Cassini probe heads towards Saturn 'grand finale'

- Published

Earl Maize: "We can't leave Cassini in an uncontrolled orbit near Saturn"

Cassini has used a gravitational slingshot around Saturn's moon Titan to put it on a path towards destruction.

Saturday's flyby swept the probe into an orbit that takes it in between the planet's rings and its atmosphere.

This gap-run gives the satellite the chance finally to work out the length of a day on Saturn, and to determine the age of its stunning rings.

But the manoeuvre means also that it cannot escape a fiery plunge into Saturn's clouds in September.

The US space agency (Nasa) is calling an end to 12 years of exploration and discovery at Saturn because the probe's propellant tanks are all but empty.

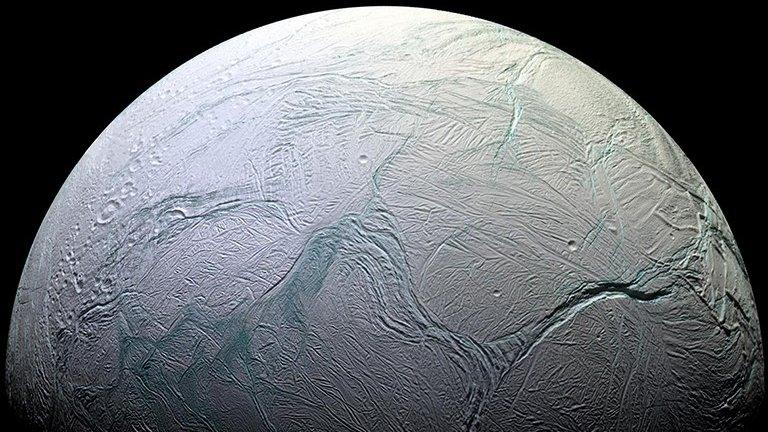

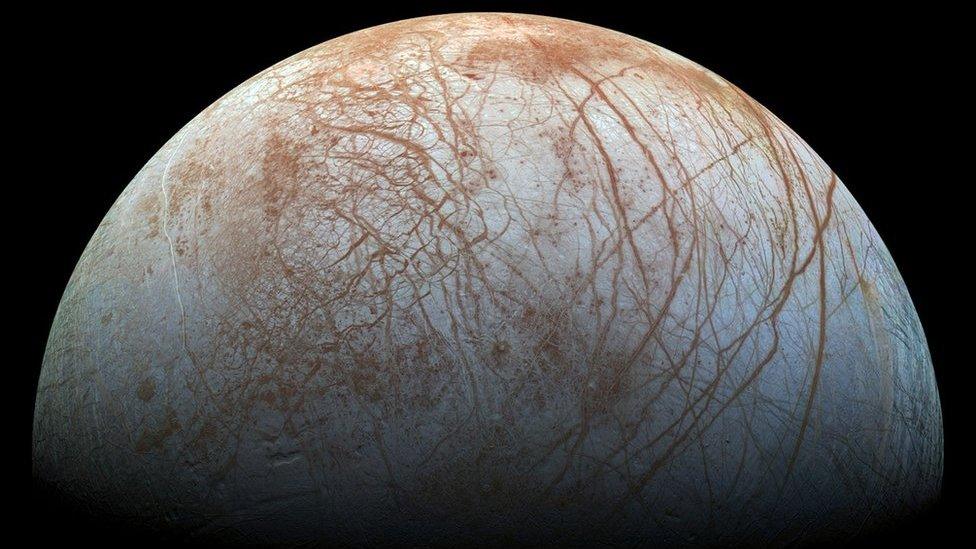

Controllers cannot risk an unresponsive satellite one day crashing into - and contaminating - the gas giant's potentially life-supporting moons, and so they have opted for a strategy that guarantees safe disposal.

"If Cassini, external runs out of fuel it would be uncontrolled and the possibility that it could crash-land on the moons of Titan and/or Enceladus are unacceptably high," said Dr Earl Maize, Nasa's Cassini programme manager.

"We could put it into a very long orbit far from Saturn but the science return from that would be nowhere near as good as what we're about to do," he told BBC News.

