Asteroid impact plunged dinosaurs into catastrophic 'winter'

- Published

Artwork: The impact hit with the energy equivalent to 10 billion Hiroshima bombs

Scientists say they now have a much clearer picture of the climate catastrophe that followed the asteroid impact on Earth 66 million years ago.

The event is blamed for the demise of three-quarters of plant and animal species, including the dinosaurs.

The researchers' investigations suggest the impact threw more than 300 billion tonnes of sulphur into the atmosphere.

This would have dropped average global temperatures below freezing for several years.

Ocean temperatures could have been affected for centuries. The abrupt change explains why so many species struggled to survive.

"We always thought there was this global winter but with these new, tighter constraints, we can be much more sure about what happened," Prof Joanna Morgan, from Imperial College London, told BBC News.

The new assessment is reported in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, external.

The drill project is revealing new insights on one of the most astonishing events in Earth history

The UK geophysicist was the co-lead investigator on the 2016 project to drill into what remains of the impactor's crater under the Gulf of Mexico.

She and colleagues spent several weeks retrieving the rock samples that would allow them to reconstruct precisely how the Earth reacted to being punched by a high-velocity space object.

Their study suggests the asteroid approached the surface from the north-east, striking what was then a shallow sea at an oblique angle of 60 degrees.

Roughly 12km wide and moving at about 18km/s, the stony impactor instantly excavated and vaporised thousands of billions of tonnes of rock.

This material included a lot of sulphur-containing minerals such as gypsum and anhydrite, but also carbonates which yielded carbon dioxide.

The team's calculations estimate the quantities ejected upwards at high speed into the upper atmosphere included 325 gigatonnes of sulphur (give or take 130Gt) and perhaps 425Gt of carbon dioxide (plus or minus 160Gt).

The CO2 would eventually have a longer-term warming effect, but the release of so much sulphur, combined with soot and dust, would have had an immediate and very severe cooling effect.

Prof Morgan pictured with some of the rock samples drilled from beneath the Gulf of Mexico

An independent group earlier this year, external used a global climate model to simulate what would happen if 100Gt of sulphur and 1,400Gt of carbon dioxide were ejected as a result of the impact.

This research, led by Julia Brugger from the University of Potsdam, Germany, found global annual mean surface air temperatures would decrease by at least 26C, with three to 16 years spent at subzero conditions.

"Julia's inputs in the earlier study were conservative on the sulphur. But we now have improved numbers," explained Prof Morgan.

"We now know, for example, the direction and angle of impact, so we know which rocks were hit. And that allows us to calibrate the generation of gases much better. If Julia got that level of cooling on 100Gt of sulphur, it must have been much more severe given what we understand now."

The generation of what has become known as the Chicxulub Crater was an astonishing event.

The initial hole punched in the Earth would have been about 30km deep and 80-100km across. Unstable, and under the pull of gravity, the sides of this depression would then have collapsed inwards.

At the same time, the centre of the bowl likely rebounded, briefly lifting rock higher than the Himalayas, before also falling down to cover the inward-rushing sides of the initial hole. And although this violent reconfiguration of the Earth's crust took just minutes to complete, its consequences led to the fifth great mass extinction on our planet.

Chicxulub Crater - The impact that changed life on Earth

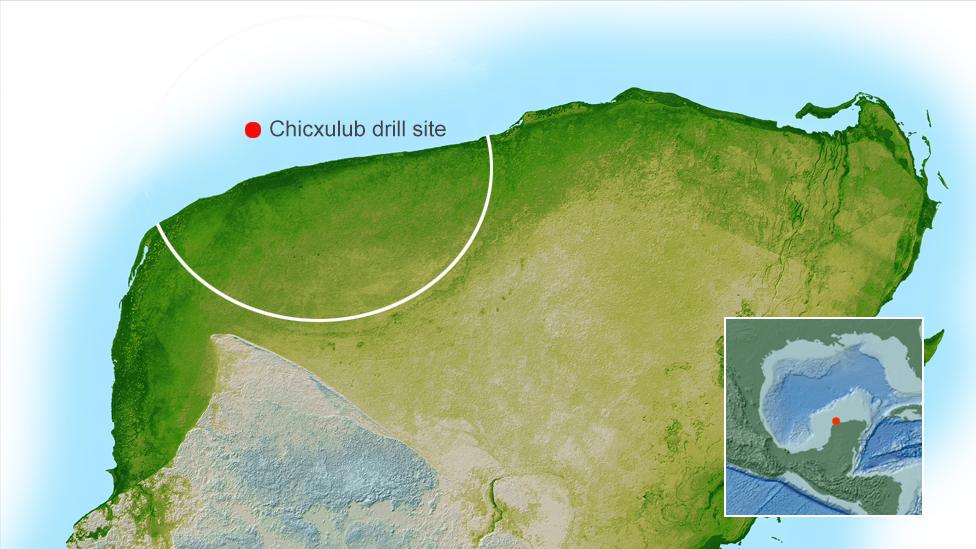

The outer rim (white arc) of the crater lies under the Yucatan Peninsula itself, but the inner peak ring is best accessed offshore

A 12km-wide object dug a hole in Earth's crust 100km across and 30km deep

This bowl then collapsed, leaving a crater 200km across and a few km deep

The crater's centre rebounded and collapsed again, producing an inner ring

Today, much of the crater is buried offshore, under 600m of sediments

On land, it is covered by limestone, but its rim is traced by an arc of sinkholes

Mexico's famous sinkholes (cenotes) have formed in weakened limestone overlying the crater

The project to drill into Chicxulub Crater was conducted by the European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling (ECORD), external as part of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP). The expedition was also supported by the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program (ICDP).

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published25 May 2016