LHC smashes energy record with test collisions

- Published

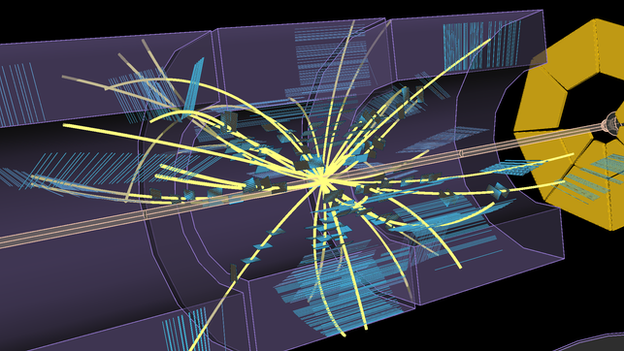

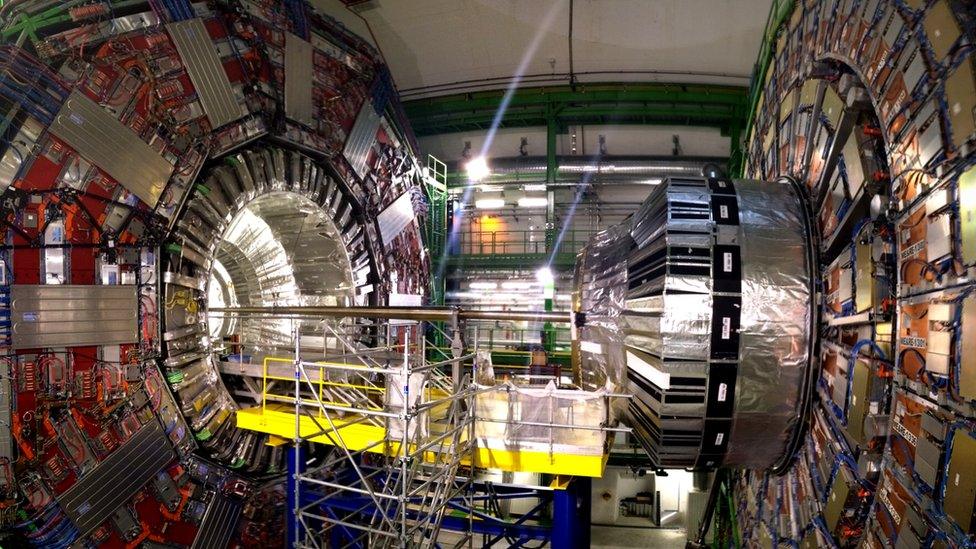

Detectors like these in the CMS experiment will soon be pushing new boundaries for physics

A new record has been set by the Large Hadron Collider: its latest trials have smashed particles with vastly more energy than ever before.

On Wednesday night, two opposing beams of protons were steered into each other at the four collision points spaced around the LHC's tunnel.

The energy of the collisions was 13 trillion electronvolts - dwarfing the eight trillion reached during the LHC's first run, which ended in early 2013.

"Physics collisions" commence in June.

At that point, the beams will contain many more "bunches" of protons: up to 2,800 instead of the one or two currently circulating. And the various experiments will be in full swing, with every possible detector working to try to sniff out all the exotic, unprecedented particles of debris that fly out of proton collisions at these new energies.

For now, however, the collisions are part of the gradual testing process designed to ensure nothing is missed and nothing goes awry when the LHC goes into that full "collision factory" mode.

New territory

"We begin by bringing the beams into collision at 13 TeV (teraelectronvolts), and adjusting their orbits to collide them head-on," said Ronaldus Suykerbuyk from the operations team at Cern - the organisation based near Geneva in Switzerland that runs the LHC.

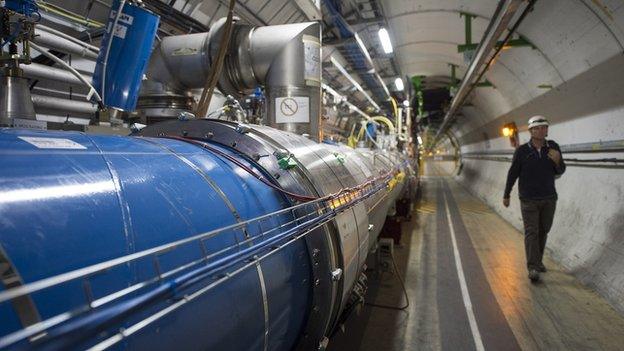

All systems go: Cern's control room allows engineers to monitor all the LHC systems

The huge collider has been through a planned two-year refit, after the conclusion of its first run - which in 2012 produced the first solid evidence for the famous Higgs boson.

So physicists are excited to see the machine winding back up again, although it is an overwhelmingly incremental process.

