Major expedition targets Thwaites Glacier

- Published

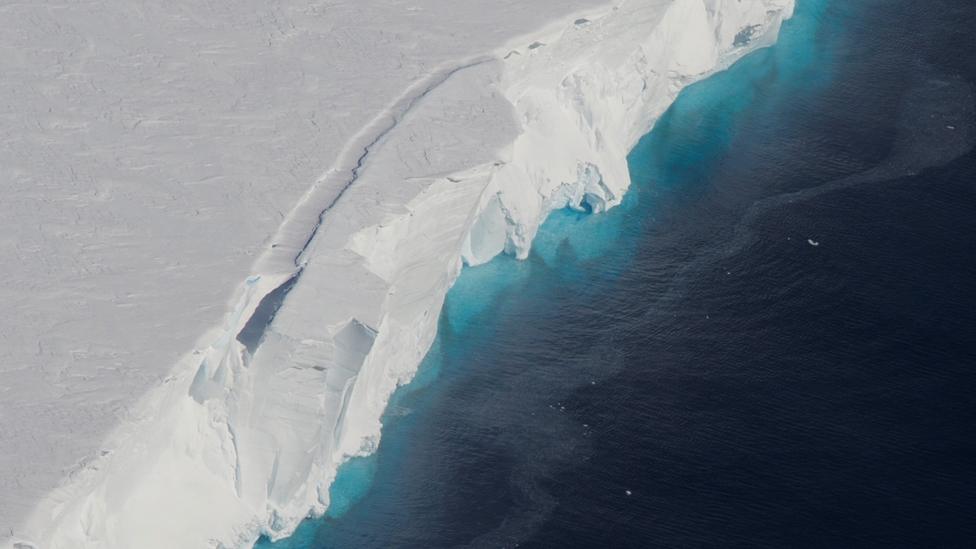

Dr Kelly Hogan: "Thwaites is the plug holding back much of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet"

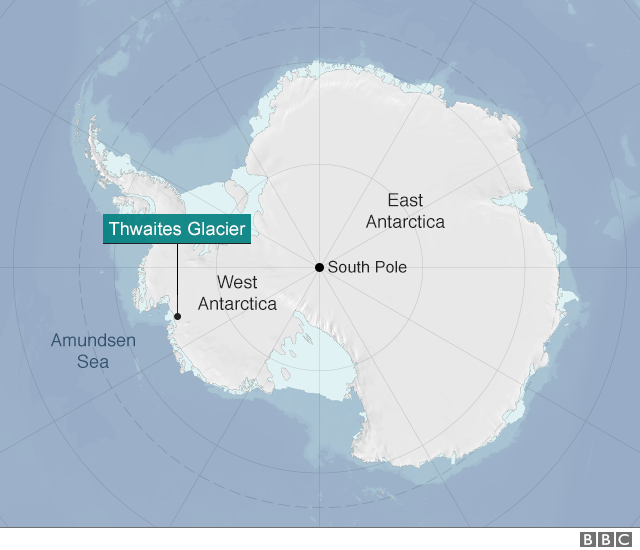

The US icebreaker Nathaniel B Palmer has left Punta Arenas in Chile to begin an expedition to Antarctica's Thwaites Glacier.

The huge ice stream in West Antarctica is currently melting, and scientists want to understand its likely future contribution to sea-level rise.

If all of Thwaites' frozen bulk were to give way, it would add 80cm to the height of the world's oceans.

"How much, how fast? That's our mantra," said Dr Robert Larter.

"These are the questions we're asking about Thwaites," the British Antarctic Survey scientist told BBC News before leaving Chile.

Dr Larter will be directing operations on the Palmer when it gets on site.

What is the purpose of the expedition?

The Palmer's 52-day cruise is just one part of a five-year, joint US-UK research programme to investigate the glacier.

Data is to be gathered in front of, and on top of the ice stream. Instruments will even be sent under its floating front, or shelf.

It's hoped that by capturing Thwaites' every behaviour, computer modellers can then better predict how its mass will respond to a warming world.

What sort of experiments are planned?

One of the studies to be conducted off the Palmer is a seal-tagging exercise.

Marine mammals will be captured on islands near the glacier and fitted with sensors.

When seals are released to dive in the vicinity of Thwaites, they'll report back on seawater conditions.

"Weddell and Elephant seals like hanging out near the ice front or under ice shelves, places we as humans can't go," explained Dr Lars Boehme from St Andrews University.

"The sensors record details about the seals' immediate physical environment, which gives us a clearer picture of the current oceanic conditions in these remote and inaccessible places."

The tags gather valuable data before falling off when the seal moults

Why is there such interest in Thwaites?

Thwaites, which is comparable in size to Britain, is what's termed a marine-terminating glacier. Snows fall inland and these compact into ice that then flows out to sea.