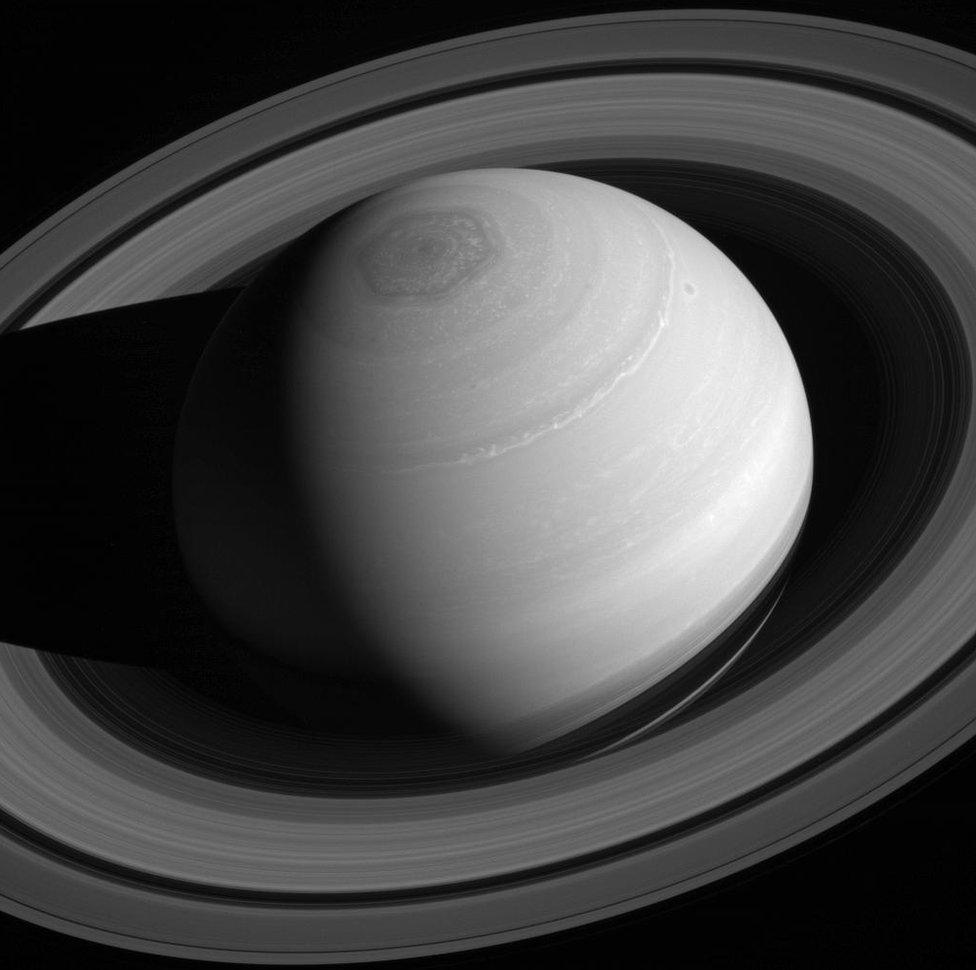

The remainder of the mission will see Cassini repeatedly dive between the atmosphere and the rings

Cassini has routinely used the strong gravitational field of Titan to adjust its trajectory.

In the years that it has been studying the Saturnian system, the probe has flown by the haze-shrouded world on 126 occasions - each time getting a kick that bends it towards a new region of interest.

And on Saturday, Cassini pulled on the gravitational "elastic band" one last time, to shift from an orbit that grazes the outer edge of Saturn's main ring system to a flight path that skims the inner edge and puts it less than 3,000km above the planet's cloud tops.

The probe will make the first of these gap runs next Wednesday, repeating the dive every six and a half days through to its death plunge, scheduled to occur at about 10:45 GMT on 15 September.

