Emirates Mars Mission: Hope probe lines up historic Mars manoeuvre

- Published

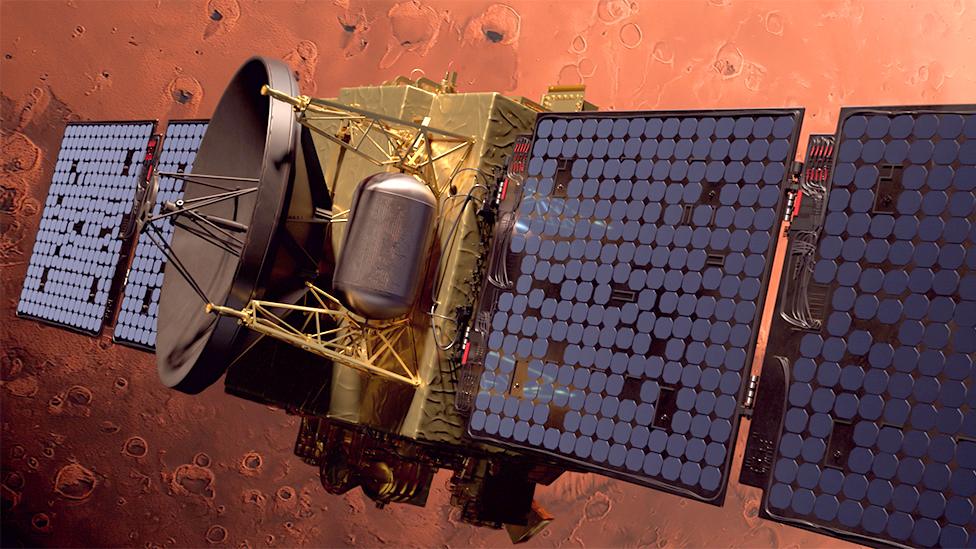

Artwork: It's seven months since Hope left Earth

History beckons for the United Arab Emirates as it seeks on Tuesday to place a probe around Mars.

The Hope spacecraft, launched from Earth seven months ago, is about to reach the decisive moment in its long journey - orbit insertion.

