Sentinel satellite pictures a 'clear skies' Africa

- Published

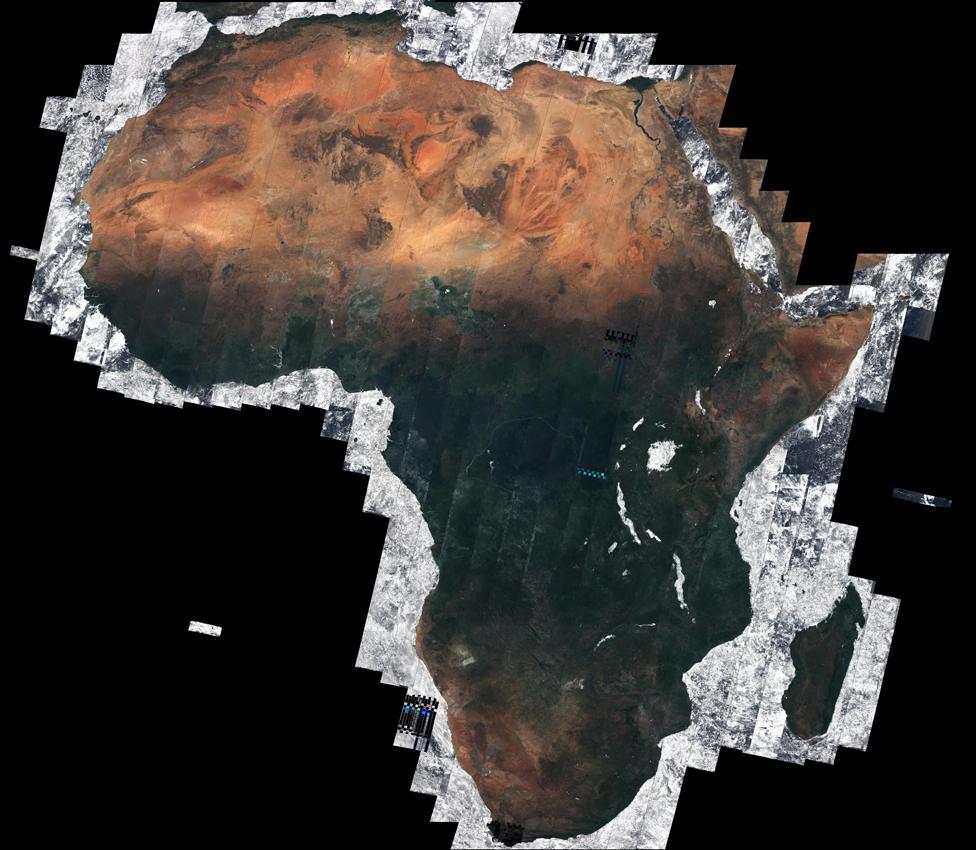

Cloud-free Africa. The full-sized image represents 32 terabytes of data

Africa undressed: the continent pictured with no clouds in the sky.

This is not a natural state, of course; there is always a weather system bubbling up somewhere.

But if you have access to a lot of images acquired over the course of several months, it becomes possible to construct a mosaic.

This one was produced from observations made by the EU's new Sentinel-2a satellite, external, which is now routinely mapping Planet Earth.

