Messenger closes in on Mercury crash-landing

- Published

The probe, illustrated soaring above Mercury, has been in orbit around the planet since March 2011

After more than a decade in space and four years orbiting Mercury, Nasa's Messenger mission is set to reach its explosive conclusion.

The spacecraft is expected to crash into the planet's surface at 20:26 BST on Thursday; it made its final powered manoeuvre on 28 April.

After reaching Mercury in 2011, Messenger has far exceeded its primary mission plan of one year in orbit.

It is only slowly losing altitude but will hit at 8,750mph (14,000km/h).

That means the 513kg craft, which is only 3m across, will blast a 16m crater into an area near the planet's north pole, according to scientists' calculations.

All of Messenger's fuel, half its weight at launch, is completely spent; its last four manoeuvres, extending the flight as far as possible, have been accomplished by venting the helium gas normally used to pressurise actual rocket fuel into the thrusters.

The high-speed collision, 12 times faster than sound, will obliterate this history-making craft. And it will only happen because Mercury has no thick atmosphere to burn up incoming objects - the same reason its surface is so pock-marked by impact craters.

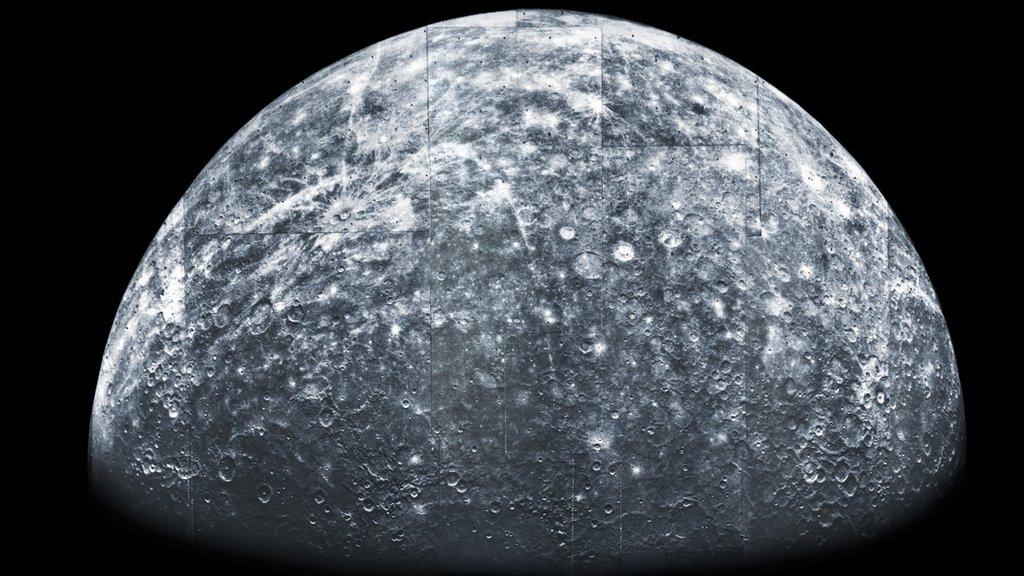

Mission scientists have released this illustration showing Messenger's calculated impact location