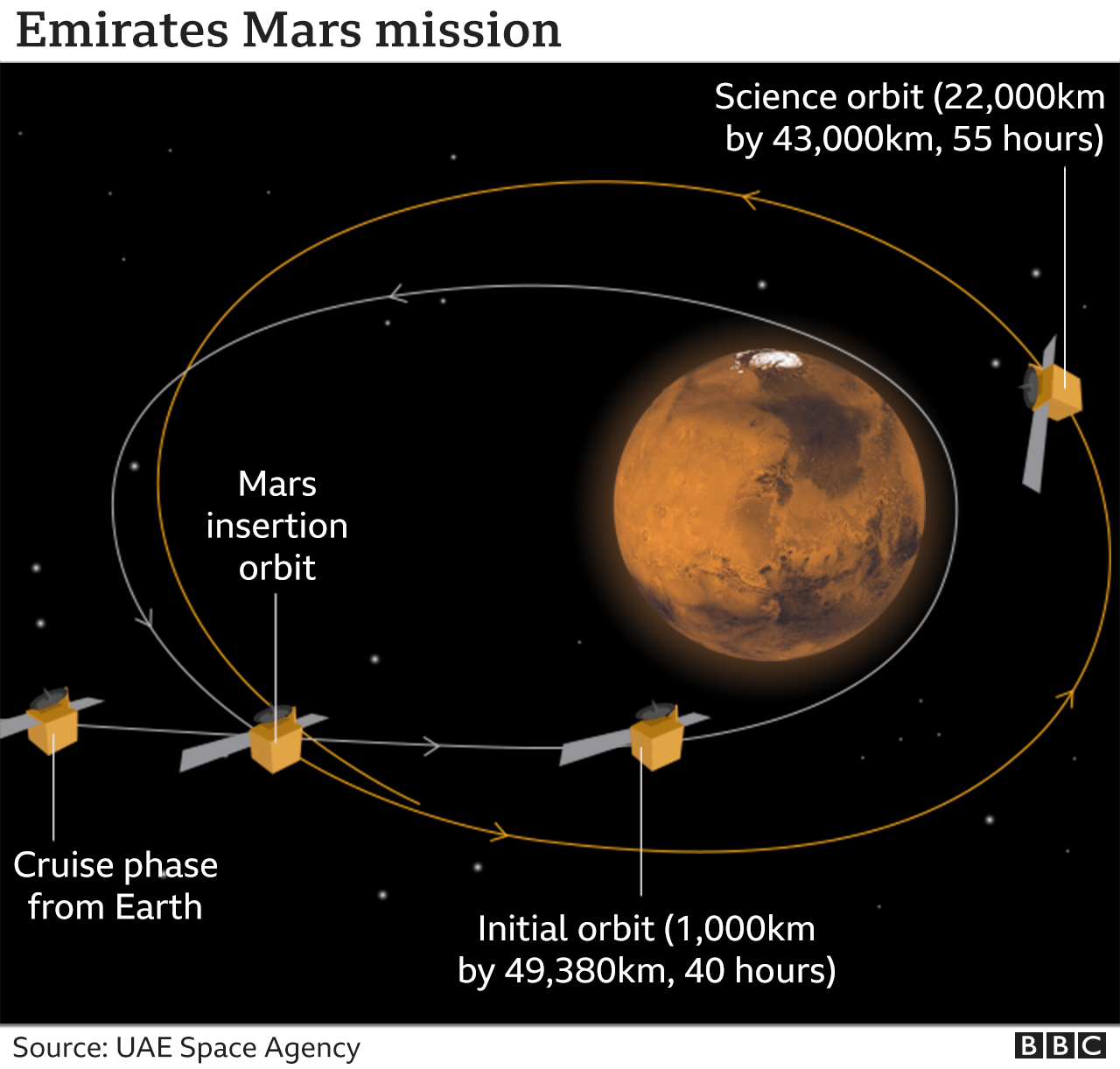

Currently moving at over 120,000km/h (75,000mph), it must fire its braking engines for 27 minutes to be sure of being captured by the planet's gravity.

Success would enable Hope to begin its mission to study Mars' climate.

"We're entering a very critical phase," said project director, Omran Sharaf. "It's a phase that basically defines whether we reach Mars, or not; and whether we'll be able to conduct our science, or not.

"If we go too slow, we crash on Mars; if we go too fast, we skip Mars," he told BBC News.

Hope is the first of three missions to arrive at the Red Planet this month. On Wednesday, the Chinese Tianwen-1 orbiter will also try to make it into orbit, while the Americans turn up on the 18th with another big rover.

For Hope, everything rides on Tuesday's orbit insertion manoeuvre. In the past couple of months, engineers have trimmed the spacecraft's trajectory so that it reaches the planet at precisely the right moment in space and time to begin the braking burn.

Mission control at the Mohammed bin Rashid Space Center (MBRSC) in Dubai will have some data streaming back on the performance of Hope's thrusters, but there is nothing anyone can do to intervene if something goes awry.

Mars and Earth are presently separated by 190 million km, meaning it would take a radio command fully 11 minutes to reach the probe - too long to make a difference. Hope must rely on autonomy to complete the manoeuvre.

"It's definitely going to be nerve-racking; just thinking about it gives me goose-bumps," said propulsion engineer Ayesha Sharafi. "But we do have a fault-protection system in place that can compensate for any problems that might happen during the burn, so I think we're in a good position for Mars obit insertion to happen successfully."

How long does it take to get to Mars and why is it so difficult?

The confirmation signal that the braking burn has started should be received at Earth just after 19:40 Gulf Standard Time (15:40 GMT). This will come through the US space agency's (Nasa) Deep Space Network of radio dishes.

Hope carries roughly 800 kilos of fuel. About half this mass will be consumed by the six thrusters involved in the 27-minute-long manoeuvre.

Shortly after the engines shut down, the spacecraft will disappear behind Mars as its trajectory bends into the planned initial orbit. Once again, there will be an anxious wait at the MBRSC while the team hangs on Nasa's dish network re-acquiring Hope's signal.

If Tuesday's efforts are successful they will be rewarded with some fascinating science in the months ahead.

The 150m-high Dubai Frame has been lit up in Red to mark Hope's arrival

Hope can be described as a kind of weather or climate satellite for Mars.

More specifically, it's going to study how energy moves through the atmosphere - from bottom to top, at all times of day, and through all the seasons of the year.

It will track features such as lofted dust which on Mars hugely influences the temperature of the atmosphere.

It will also look at what's happening with the behaviour of neutral atoms of hydrogen and oxygen right at the top of the atmosphere. There's a suspicion these atoms play a significant role in the ongoing erosion of Mars' atmosphere by the energetic particles that stream away from the Sun.

This plays into the story of why the planet is now missing most of the water it clearly had early in its history.

To gather its observations, Hope will take up a near-equatorial orbit that stands off from the planet at a distance of 22,000km to 44,000km.

Mission controllers will be monitoring closely the performance of Hope's thrusters

This means we will get spectacular images of the whole of the Red Planet on a routine basis.

"Any image we got of Mars would be iconic but I just can't imagine what it's going to feel like to get that first full-disk image of Mars, once we're in orbit," said Sarah Al Amiri, the Emirati minister of state for advanced technology and chair of the UAE Space Agency.

"And for me also, it's getting that science data down and having our science team start analysing it and finding artefacts that haven't been discovered before."

The excitement across the nation is palpable. Buildings are being lit up in red. The UAE is banking on this mission being an inspiration to its youth and Arab youth in general to take up STEM subjects in school and at higher education levels.

Hope weighs 1,350kg. About 800kg of this is fuel, half of which will be used on Tuesday

The mission was initiated six years ago to come to fruition at the time of the UAE's golden jubilee (The federation was founded on 2 December 1971). Having only recently started (2009) flying satellites at Earth, the nation didn't have the full skill-set to mount an interplanetary mission.

The Emiratis therefore approached a number of US research institutions to engage them in a mentoring role. The American institutions include the University of Colorado at Boulder; Arizona State University; and the University of California, Berkeley.

"It's been fun on a personal level, it's been fun on a technical level, and seeing everybody's personal abilities grow has been tremendously fulfilling," said Pete Withnell, the Hope programme manager at Colorado's Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics.

"There are now personal friendships that will go forward long after this mission."