Seeking comet splatter on Mercury

- Published

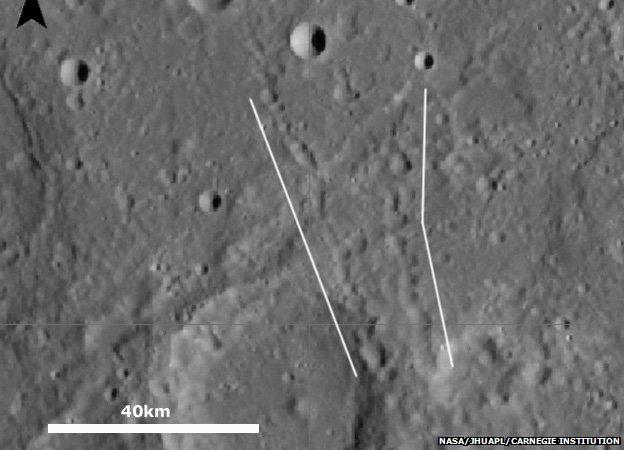

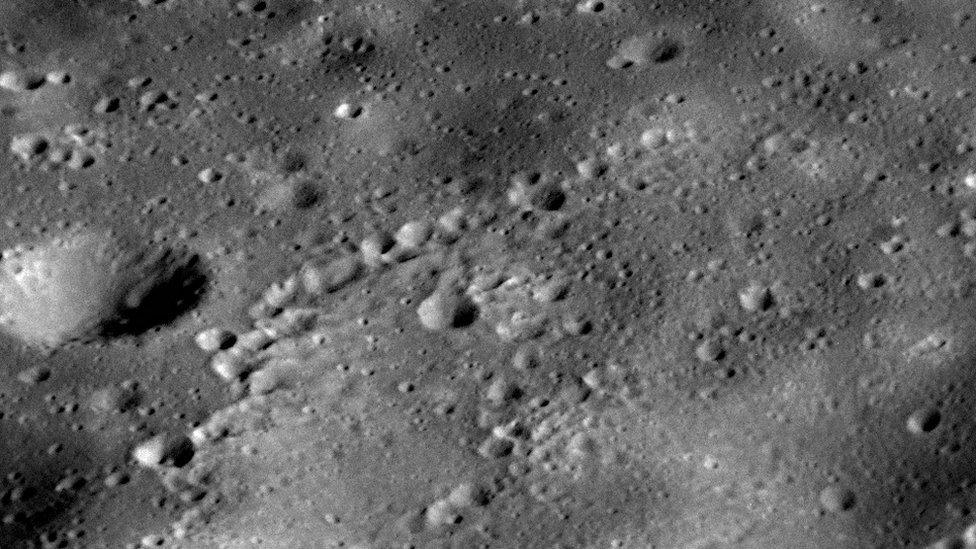

Are these strings of depressions the result of sequential impacts by tidally disrupted comets?