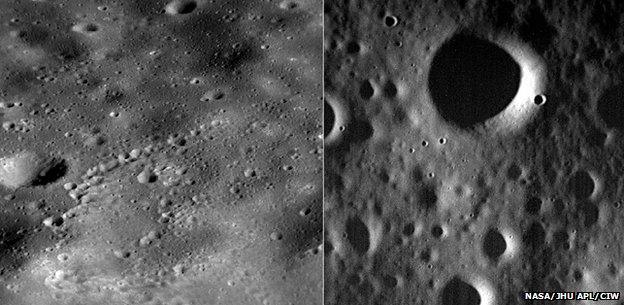

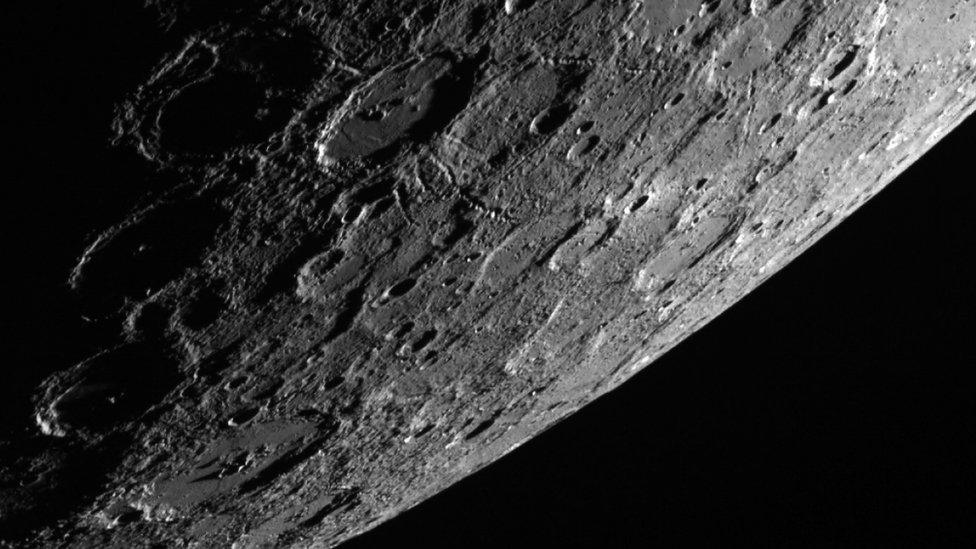

These are some of Messenger's final images, snapped on 26 and 29 April

During its twice-extended mission, Messenger (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) transformed our understanding of Mercury. It sent back more than 270,000 images and 10 terabytes of scientific measurements.

It found evidence for water ice hiding in the planet's shadowy polar craters, and discovered that Mercury's magnetic field is bizarrely off-centre, shifted along the planet's axis by 10% of its diameter.

Skimming the surface

Messenger traces a highly elliptical orbit around Mercury, drifting out to a distance of nearly twice the planet's diameter before swinging to within 60 miles (96km) at closest approach. To maintain this pattern in the face of interference from the Sun, it needed a blast of engine power every few months - but its fuel tanks are now empty.

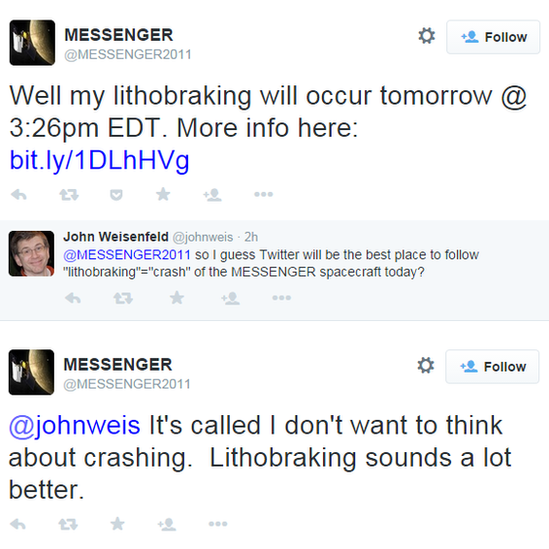

The Messenger Twitter account has been active in the run-up to the crash

After circling the planet 4,104 times, Messenger made its penultimate pass at a distance of between 300 and 600 metres - one or two times the height of the Eiffel Tower - at about 13:00 BST on Thursday.

"If you could see that, it would be a real spectacle," said Jim Raines, the instrument scientist on the craft's FIPS instrument (Fast Imaging Plasma Spectrometer) and a physicist at the University of Michigan. "It would cross the horizon in just a second or two, flying low overhead at ten times the speed of a supersonic fighter."

The next time it swings back close to Mercury's surface, eight hours later, it will be curtains for Messenger; the impact has been precisely modelled using maps produced by the craft's own data.

Mercury has towering cliffs left by its shrinking, wrinkling history, but the predicted path has Messenger missing these.