In early April, after a slight delay, twin proton beams circulated the LHC's 27km ring, 30 storeys below the Swiss-French border, for the first time in two years. This was at a much lower, preliminary energy; five days later the energy reached 6.5 TeV per beam for the first time.

The first collisions followed in early May - again, at a lower, safer energy to begin with. Thursday's collisions are in new territory.

Numbers game

Prof David Newbold, from the University of Bristol, works on the CMS experiment. He said the new energies present new technical challenges.

"When you accelerate the beams, they actually get quite a lot smaller - so the act of actually getting them to collide inside the detectors is really quite an important technical step," Prof Newbold told BBC News.

"13 TeV is a new regime - nobody's been here before."

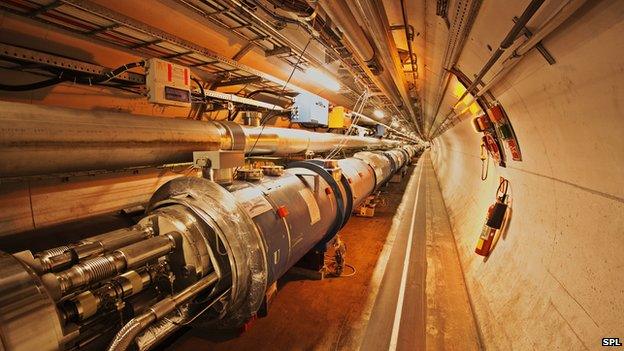

Protons first circulated at the new energies (without collisions) on April 10

Now that collisions are under way, Prof Newbold explained, the engineers in charge of the beams can start to pump in more and more protons.

"The special thing about the LHC is not just the energy we can collide the beams at, it's also the number of collisions per second, which is also higher than any other accelerator in history.

"The reason for that is - like the Higgs boson last time - what we're principally looking for is incredibly rare decay particles. And the more collisions you have per second, the more chance you have of finding something that's statistically significant."

So the build-up that will now unfold, from one or two bunches of protons to thousands, will make even more history. But these early tests are critical to make sure that the 6.5 TeV beams can be steered onto collision course without damaging any of the detectors, or the massive magnets that steer the protons and accelerate them to very near the speed of light.

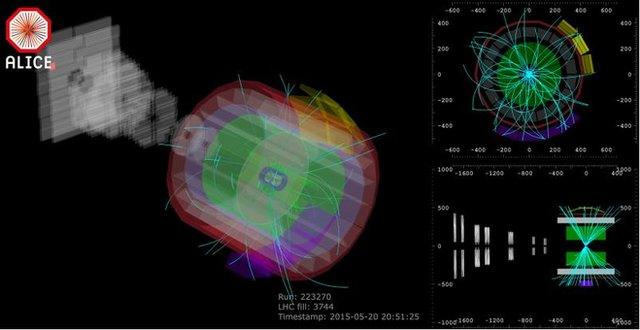

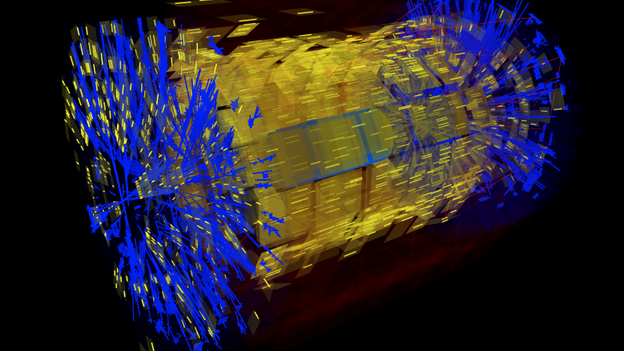

The collisions showered particles onto detectors inside the LHC experiments

Dan Tovey, a physics professor at the University of Sheffield who works on the LHC's Atlas experiment, said the teams were having to "re-learn" how to run their detectors.

"We know how everything worked back in 2012, but a lot has changed since then, both with the machine and with the experiments as well," Prof Tovey told the BBC.

"At this stage it's not telling us anything about new physics. Mainly it's helping us learn about the performance of our experiments."

Come June, however, the data emerging from the LHC will shift the scientific horizon. Researchers hope to tackle big, unanswered questions and push our knowledge beyond the Standard Model of particle physics.

"It's tremendously exciting," Prof Tovey said.

"Individually, we all have the things that we're particularly interested in; there's a variety of new physics models that could show up. But to be honest, we can't say for certain what - if anything - will show up.

"And the best thing that could possibly happen is that we find something that nobody has predicted at all. Something completely new and unexpected, which would set off a fresh programme of research for years to come."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published5 May 2015

- Published5 April 2015

- Published28 March 2015

- Published5 March 2015

- Published31 March 2015

- Published15 February 2015