Gravitational waves: Third detection of deep space warping

- Published

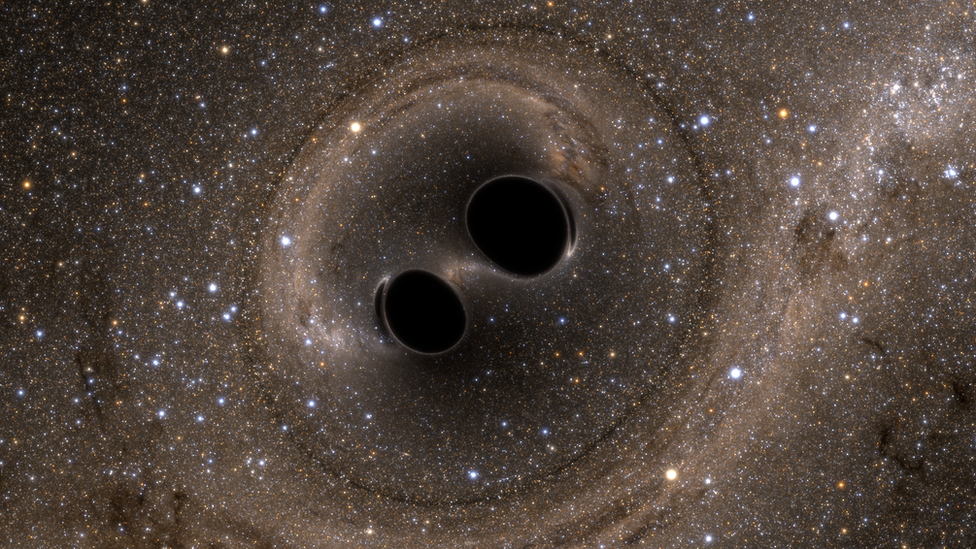

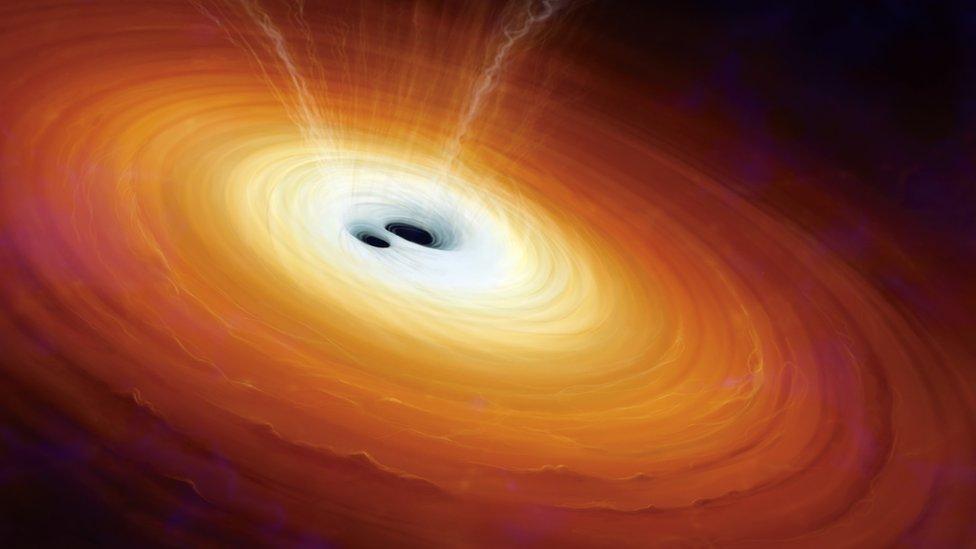

Artwork: Two coalescing black holes spinning in a non-aligned fashion

Scientists are reporting yet another burst of gravitational waves.

The signals were picked up by the Advanced LIGO, external facilities in the US and are determined to have come from the merger of two huge black holes some three billion light-years from Earth.

It is the third time now that the labs' laser instruments have been perturbed by the warping of space-time.

The detection confirms that a new era in the investigation of the cosmos is now truly under way.

"The key thing to take away from this third, highly confident event is that we're really moving from novelty to new observational science - a new astronomy of gravitational waves," said David Shoemaker, spokesperson for the LIGO Scientific Collaboration.

The latest detection, which was made at 10:11 GMT on 4 January, is described in a paper accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review Letters, external.

Five reasons why gravitational waves matter

Once again, it is a merger of black holes, and once again the energy scales involved are extraordinary.