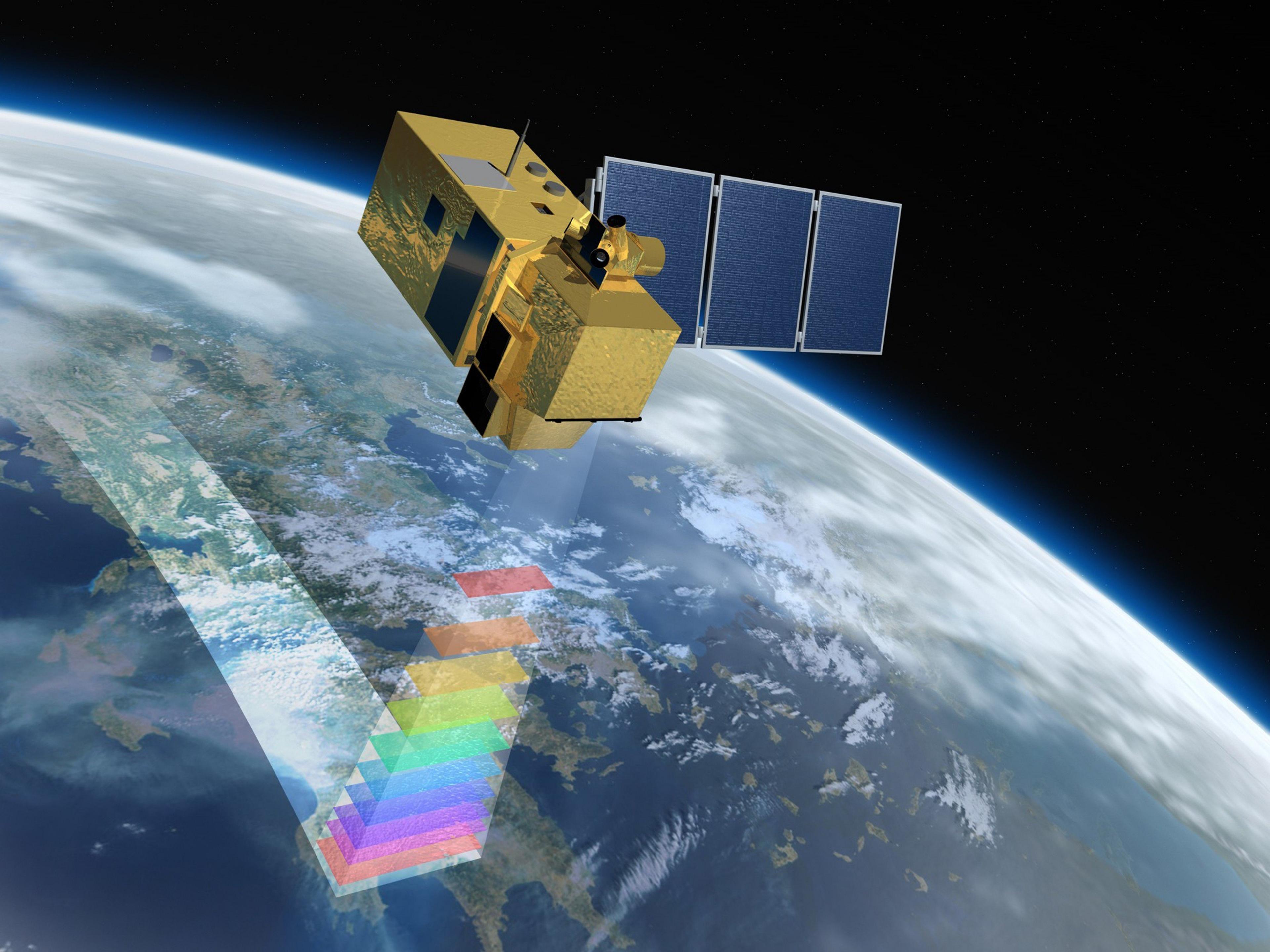

It is a powerful capability. Sensitive across 13 spectral bands (colours) and able to see details as small as 10m across - the spacecraft's camera "carpet maps" the land surface beneath it. Every strip is 290km wide.

And if you think about how fast the satellite is moving in orbit - that is a large swathe of real estate to scoop up at once.

It means, for example, that for an elongated country like Norway, it is possible to capture almost its entire territory in just one pass. Some 290,000km2 in just four minutes. Half of Spain can be done in two minutes.

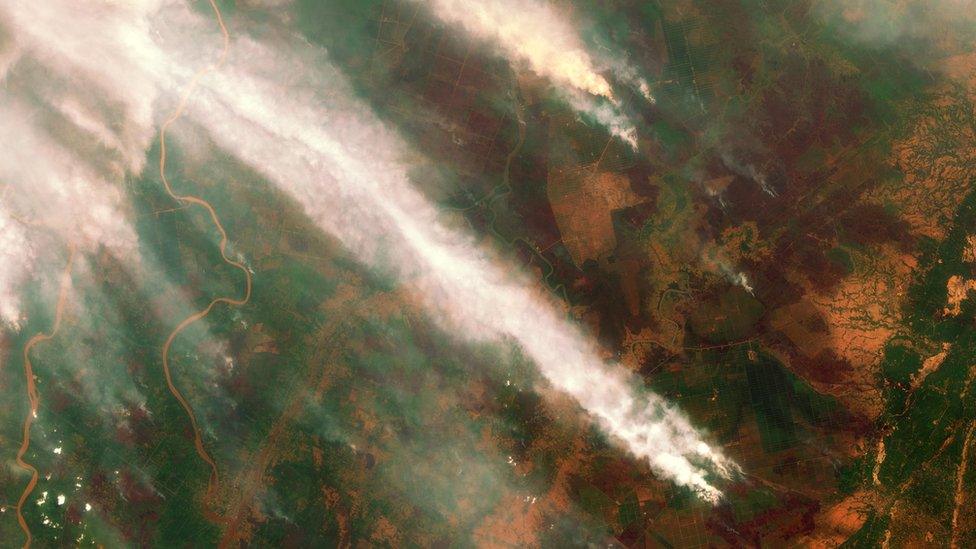

The Sentinel's free and open data is being used for all manner of applications - from urban planning and crop monitoring to climate studies and biodiversity assessments.

