Who owns outer space?

- Published

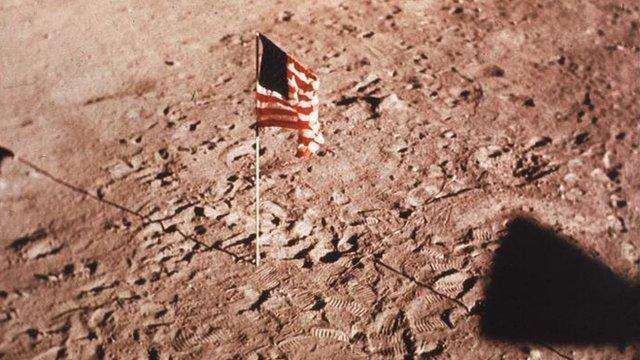

The US flag was planted on the Moon in 1969, two years after the Outer Space Treaty was created

When space crops up in conversation, ownership does not immediately spring to mind. But as the human race continues to advance in this field, and with commercial space enterprises just around the corner, questions about power politics and their interaction with space exploration must be asked and answered.

Neil Armstrong famously planted a US flag on the Moon in 1969. This gesture may have implied territorial ownership, but was purely symbolic because of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty.

129 countries, including China, Russia, the UK and the US, have committed to this treaty, which is overseen by the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, external.

It sets out important principles, such as the concept that space should be considered the province of all mankind, that outer space is free for the exploration and use by all states, and that the Moon and other celestial bodies cannot be claimed by a sovereign nation state. Additionally, the Moon and celestial bodies are to be used purely for peaceful purposes, and weapons will not be placed in orbit or in space.

"This is frequently referred to as the outer space constitution," says Dr Jill Stuart, a visiting fellow at the London School of Economics and Editor of the journal Space Policy. She spoke to BBC News at the British Science Festival, external in Bradford.

Where is outer space?

This treaty has worked so far, but there are some potential pitfalls - as Dr Stuart explains.

"There is no official definition of outer space, but it's something on which a United Nations working group is currently consulting member states. I suspect we will settle for a physical demarcation at the Karman Line, which is about 100km up, but it's also an option to go for a functional definition. This is where laws are defined based on the function of a space object rather than where it is in space."

A physical demarcation results in a lot of paperwork for commercial spaceflight companies, such as Virgin Galactic, which is developing a sub-orbital tourist space plane. It means Virgin has to abide by both international aviation laws as well as space laws, despite only being "in space" for five or six minutes. A sensible compromise has to be reached.

Mining the Moon

Commentators agree that the Outer Space Treaty is an excellent foundation for international space law, but it makes no reference to commercial space activities, such as the exploitation of space resources; presumably because this was not foreseen back in 1967.

"International law is ambiguous about private companies setting up mining operations in space. There is a strong case for revisiting the Outer Space Treaty to bring it up to date," argued Ian Crawford, a professor of planetary science at Birkbeck College, University of London.

There is an argument that in the future, when assets are developed in space, it is more cost-effective to use raw materials mined from space rather than transporting them from Earth.

Will the era of commercial spaceflight change our attitude to space ownership?

There is also another strong reason for developing clearly defined space laws, says Prof Crawford: "For scientific reasons, some areas of the Moon are sites of special scientific interest and should be preserved and protected from commercial activities."

As the Earth's population grows and more raw materials are required to maintain high living standards, it is arguably more ethical and environmentally sensitive to mine those materials from celestial bodies with no existing habitats and no bio-diversity to disrupt - as opposed to continuing to over-exploit this planet.

This raises a further issue: if space mining does become a reality through private companies like Planetary Resources and Moon Express, does their work contradict the Outer Space Treaty? Can they justify that they are doing this for the benefit and interest of all countries and mankind?

Space wars

"Our daily lives depend on space. Every time you make a phone call, financial transaction or use Google Maps - it is dependent on satellite signals. In times of conflict, it would be easy to target those satellites. Space has the potential to be the new battlefield," said Dr Cassandra Steer, executive director at the McGill Institute for Air and Space Law.

Despite the myth that outer space is a lawless "wild west", in fact all of international law applies there.

So, if these laws already apply, what's the problem?

Sovereign territory: each country owns its own satellites

As well as the Outer Space Treaty, there are four other treaties governing space law. According to the Liability Convention, anything that goes into space must be registered with its launching state, and becomes sovereign territory.

"If you were to target another country's satellites, you will create a lot of space debris, which could impact other satellites," said Dr Steer. This is where ambiguity arises over who is responsible for clearing up the mess.

Dr Steer added that some satellites have dual use. Their technologies can be used in the military as well as the civilian context - and this makes the issues around the Outer Space Treaty quite complex.

What if other intelligent life is encountered, with their own set of rules? Whose laws take precedence? This topic perhaps throws up more questions than solutions.

"We're at a point in time where it's ever-more pressing to re-evaluate our current legal infrastructure that governs outer space," Dr Stuart concluded.

- Published10 September 2015

- Published7 March 2013

- Published26 March 2012

- Published16 January 2012