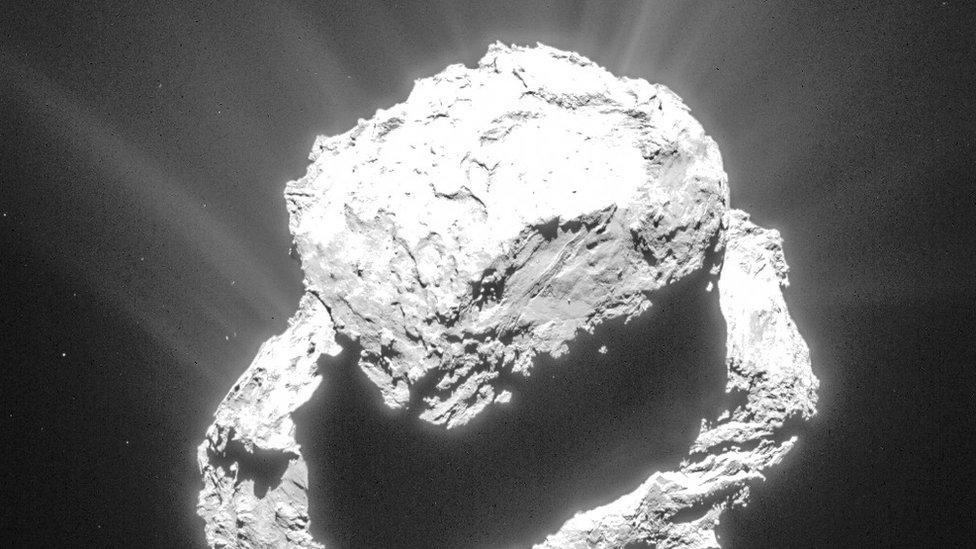

The comet being trailed through space by Europe's Rosetta probe has no magnetic field of its own.

The finding is significant because it answers one of the major questions of the mission - namely, did magnetic fields play a major role in pulling together the material that makes up icy dirt-balls like 67P?

On this evidence, it would seem not.

Other formation processes must have been paramount in the nascent Solar System, 4.5 billion years ago.

Researchers working on the European Space Agency mission released their assessment here at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly meeting. They have also published a paper in the journal Science, external.

The data to support the discovery comes in part from the spacecraft Rosetta, but also from its lander Philae, which was dropped on to the surface of 4km-wide 67P last November. Both carry sensitive magnetometers.

When the "mothership" and lander parted company, they began a series of measurements of their local environment.

The pair could sense not only the magnetic field carried in the solar wind streaming off the Sun, but their interactions with it as they moved.

In the case of Philae, this allowed scientists to understand changes in direction and even the action of onboard electronic equipment and the deployment of structures such as legs and booms.

