Bloodhound Diary: Staying on course

- Published

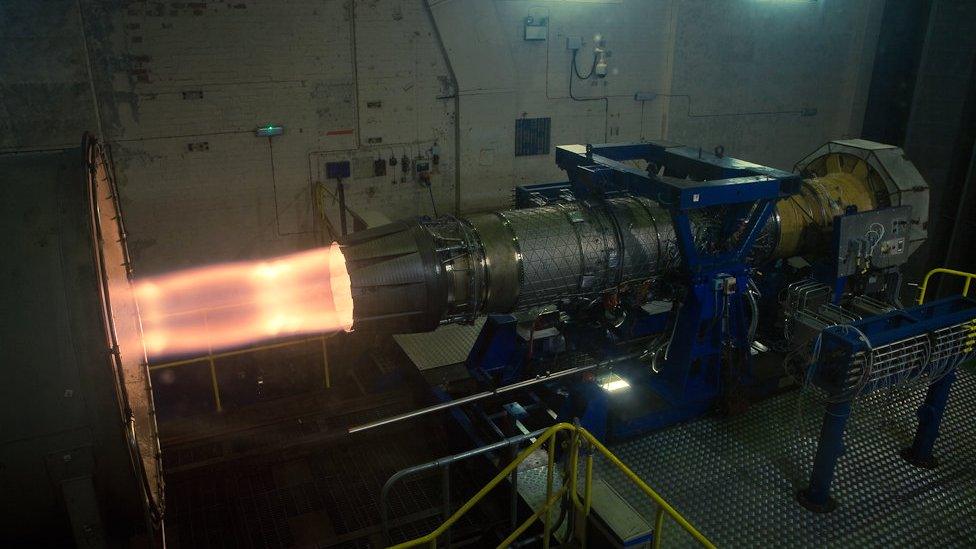

A British team is developing a car that will be capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h). Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the vehicle will first mount an assault on the world land speed record (763mph; 1,228km/h). Bloodhound, external should start running on Hakskeen Pan in Northern Cape, South Africa, in 2018.

Work continues as we prepare Bloodhound SSC to run at Newquay later on this year.

While it's tempting to become frustrated about how long this is taking, a recent comment by an independent project management company put it in perspective for me.

They observed that getting to 1,000mph is "right at the limit of human technical achievement", which tells me two things.

The first is that we've probably chosen the right target for our "Engineering Adventure" to showcase cutting-edge technology to a global audience.

The second is that going to the limit of human achievement is supposed to take time - at least if you're going to do it properly!

One of the key bits of work recently has been the installation and testing of Bloodhound's power-steering system.

This raises a wider question about why you need steering at all, if you're only driving in straight line?

Testing the Steering

The great Malcolm Campbell once described driving along Daytona Beach, back in 1933, as follows: "I had one hell of a job keeping the car on course".

At 272mph, Campbell was doing just over a quarter of Bloodhound SSC's planned top speed.

More recently, while we were busy setting the current supersonic world record in Thrust SSC, I found things similarly challenging, with up to 90 degrees of steering lock required at over 600mph. So, when it comes to Bloodhound, we're not taking anything for granted.

If you want more detail on the difficulties of high-speed steering, have a look at "How hard can it be to drive in a straight line?, external".

The steering has to cope with surface irregularities (which may look small, but feel big at supersonic speeds) and the effect of cross-winds, which are a fact of life on record-breaking tracks that are many miles long.

The car's aerodynamic performance and stability will also play a huge part.

This is why Thrust SSC was such a handful back in 1997, before the technology really existed to understand the likely effects of trying to drive supersonic.

Even with the incredible sophistication of Bloodhound's technology, it's a reasonable assumption that at some point we're going to need to work at keeping the car straight.

The steering is (obviously) a key piece of safety equipment, so it's designed to be as simple and reliable as possible.

We're using a mechanical rack-and-pinion system, where the steering column turns a gear wheel (or "pinion") that drives a toothed rod (or "rack") back and forth to steer the front wheels.

This is the system that just about every road car in the world uses, so it's well-proven.

The Business End

There are, of course, a few differences between a "normal" road car and steering Bloodhound SSC.

The mass of the car, for instance - fully-fuelled, Bloodhound SSC is likely to weigh in at about eight tonnes.