The analysis suggests the two black holes that coalesced had starting masses that were just over 31 times and 19 times that of our Sun. And when they finally came together, they produced a single object of a little under 49 solar masses.

It means the unison radiated a simply colossal quantity of pure energy.

"These are the most powerful astronomical events witnessed by human beings," explained Michael Landry, from the LIGO lab in Hanford, Washington State, external.

"In this case two times the mass of the Sun were converted into deformations in the shape of space. This energy is released in a very short space of time, and none of this comes out as light which is why you have to have gravitational wave detectors."

Gravitational waves - Ripples in the fabric of space-time

A computer simulation of gravitational waves radiating from two merging black holes

Gravitational waves are a prediction of the Theory of General Relativity

It took decades to develop the technology to directly detect them

They are ripples in the fabric of space-time generated by violent events

Accelerating masses produce waves that propagate at the speed of light

Detectable sources should include merging black holes and neutron stars

LIGO fires lasers into long, L-shaped tunnels; the waves disturb the light

Detecting the waves opens the cosmos to completely new investigations

As with the two previous observations - in September and December 2015 - the scientists are uncertain about where on the sky the 4 January event occurred. From the three millisecond gap between the signal being picked up first at Hanford and then at the second lab in Livingston, Louisiana, external, researchers can only specify a large arc of possibility for the source.

Conventional telescopes were alerted to go look for a coincident flash of light, but they saw nothing that could be confidently ascribed to the black hole merger.

The LIGO collaboration will only solve this triangulation problem when a third station called VIRGO, in Italy's Pisa province, external, starts work alongside the US pair this summer.

'Every 15 minutes'

The detection of gravitational waves has been described as one of the most important physics breakthroughs in recent decades.

Being able to sense the distortions in space-time that occur as a result of cataclysmic events represents a transformative step in the study of the Universe, one that does not depend on sensing electromagnetic radiation in any of its forms - from radio and optical light through to X-rays and gamma rays. Now, as well as trying to "see" far-off events, scientists can also "listen" to those events as they vibrate the very fabric of the cosmos.

And immediately this approach is telling researchers new things. One simple discovery is the recognition of a totally new class of black holes. Before LIGO's discoveries, orbiting pairs of these objects, some of 25 solar masses and greater, were completely unknown.

"In two years, we've gone from not knowing these systems existed to being really confident there's a whole population of them out there," commented Sheila Rowan, a collaboration team member from Glasgow University, UK. "And it's all consistent with gravitational waves from one of these systems passing through us about once every 15 minutes, from somewhere in the Universe," she told BBC News. The quest for the future is to get LIGO to sensitivities where more of these events can be detected.

Unbroken Einstein

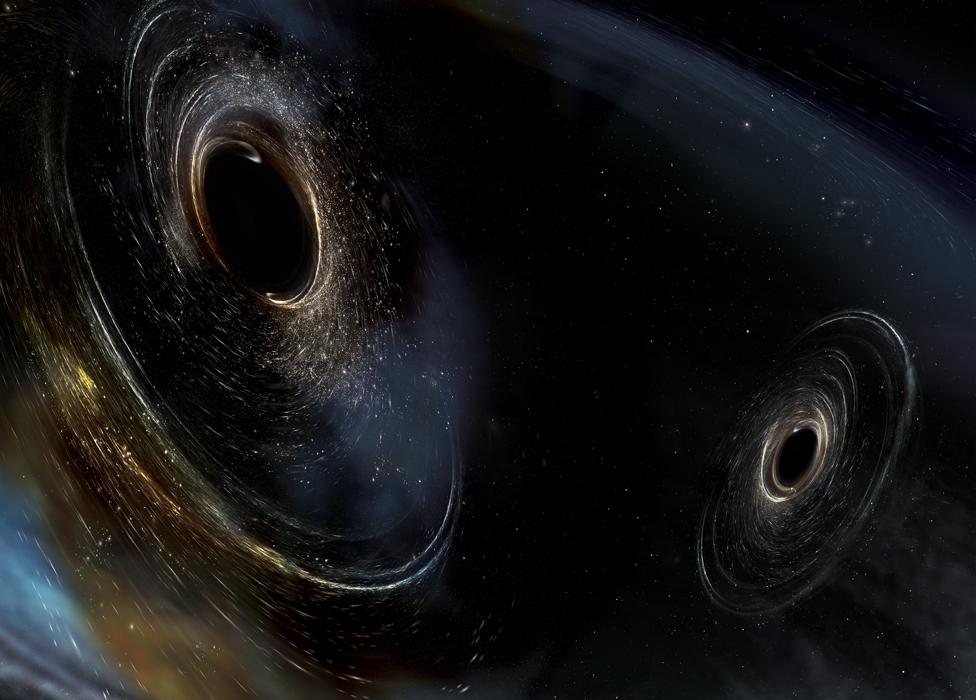

Also possible now are new investigations of the properties of black holes. The scientists can tell from the nature of the 4 January signal that the spins of the objects were not fully aligned when they came together.