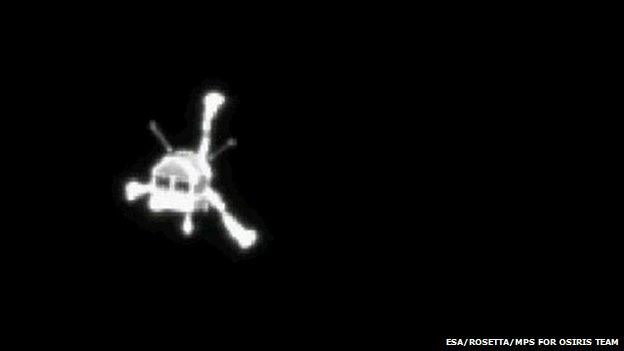

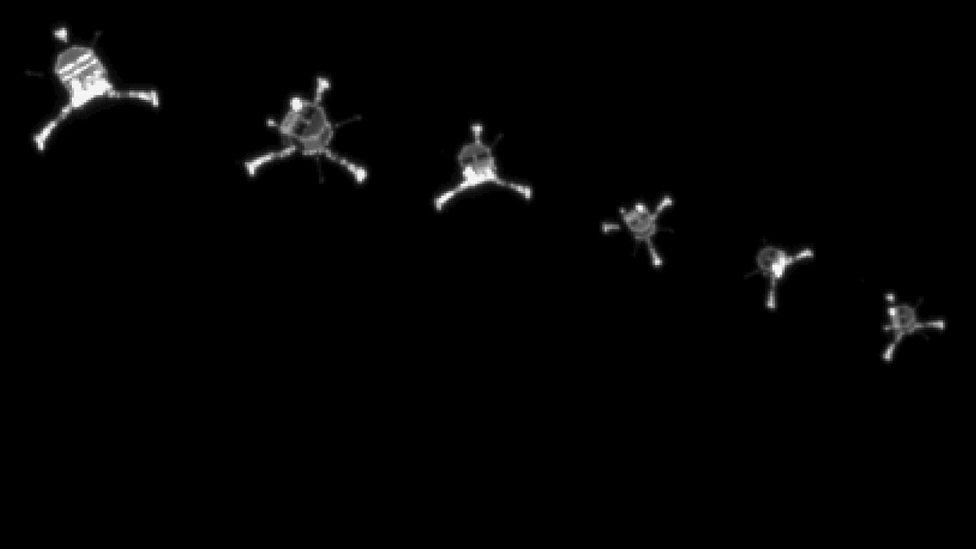

Philae deployed legs and a magnetometer boom as it descended to the surface

In the data, researchers can see the moment Philae first touches the surface of Comet 67P. It is detected in the movement of the magnetometer boom and a change in rotation.

Famously, the robot bounced, and data indicates that after a period of 46 minutes, and after covering a distance of some 630m, Philae made its next contact with the surface. But this is clearly a glancing blow with a cliff structure, because the interpretation of the data is that the robot starts tumbling.

A further 600 metres into its unexpected journey across the comet, Philae made a more solid touchdown, before briefly lifting up again and coming to rest, finally, in the dark ditch it managed to photograph just prior to running out of battery power. From first to fourth contact is a separation of 117 minutes.

Philae bounced more than 1,200m across the surface before stopping in a ditch

To tell this full story, scientists had to pull together a range of other information gathered during the descent, but the critical observation is that throughout the bouncing, Philae saw no correlation between the strength of the magnetic field and its height above the surface. This is not consistent with 67P itself being responsible for that field. The only field being sensed was the one carried in the solar wind.

A less magnetic history

If there was an intrinsic field, Philae would have seen its strength increase as it got closer to the surface, and decrease as it moved away (after the glancing blow, it moved 240m above the surface).

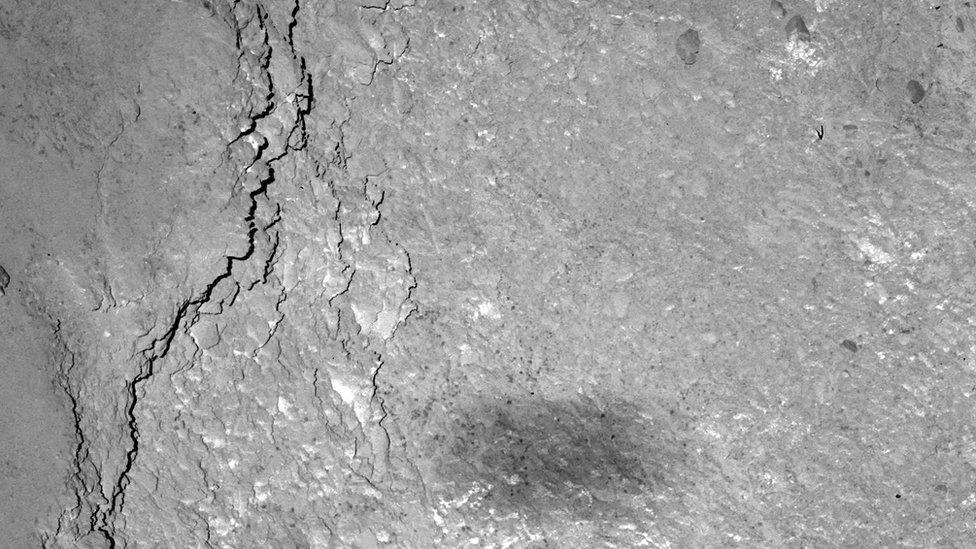

This is not to say materials at the surface are not magnetised. Some clearly are; dust particles will include iron in the form of magnetite.