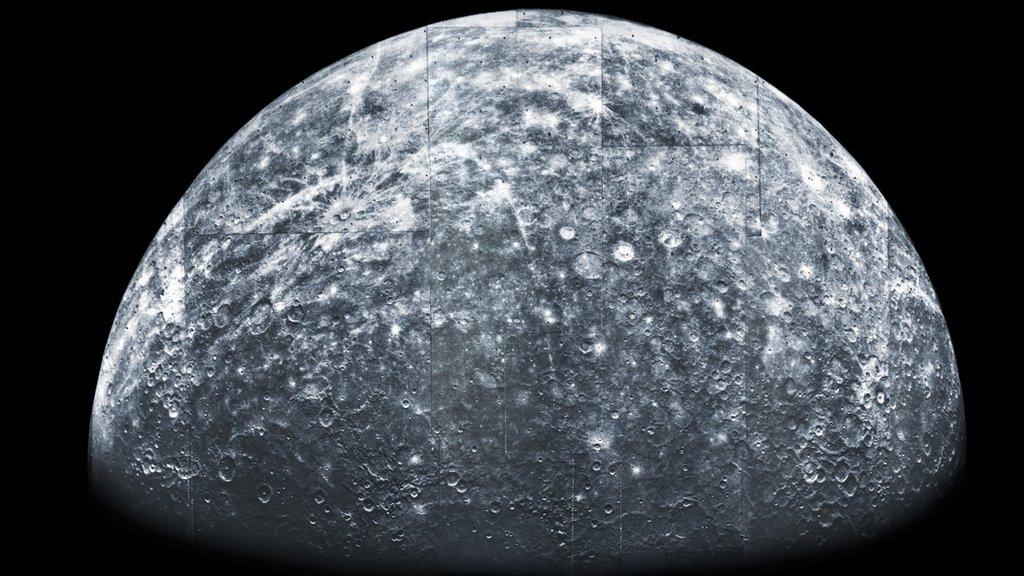

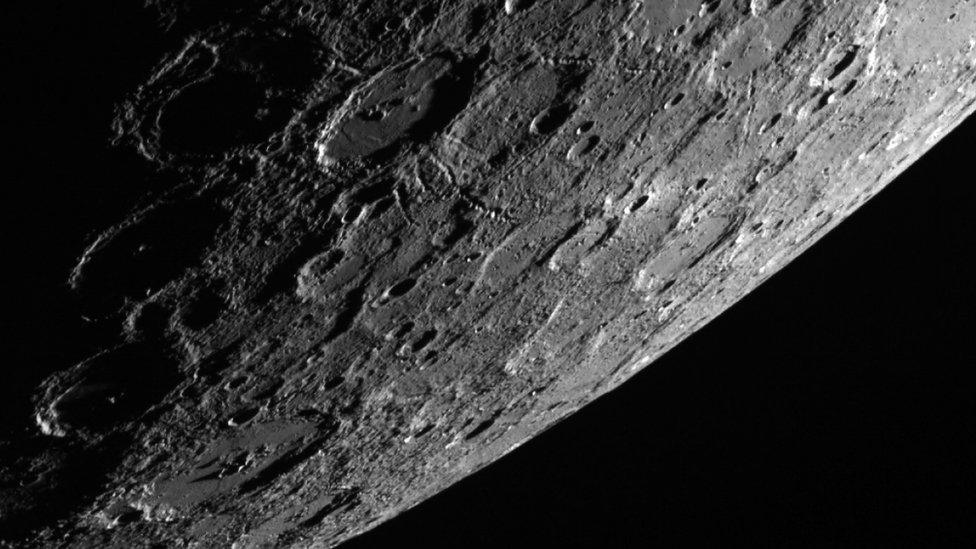

UK scientists are hunting for impact craters on Mercury that are likely to have been produced by disrupted comets.

They are looking for chains of depressions known as catenae.

These would have formed when comets passed too close to the Sun and broke apart under tidal forces into many pieces, and then splattered the surface of the Solar System's innermost world.

The Open University team is examining pictures returned from the US space agency's (Nasa) Messenger probe.

This satellite, which is expected to end operations on Thursday with a crash of its own on to Mercury, has already revealed some extraordinary insights into the planet's past relationship with comets.

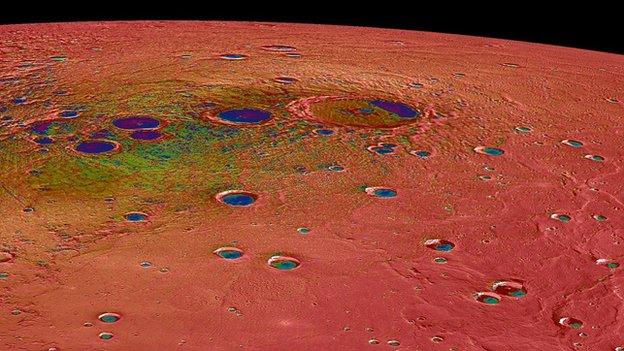

Many of the ices and other volatile compounds seen in permanently shadowed craters at the poles were most probably delivered by the frozen wanderers.