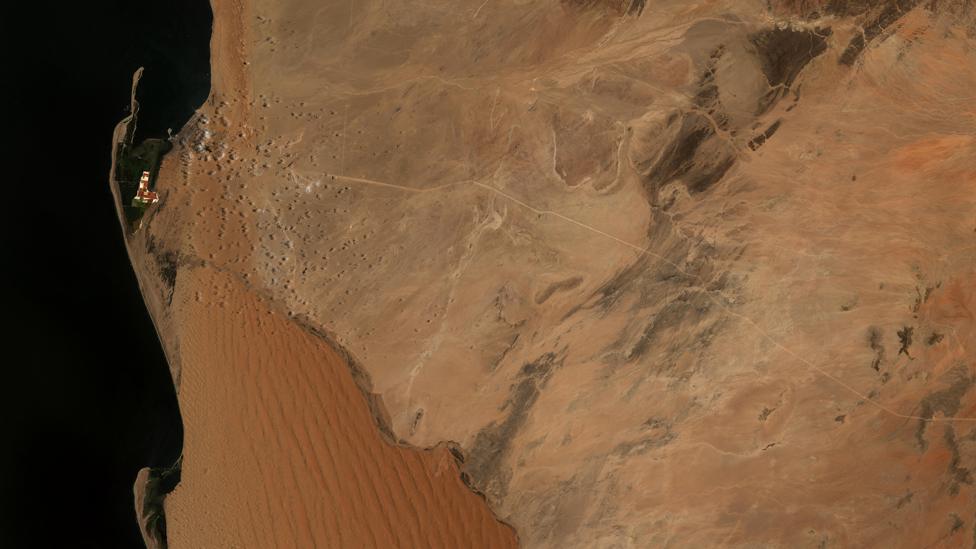

Climate studies: Walvis Bay, Namibia, is one of the driest cities in the world, with an annual precipitation of less than 10mm

Cloud is the enemy, though. Although the Sentinel's colour camera can remove light clouds like cirrus, a thick deck is impenetrable. And for tropical regions, this is a significant issue.

"We have many orbit segments going from Norway down to the Sahara with only marginal clouds. But when it comes to the tropics, such acquisitions get rare," explained Dr Bianca Hoersch, the European Space Agency's (Esa) mission manager on Sentinel-2a.

"For this Africa composite, the Climate Change Initiative team, external took for the tropical part any useful orbit segment, going down to single cloud-free pixel selection, from any data acquired between August 2015 and April 2016."

The full image contains 32 terabytes of data.

The pivot-centre irrigation fields of Sharq Al-Owainat: Agricultural monitoring is a key application

Only the African Great Lakes, including Victoria and Tanganyika, have been left in a cloudy state. That said, there are Sentinel-2 scientists who are just as keen to get clear views of inland and coastal water bodies, to track sediment flows, algal blooms, pollution incidents, and the like.

The interest in the data was evident at last week's Esa Living Planet Symposium, external. Many of the sessions dedicated to the satellite's work were standing room only.

The spacecraft is not quite working to full capacity. It is still in the ramp-up phase following its launch last June.

It has just gone to mapping every part of the Earth's land surface (cloud or no cloud) at least once every 20 days, and hopes to get that down to every 10 days by the end of the year (Europe and Africa are already mapped at this rate). A new X-band radio ground station is being made available to downlink the additional data volume. Some of it will also be sped to Earth via a laser link.

Lake Malawi: There are many scientists who will use Sentinel-2a data to study water bodies

In a year's time, Sentinel-2a will be joined in orbit by a sister platform, Sentinel-2b. This second platform will permit a re-visit time of just five days - making it much easier to achieve those cloud-free segments.

Looking even further to the future, the EU is determined the imaging capability should be available deep into this century and has asked Esa already to procure an additional pair of satellites, Sentinels 2c and 2d.

"Those two spacecraft will potentially be available to launch in 2020 and 2021," said Sentinel-2 project manager François Spoto.

"The concept is not to have four spacecraft in orbit, but it will create enough spacecraft assets to replenish the constellation if and when required."

Sentinel-2: The business of making maps

Sentinel-2 maps the land surface in 290km-wide strips

Agriculture: Gathering crop statistics and yield assessments

Urban: Planning city-wide infrastructure improvements

Forests: Checking de- or re-forested areas for treaty purposes

Biodiversity: Understanding the habitats where wildlife exist

Health: Tracking conditions associated with disease spread

Water: Evaluating water body extents for flood assessments

Disaster: Making damage maps following major earthquakes

Cryosphere: Mapping snow fields and glacier melting

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published3 December 2015

- Published28 July 2015

- Published23 June 2015

- Published2 April 2014

- Published3 April 2014

- Published25 February 2015