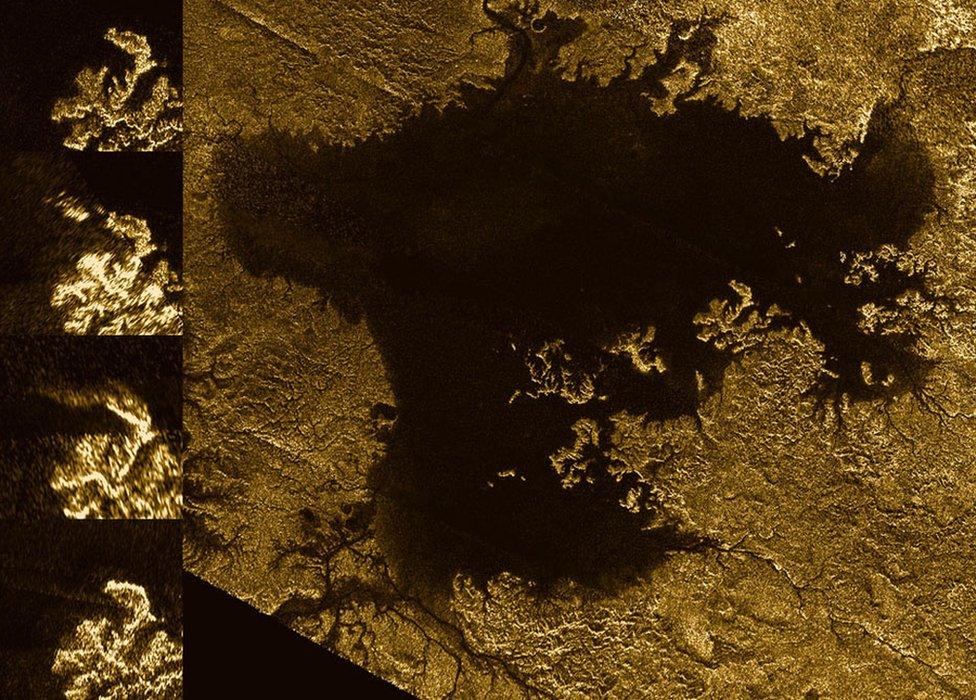

The lakes and seas of Titan contain methane, ethane and other liquid hydrocarbons

Scientists used Saturday's pass of Titan to make some final close-up observations of the moon.

This extraordinary world is dominated at northern latitudes by great lakes and seas of liquid methane.

Cassini's radar was commanded once again to scan their depths and look for what have become known as "magic islands" - locations where nitrogen gas bubbles up from below to produce a transient bumpiness on the liquid surfaces.

This is a bitter-sweet moment for scientists. Titan has yielded so many discoveries, and although the probe will continue to encounter the moon in the coming months, it will never again get so close - less than 1,000km from ground level.

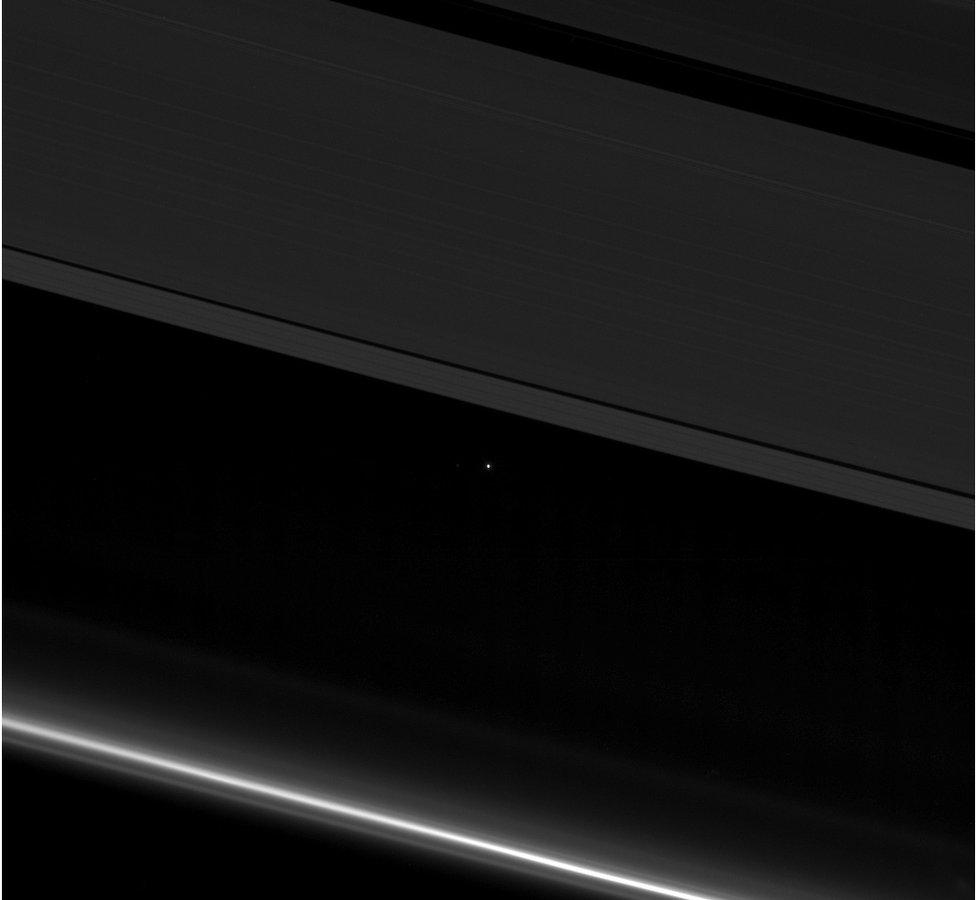

Home: Cassini has just taken this picture of Earth - a bright speck more than one billion km away