Likewise, the blackened hue of some surface deposits may indicate a dusting of carbon-rich material derived from comets that have hit Mercury.

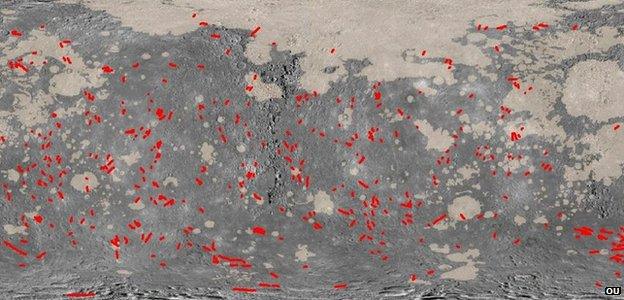

Rothery and Fegan have identified hundreds of catenae on the surface of Mercury

Given its position so close to the Sun, one would expect the planet to have been pelted by the countless icy dirt-balls that routinely get drawn in to graze our star.

And tidally fragmented comets would have done so as a train of objects, having been dislocated in the Sun's immense gravity field.

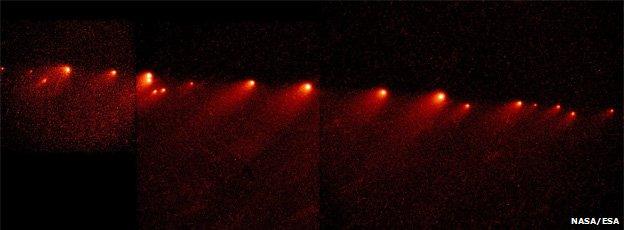

Something very similar is seen out at Jupiter where comets that have got too close to the gas giant will crumble and then sequentially splatter its moons.

Hubble famously caught sight of Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 broken apart by Jupiter's gravity

An example of a likely comet-produced catena on Jupiter's moon Ganymede

David Rothery and Emma Fegan have been poring over Messenger images, trying to determine how many of the 500 or so crater chains they have identified on Mercury are evidence of this same process of tidal disruption.

Many of the catenae are unarguably the result of debris that was flung out of primary impact bowls (dug out by intact colliding comets or asteroids). These ejecta strings form radial patterns that can be traced back to an obvious source.

The chains Rothery and Fegan are attempting to distinguish, on the other hand, have no clear origin. They appear isolated.

And, intriguingly, when they plot the orientation of these suspect catenae, they appear to betray a bias. More seem to point north-south than east-west. If confirmed, this may say something about the early population of comets in the Solar System.

"It could be that we're seeing the north-south ones more easily because of the direction of sunlight, but these are pretty big features - kind of hard to miss," explained Prof Rothery.

"If there are genuinely more catenae orientated north-south than east-west, it's suggesting that if they're produced by tidally disrupted comets then the comets that were hitting Mercury more than three billion years ago had orbits tilted at more or less ninety degrees to the plane of Mercury's orbit."

The idea is somewhat speculative at the moment, but fascinating nonetheless.

Prof David Rothery: "Many of the chains of craters can be traced back to a big basin"

Although the image stream from Messenger is about to end, the next probe to Mercury is already under construction.

BepiColombo, external is a joint venture between the European and Japanese space agencies.

Its mission will launch in 2017 and arrive in orbit in 2024. Prof Rothery is the lead co-investigator on Bepi's Mercury Imaging X-ray Spectrometer (MIXS), which has been designed by a team at Leicester University.

He presented his and Fegan's catenae research at the recent European Geosciences Union General Assembly in Vienna, Austria, external.

The European-Japanese BepiColombo mission is currently in development

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published30 April 2015

- Published17 March 2015

- Published30 March 2015

- Published30 November 2012