Rosetta: Comet 67P makes closest approach to Sun

- Published

The comet emitted its brightest jet so far on 29 July

Comet 67P has passed the closest point to the Sun in its 6.5-year orbit, with the European spacecraft Rosetta still in orbit around it.

This landmark, called "perihelion", occurred at 03:03 BST on Thursday, when 67P was 186 million km from the Sun - a distance that puts it between the orbits of Earth and Mars.

The Rosetta team has been studying the small, icy world as it warms up.

It has released dust and gas, including a very bright jet seen on 29 July.

Scientists have also seen a "boulder" - a chunk of the comet nucleus - travelling through space above 67P's surface.

Dramatic images of the dust and gas outburst - the brightest jet seen so far by Rosetta's cameras - were released on Tuesday by the European Space Agency, Esa.

"Usually, the jets are quite faint compared to the nucleus and we need to stretch the contrast of the images to make them visible - but this one is brighter than the nucleus," said Carsten Guettler, a member of the Osiris camera team from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany.

The material released by comets, as they become more active on approach to the Sun, is the reason for their characteristic tails when they appear in the night sky.

This particular jet, caused by frozen ices turning to gas and pouring out into space, was bright and brief. Three photos, each separated by 18 minutes, capture it appearing and fading.

The jet can be seen appearing and fading in these three images, taken at 18 minute intervals

Analysis - David Shukman, Science Editor

Rosetta has a ringside seat at the most interesting phase of a comet's life and the pictures are remarkable. The moment that a bright white jet of gas and dust blasts off the surface is like a scene from science fiction.

The sight of a large boulder hurtling away from the surface is glimpse of what could be the beginning of a process of demolition, a reminder that the whole icy world could split in two. And the sequence showing the comet tumbling through space emitting luminous rays is almost exactly like an animation produced by one of the space agencies some years ago.

The fact that the comet is losing enough water to fill ten Olympic-sized swimming pools every day is a stark illustration of the extraordinary scale of change under way so there's the potential for even more dramatic transformation in the coming weeks and months as the Sun's heat takes effect.

This is a mission that made discoveries even as it approached the comet a year ago. Then the landing of the tiny craft Philae last November, chaotic and not exactly according to plan, yielded even more. And whether that popular but now silent robot wakes up again or not, the orbiting mothership Rosetta is in perfect shape to maintain its watch as the next phase of the adventure begins.

Tumultuous activity like this is not necessarily expected to coincide with perihelion, as any temperature increase is gradual - and also lags behind the comet's actual distance from the Sun.

"The solar flux increase between today, tomorrow and the day after is almost immeasurable," said Mark McCaughrean, senior science advisor at Esa.

He likened the comet's perihelion to the summer solstice, which is not the warmest day of summer on Earth.

"On the Earth there's a thermal lag, and that's true on the comet too. It reaches peak sunlight tomorrow, but it probably doesn't reach peak activity.

"We don't know exactly when that peak will be. Nobody's ever done this before."

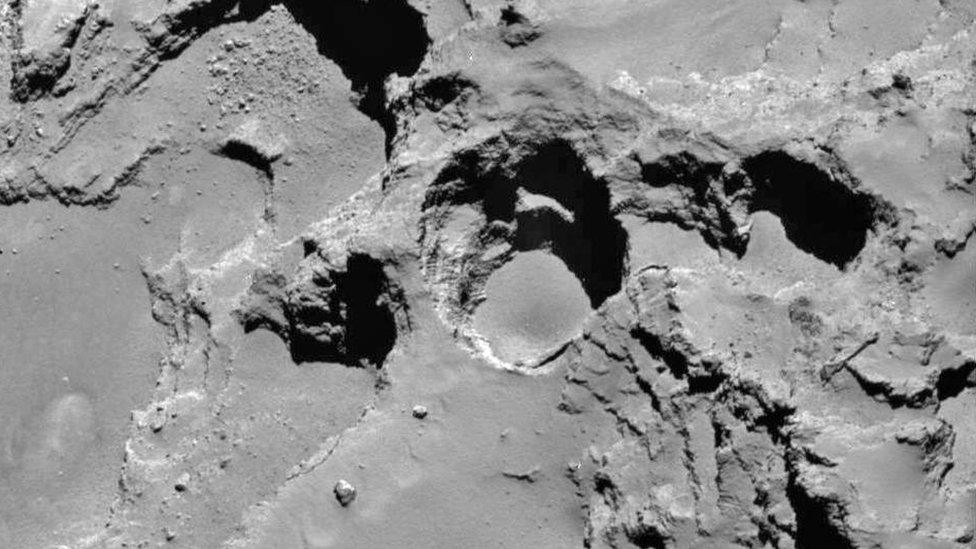

In a Google Hangout, Holger Sierks, principal investigator for Rosetta's Osiris instrument, said of the "boulder" from 67P: "We found the first resolved chunk leaving the nucleus."

"We do not know what the distance to it is. If it's in the plane of the nucleus, it would be about 40m in size. But we have an indication it might be closer to the spacecraft, which would change the size of the chunk we see in our images to something like 1m."

It was just over a year ago, on 6 August 2014, that Rosetta first arrived at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. It has spent the intervening months in orbit, manoeuvring itself as close as 30km to the surface of the duck-shaped "icy dirtball".

In the last few months, increasing flows of dust around the comet have forced the probe to retreat.

"We've now moved back to 300-plus km," Prof McCaughrean said.

"Because activity is building up, we are constantly monitoring the navigation cameras, in case they lose lock. And the engineers are pre-emptively moving the spacecraft further away.

"Activity will build up further after perihelion, so we'll probably move even further away - then wait to go back in again. Probably by the end of the year we'll be back down at 10-30km. At that point, we get to see what's changed."

Rosetta arrived at Comet 67P in August 2014

The Philae lander, meanwhile, is still on the comet's surface, but not communicating.

After Rosetta dropped it onto the comet in November 2014, its historic but wayward landing finished in the shade, making it difficult for Philae's solar panels to charge its batteries.

It has only briefly "phoned home" again since, and controllers are unsure if they will ever regain a stable line of communication between Rosetta and its slumbering lander.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published30 July 2015

- Published1 July 2015

- Published19 June 2015

- Published14 April 2015