But the interpretation is that the comet in general would betray a global signal had magnetic fields played a prominent role during formation by aligning and clumping together the particles from which it is made.

"We know of course that our spatial resolution is limited by the distance between the sensor and the surface, so we can only say something about magnetisation for scales of one metre or larger," explained Hans-Ulrich Auster, who leads the Romap instrument on Philae.

"We can say nothing about millimetre of centimetre-scale particles, but for these larger particles we can exclude that magnetic forces have played a role in the accumulation of planetary building blocks."

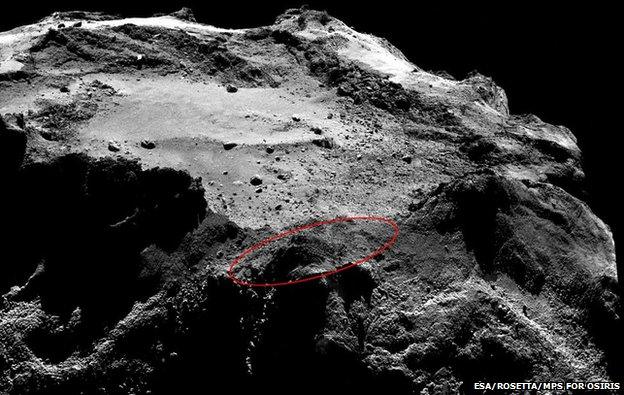

The mission team has a good idea of where the Philae robot ought to be

And Karl-Heinz Glassmeier, who works on Rosetta's magnetometer, added: "We feel that the magnetic fields in the early Solar System must have been much smaller than previously thought - because if they had been larger, we most probably would have seen a much larger magnetisation at the comet."

To give an idea of the sensitivity of the measurements - the instruments are detecting signals down to 2 nanoTesla. By contrast, a magnetometer at the surface of the Earth would register a reading in the order of 50,000nT.

Fears for Philae

Scientists do not know precisely where Philae is resting on Comet 67P. They have a good idea, to within 30-50m - but one of the interesting asides from this research is that they do know now very well, to within a few degrees, the orientation of the lander.

The onboard magnetometer acts like a compass, and the last reported data tells the team which way Philae's legs and feet must be pointing.

Meanwhile the search for the lander goes on. Rosetta is now routinely listening out for a call from the robot.

The last image Rosetta took of Philae as the robot bounced over the rim of a cliff

If enough light can get into its dark ditch to illuminate its solar panels, Philae should be able to boot up. This could happen as the comet moves closer to the Sun in the next 3-4 months.

The German space agency's lander manager, Stephan Ulamec, is cautious, however. He has concerns about the temperature in the ditch. If it is very cold, generated electricity would be diverted to heating the robot, not transmitting a signal to Rosetta.

"We have been very, very cold now in the period of hibernation, which could cause damage to electronics boards," he told BBC News.

"Also, in order to wake up, we need a temperature of at least minus 45C, and this could explain why we've had no contact with Philae yet."

Sending Rosetta closer to the comet to try to photograph the robot's location once again seems to be out of the question. 67P is throwing off so much gas and dust that the probe gets confused about its position in space relative to the stars, which it uses for navigation.

"We are at a distance of about 100km and stepping closer, but how closer we can get I just can't say at the moment. It could well be that now we have to stay at a considerable stand-off location," said Matt Taylor, the Esa Rosetta project scientist.

August is when the comet will be closest to the Sun and at its most active. Only towards the end of the year will the emissions begin to die back.

Stephan Ulamec: "Honestly, I'm concerned about the temperature. We've been very, very cold."

- Published20 March 2015

- Published17 March 2015

- Published3 March 2015

- Published30 January 2015

- Published22 January 2015