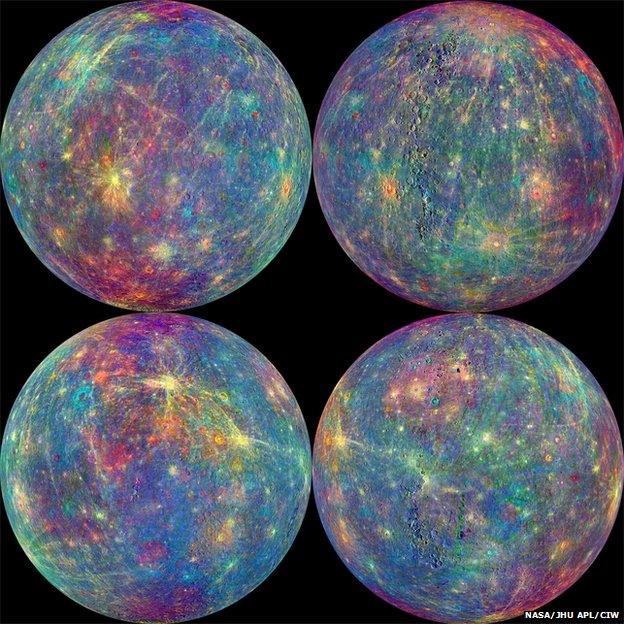

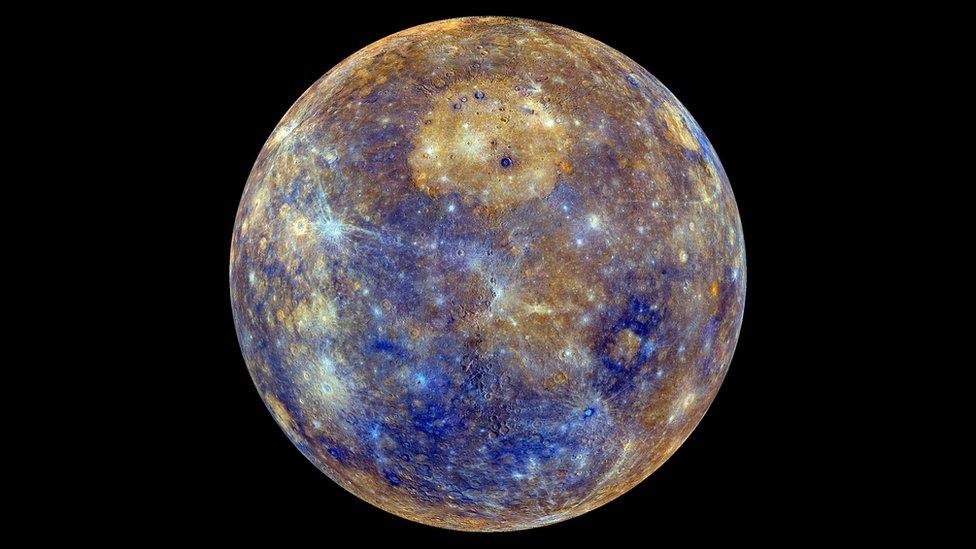

Messenger compiled this coloured map of Mercury during its first year in orbit

"It's a pretty flat area of the planet," said Nancy Chabot, the instrument scientist on the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), Messenger's twin cameras. "It's going to be a skimming impact."

But it will leave a mark.

"It will probably be an oblique crater... because the impact angle will be so shallow, so grazing to the surface. But at over 8,000 miles per hour, it's going to make a crater."

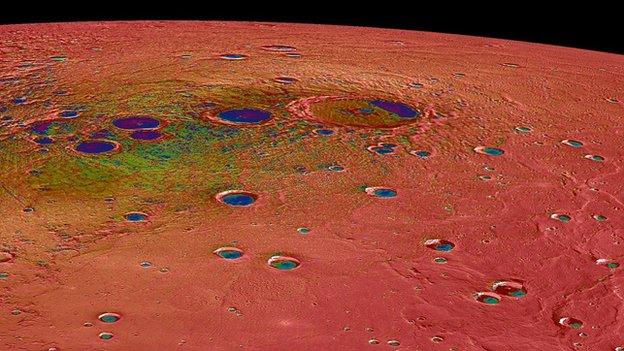

These new images overlay chemistry measurements (in colour) and grayscale photos

The impact will happen on the side of the planet facing away from Earth. This puts the craft out of contact, and means it will probably carry more than 1,000 unseen images to its final, explosive resting place.

MDIS can take hundreds of photos every day. Earlier this month, mission scientists released fresh images, external which superimposed years of spectrometry data about the chemistry of the planet's surface, illustrated by different colours, onto black-and-white images built up from thousands of smaller MDIS photos.

Proud achievements

The planet has been mapped and studied to a level of detail far beyond the original mission plan. Many of the results themselves have also been surprising.

"A lot of people didn't give this spacecraft much of a chance of even getting to Mercury, let alone going into orbit and then gathering data for four years instead of the original scheduled one-year mission," said William McClintock from the University of Colorado Boulder, principal investigator on MASCS (the Mercury Atmospheric and Surface Composition Spectrometer, another of the seven scientific instruments on board).

"In the end, most of what we considered to be gospel about Mercury turned out to be a little different than we thought."

This is how the BBC News website covered Messenger's launch in 2004

Dr Chabot remembers the tension of processing the first image ever recorded by a spacecraft orbiting Mercury, back in 2011. She had only recently taken over as the instrument scientist on MDIS.

"It was exciting but for me personally it was also a bit stressful," Dr Chabot, who works at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, told the BBC. "But then the first image came back and it looked amazing and beautiful, and we realised we were here at Mercury to stay. I take a lot of pride in that image."

Despite being able to look back with pride, Dr Raines said this is still a sad day for Messenger scientists.

"Pretty much all the instruments are still doing great, so that makes it a little harder," he told BBC News. But the mission was always going to be limited by the fuel needed to maintain its difficult orbit.

"To be honest, I've seen this day coming for a long time and it's just one of these things that I've not been looking forward to. I'm really going to be sad to see it go."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published30 April 2015

- Published17 March 2015

- Published30 March 2015

- Published16 March 2014

- Published16 February 2013

- Published30 November 2012

- Published18 March 2011