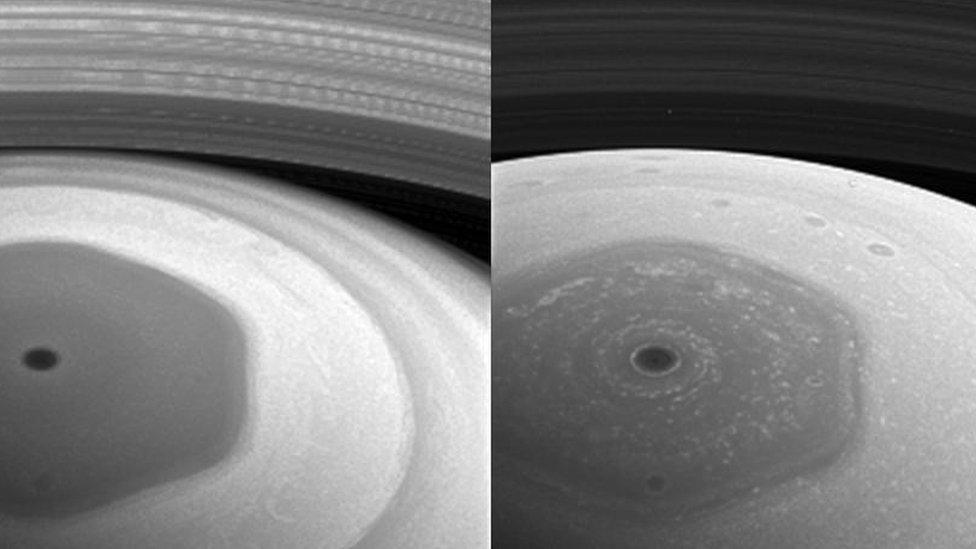

On the other hand, researchers have the prospect now of at last answering some thorny questions at Saturn itself.

These include the length of a day on the planet. Cassini so far has not been able to determine precisely the gas giant's internal rotation period.

From the close-in vantage afforded by the new orbit, this detail should become apparent.

"We sort of know; it's about 10.5 hours," said Prof Michele Dougherty, the Cassini magnetometer principal investigator from Imperial College, London, UK.

"Depending on whether you're looking in the northern hemisphere or the southern hemisphere - it changes. And depending on whether you're looking in the summer or winter seasons - it changes as well.

"So, there's clearly some atmospheric signal which we're measuring that's linked to weather and the seasons that's masking the interior of the planet," she told the BBC.

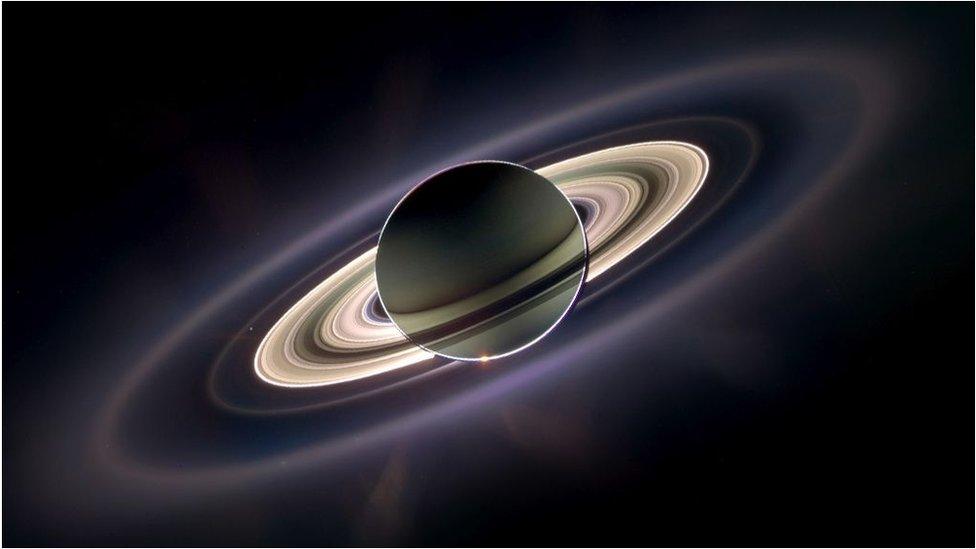

Artwork: Cassini will be destroyed when it plunges into the atmosphere of Saturn

The other major outstanding question is the age of Saturn's rings.

By getting inside them, Cassini will be able to weigh the great bands of ice particles.

"If the rings are a lot more massive than we expect, perhaps they're old - as old as Saturn itself; and they've been massive enough to survive the micrometeoroid bombardment and erosion and leave us with the rings we see today," conjectured Nasa project scientist Dr Linda Spilker.

"On the other hand, if the rings are less massive - they're very young, maybe forming as little as 100 million years ago.

"Maybe a comet or a moon got too close, got torn apart by Saturn's gravity and that's how we have the rings we see today."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published13 April 2017

- Published24 March 2017

- Published13 January 2017

- Published11 December 2015

- Published7 December 2016

- Published30 November 2016