Then there's the size of the wheels, which at 90cm (about 3ft) in diameter are not exactly small.

The wheels are also heavy (about 100kg each) and will rotate at up to 10,000 revs/minute. That will produce some large gyroscopic loads - if you haven't experienced this, then grab a bicycle, lift the front wheel off the ground, spin the wheel as fast as you can and then turn the handle bars - you'll find the bike's steering has become quite stiff.

Multiply that effect by a large number and something similar happens in a land speed record car.

As well as the gyroscopic forces, the car's front wheels will be travelling at supersonic speeds over the ground, which will create some significant "rolling resistance" (surface drag) forces.

All of these forces will be changing continuously as the car runs.

The net result will be, well, so complex that we can't really predict it precisely, but it's a safe bet that the suspension is going to see some big loads.

This is likely to make the steering very heavy at times, which is where the power assistance comes in.

It's not that I can't steer the car using the mechanical system alone, but the power-assistance will make it physically easier and, therefore, should help to make it more precise. At 1,000mph, that's a good thing.

The power assistance is an electrical system, which is run from the "essential services" battery.

Still Testing

This is an aircrew term (I haven't got the rest of the team using it yet, but leave it with me) for the key things that you need to work, even if you have a power failure elsewhere.

From my point of view as the driver, "essential services" are the steering, the radio, the Rolex back-up speedo and the fire systems.

These will have their own separate electrical supply, to make them as reliable as possible.

If the worst does happen and we (somehow) have a total power failure, then the mechanical steering will still allow me to stop the car safely from any speed, even without power assistance.

The other thing that power assistance could offer is some form of automated steering, or computer stabilisation at high speeds.

However, we will definitely not be doing this, for a couple of very good reasons.

The first is that the rules do not allow it, and quite right too in my opinion.

In order to be a "land vehicle" in LSR terms, the FIA rules, external require that the vehicle is "wholly and continuously controlled by the driver".

Even if the rules did allow for a computer stabilisation system, should we really be running a car that needs a computer system (which will be untested in this prototype vehicle) to keep it safe? And if we don't need it, then why fit it?

As previously mentioned, we've already got plenty of things to do.

While we're getting the car ready to run, this year's schools' rocket car competition is coming to a climax.

As you read this, the last of the regional finals have just finished, with the national final planned for Santa Pod Raceway in June.

I'm delighted to say that the Army (and more recently the RAF) have been supporting the competition, helping thousands of young students to experience the excitement of doing engineering and science for themselves.

3, 2, 1, Go… Go!

I probably shouldn't do this, but I have to tell someone about the "race off" between the RAF and the Army at the RAF Leeming regional finals, as it made me laugh so hard.

The video speaks for itself, external, the Army car is the second one to start moving. Apologies to my Army colleagues, but I just couldn't resist.

Back to being sensible for a moment. I was down in the Bloodhound Technical Centre this week for one of our regular planning meetings, where we started to look at dates for UK runway runs at Newquay later this year. I know that a lot of people really want to be there but no, sorry, I can't give you a hint. We'll release the date(s) as soon as we can, so you can come to see Bloodhound run for the first time in the UK.

While we were in the meeting, a video conference was going on by our full-size "Show Car".

Global Bloodhound

The thing that really surprised me is that the video link was with a US school in Ohio.

More surprising still was to learn that we've supplied around 1,500 model rocket car kits to American schools recently.

Our "global Adventure" really is going global.

If you have a couple of minutes to spare, have a look at the video from Hudson City School District, Ohio, external.

It's been put together by one of our sponsors, Swagelok, and it's lovely.

My highlight is the teacher talking about a class discussion on Bloodhound: "We had a phenomenal discussion; they talked about things that just blew my mind."

If it's having that effect on the teacher, just think about how this is grabbing the kids' attention. I love this project.

This month's "May Day Extravaganza" at the Bloodhound Technical Centre gave a huge audience the chance to see the latest work on the car, plus some new (and unusual) Bloodhound-related competitions.

The kids' "make a vegetable Bloodhound car" competition produced some real bits of art.

I'll leave you with a couple of the winning submissions, including the epically named "SPUDHOUND SSC". Nice work.

- Published24 March 2017

- Published6 February 2017

- Published14 December 2016

- Published8 November 2016

- Published13 October 2016

- Published26 September 2016

- Published29 July 2016