This suggests they were not created from a pair of previously orbiting stars that exploded and then collapsed into black holes. Rather, their origin was more probably as stars that led independent lives and only at some end stage fell in as a duo.

"In that first case, we would expect that the spins would stay aligned," said Laura Cadonati, the collaboration's deputy spokesperson. "So, we have found a new tile to put in the puzzle of understanding formation mechanisms."

In addition, gravitational wave astronomy permits new tests of Einstein's theories. Because of the greater distance to this merger (twice the distance to the 2015 events), researchers could more easily look for an effect called "dispersion".

For light, this describes how electromagnetic radiation of different frequencies will travel at different speeds through a physical medium - to produce a rainbow in a glass prism, for example.

Einstein's general theory of relativity forbids any dispersion from happening in gravitational waves as they move out from their source through space towards Earth.

"Our measurements are really very sensitive to minute differences in the speeds of different frequencies but we did not discover any dispersion, once again failing to prove that Einstein was wrong," explained Bangalore Sathyaprakash, a LIGO team member from Penn State, US, and Cardiff University, UK.

Hanford lab: Some of the big questions in science now require big machines to answer them

In a poignant coincidence, 4 January was also the day that Heinz Billing, a pioneer of gravitational wave science, died aged 102, external.

The German physicist and computer expert built one of the first laser interferometers - the instruments now used to detect gravitational waves. His early work is credited with making crucial contributions to the development of the eventual LIGO systems.

"His group started in about 1975, just before we did it here in Glasgow," recalled LIGO collaborator Jim Hough. "They were following the idea that the American Rai Weiss had had of using multiple beam delay lines, and of course the German detector was absolutely superb. They did fabulous work that has continued in Germany to this day."

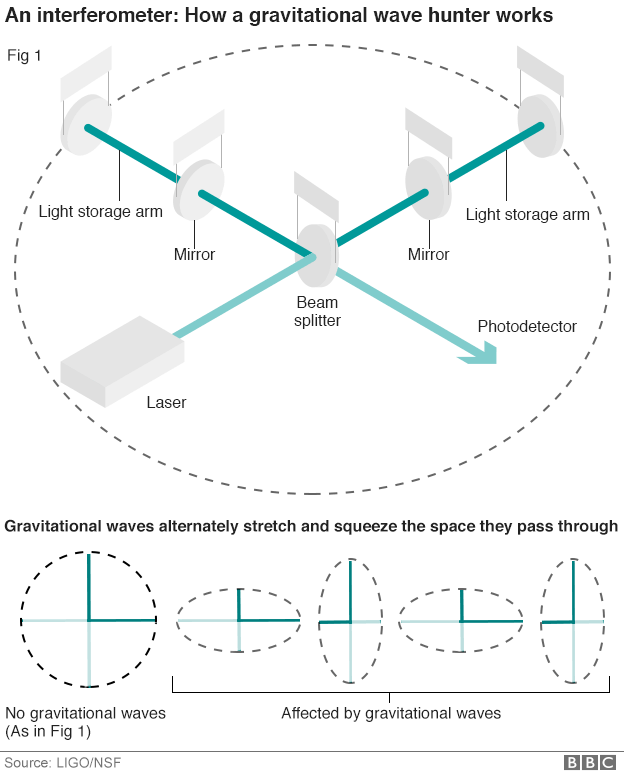

A laser is fed into the machine and its beam is split along two paths

The separate paths bounce back and forth between damped mirrors

Eventually, the two beams are recombined and sent to a detector

Gravitational waves passing through the lab should disturb the set-up

Theory holds they should very subtly stretch and squeeze its space

This ought to show itself as a change in the lengths of the light arms

The photodetector captures this signal in the recombined beams

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published8 March 2017

- Published18 February 2017

- Published15 June 2016

- Published12 February 2016

- Published11 February 2016