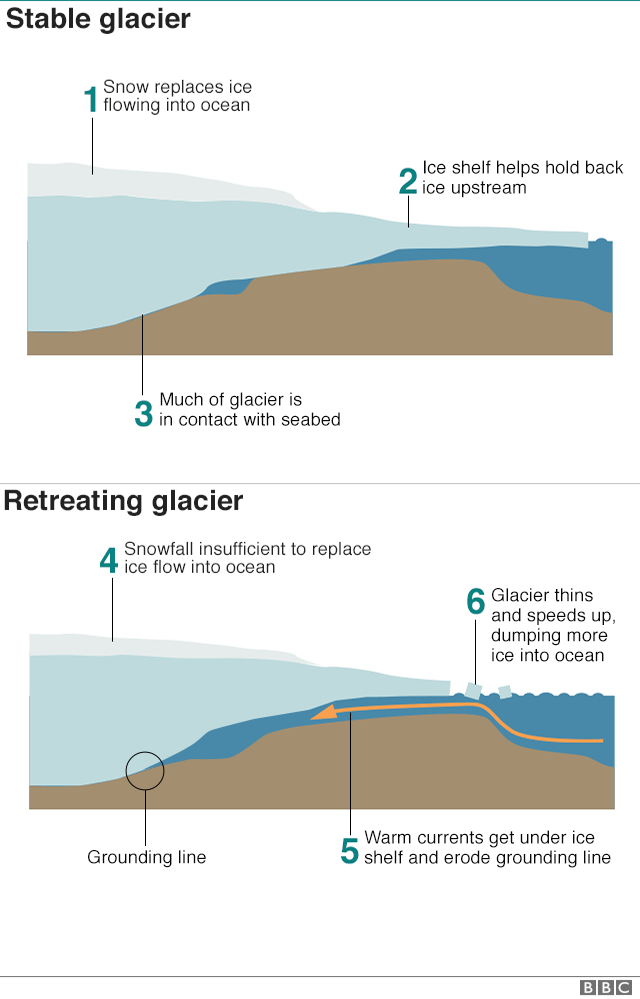

When in balance the quantity of snow at the glacier's head matches the ice lost to the ocean at its front through the calving of icebergs. But Thwaites is out of balance.

It has speeded up and is currently flowing at over 4km per year. It is also thinning at a rate of almost 40cm a year.

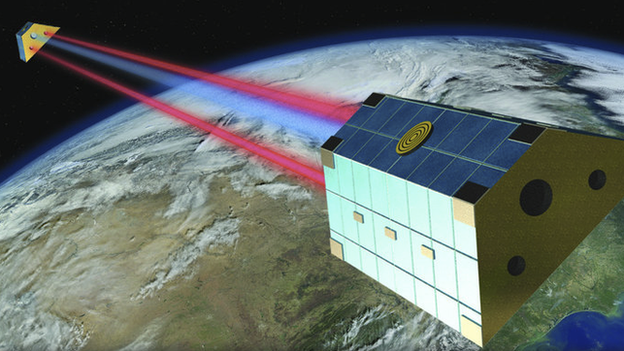

Satellite data suggests Thwaites alone accounts for around 4% of global sea-level rise - an amount that has doubled since the mid-1990s.

What is 'marine ice sheet instability'?

It appears warm water from the deep ocean is getting under Thwaites' ice shelf and eroding the grounding - the point at which the ice stream becomes buoyant.

The problem for the glacier is its geometry. A large portion of it sits below sea level, with the rock bed sloping back towards the continent.

This produces what scientists refer to as "marine ice sheet instability" - an inherently unstable architecture, which, once knocked, can go into an irreversible decline.

Some scientists have argued that Thwaites is already in this state. The joint US-UK programme aims to test all assumptions.

"We have fantastic measurements over the past 25 years from satellites and from research vessels that have visited the region, but we need to extend this record to centennial timescales," explained Dr Kelly Hogan.

"I think a lot of people think what we are seeing anthropogenic (human-driven) change, but we don't yet have all of the links in the chain to say that definitively."

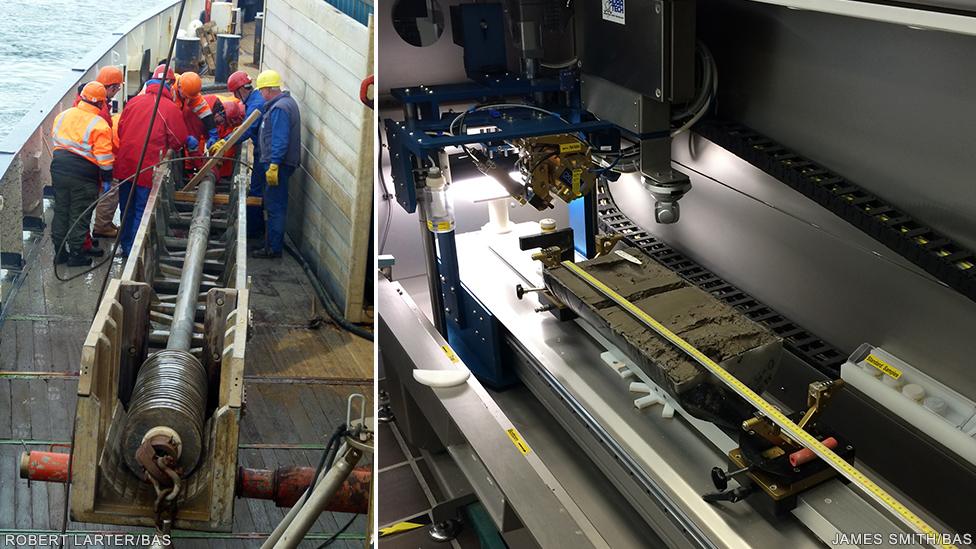

Sediment cores will reveal the past history of Thwaites Glacier

Dr Hogan will be taking sediment cores in front of Thwaites.

The fossil contents and chemistry of these muds can be used to deduce the past position of the glacier and the ocean conditions it was encountering - perhaps as far back as a few thousand years ago.

US collaborator Dr Rebecca Totten Minzoni, from the University of Alabama, said: "By discovering the history of Thwaites Glacier under past climate and ocean conditions, we can assess the stability of the glacier today.

"With the majority of the global population living at the coast, including important cultural and industrial centres like my hometown of New Orleans, we need to know how much this vulnerable region of Antarctica will contribute to sea-level rise over the coming decades."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published24 January 2019

- Published21 January 2019

- Published14 December 2018

- Published13 June 2018

- Published22 May 2018

- Published30 April 2018

- Published3 April 2018

- Published12 May 2014