Antarctic base opens briefly as berg watch continues

- Published

It's eight months since someone last stepped inside the base

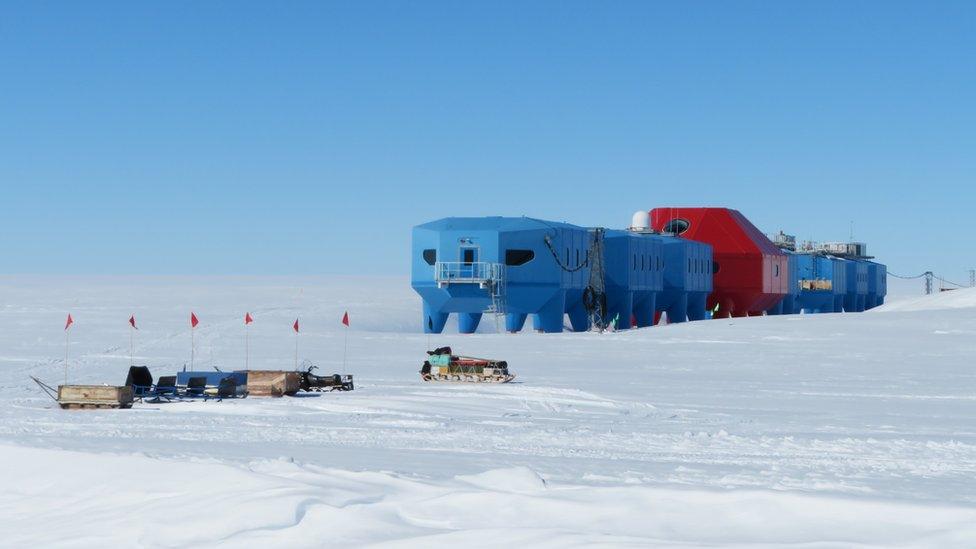

A small party of engineers has opened up the UK's Halley research station in the Antarctic.

The base had been "mothballed" - in part because of Covid, but also because the nearby ice could soon calve one or more giant icebergs into the ocean.

The British Antarctic Survey is trying to avoid having staff in the base when this happens for safety reasons.

But some maintenance still has to be performed and a suite of autonomous scientific instruments needs servicing.

The party of seven, soon to be joined by three more individuals, will only stay until mid-February before shutting Halley down again.

Halley VI station sits on a floating platform of ice known as the Brunt Ice Shelf. This platform is an amalgam of glacier ice that has pushed out from the land into the sea.

The shelf has developed a number of cracks over the years. The widening of two of these, dubbed Chasm 1 and Halloween, prompted BAS in 2017 to move Halley to a more secure location. The whole station was dragged on skis over 20km upstream.

Whether an iceberg calving is imminent is anyone's guess but satellite observations in recent weeks have recorded the development of yet another (so far unnamed) crack and the acceleration in the movement of some ice areas.

Adrian Luckman from Swansea University is routinely assembling ice velocity maps using the EU's Sentinel-1 radar satellite. He has detected a new speed-up in the ice at the shelf edge. This area is marked in light pink in the map attached to this page.

A calving here is a real possibility on current trends, Prof Luckman believes.

"We have been anticipating a major calving from Brunt Ice Shelf for some years. The most obvious piece to break away has been stubbornly hanging on for months," he told BBC News.

"Stresses have recently evolved in such a way that a different, similarly sized section is now also likely to eventually break away. This second section is where the last major calving from Brunt Ice Shelf occurred back in 1971. These anticipated calving events, even if they happen in tandem, are entirely natural behaviour for ice shelves."

Flying into Halley this week over the major cracks in the ice shelf

If two icebergs do break away, they would likely each have an area of about 1,500 sq km. That's roughly the size of Greater London.

BAS has a network of GPS sensors placed across the Brunt Ice Shelf. These sensors have picked up the same movements observed by Sentinel-1. But the survey is confident that Halley itself is far enough away from the potential iceberg action to be in next to no danger.

Nonetheless, it needs more certainty about the stability of the Brunt Ice Shelf before it can once again allow more staff back into the station on a year-round basis. And this certainty will only come after the berg calving is complete.

BAS, like all the international polar research organisations, has cut back its operations during this Antarctic summer season because of coronavirus. Every effort is being made to prevent the virus' spread to the White Continent where medical facilities are limited.

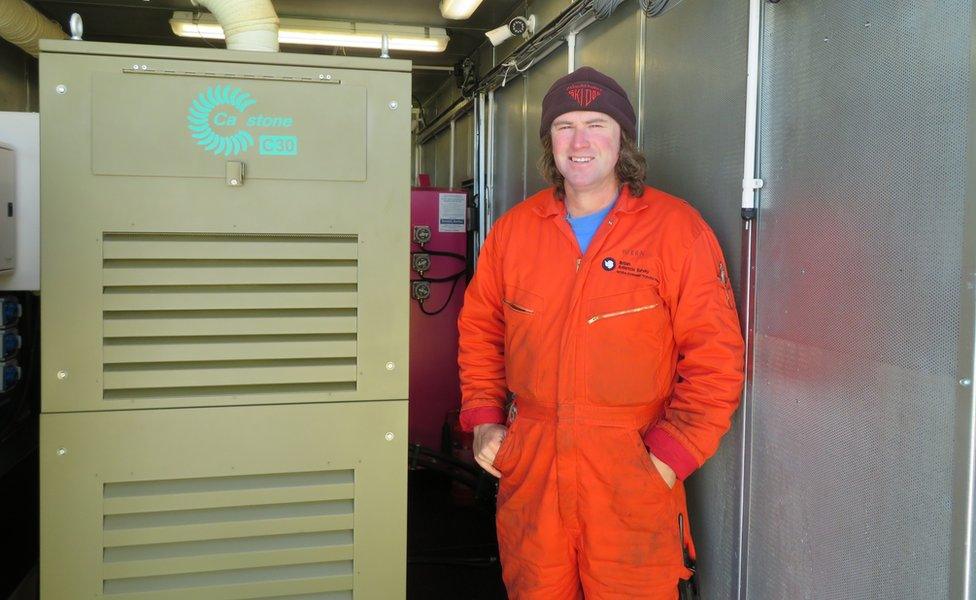

Engineer Nicholas Gregory will prep the turbine which is in the box beside him

The situation has meant not only Halley continuing its winter shutdown into the summer, but also a much reduced presence at the UK's main Antarctic facility at Rothera on the Antarctic Peninsula.

And no field research is being conducted this year.

The engineers that have gone into Halley will dig out any equipment that has been covered by snow, including those GPS sensors, and set up the station's jet turbine system for another period of autonomous running.

The turbine supplies electricity to power scientific instruments, including Halley's Dobson ozone spectrophotometer. This is the instrument that first discovered the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica in the 1980s.

The spectrophotometer needs to be observing in the period especially around September and October when the hole is at its greatest extent, external. And this is precisely the time when, in the present circumstances, no staff are on station.

The Brunt Ice Shelf is between 150m and 250m thick

The entire station was moved, module by module, in 2016/17