Radar images capture new Antarctic mega-iceberg

- Published

TerraSAR-X pictured the new berg at 23:12 GMT on Saturday

Radar satellites got their first good look at Antarctica's new mega-iceberg over the weekend.

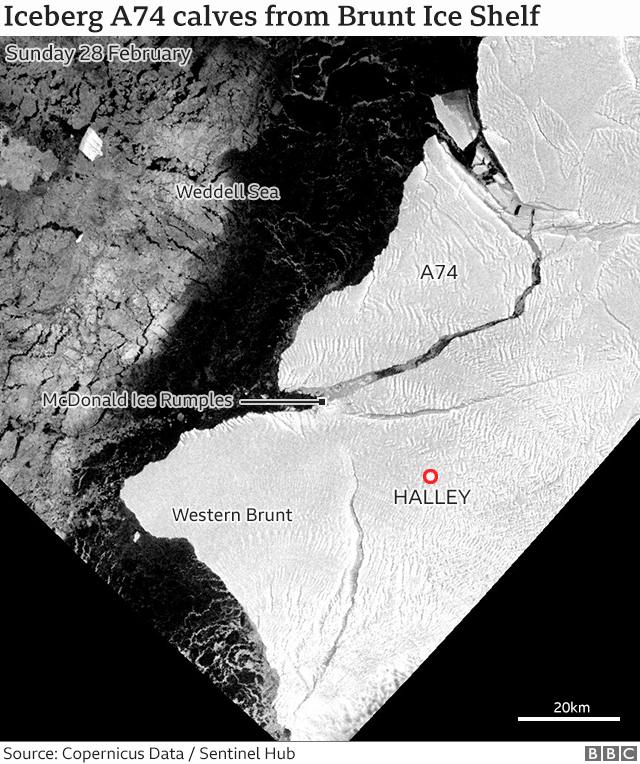

The EU's Sentinel-1 and Germany's TerraSAR-X spacecraft both had passes over the 1,290-sq-km (500-sq-mile) block, informally named "A74".

Their sensors showed the berg to have moved rapidly away from the Brunt Ice Shelf - the floating platform from which it calved on Friday.

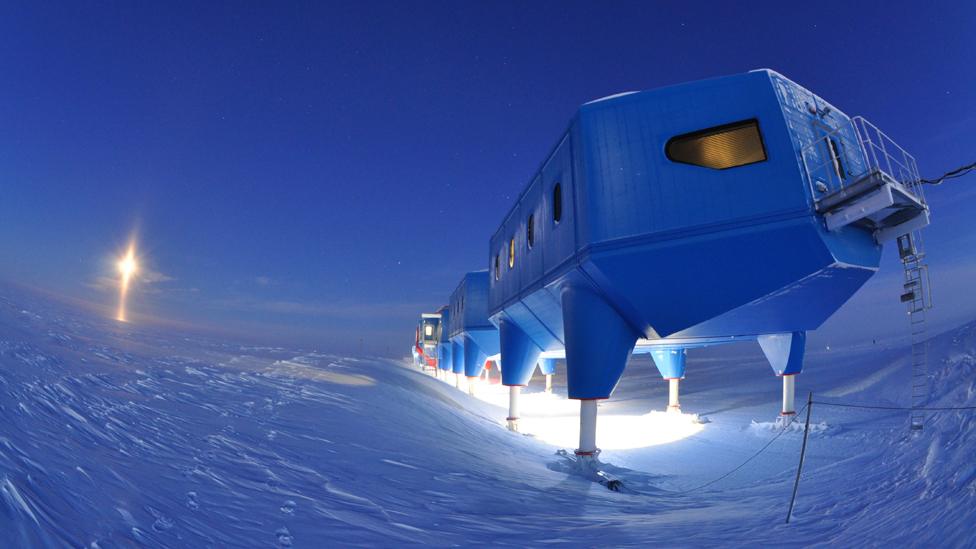

The good news is that no disturbance was felt at the UK's nearby base.

The Halley research station is sited just over 20km from the line of fracture, but GPS stations installed around the facility reported continued stability.

"We didn't think there would be a reaction simply because, glaciologically speaking, the ice around Halley is slightly separated from the area that produced A74; there's not a good way for stress to be transmitted across to the ice under the station," explained Dr Oliver Marsh from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

"Since Friday's calving, we've had a lot more high-precision GPS data that measures centimetre changes in strain along a whole range of baselines, and none of these show anything different from what was happening before the calving," he told BBC News.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Halley is currently mothballed. In part, that's because of Covid; very little Antarctic science is being undertaken at present. But it's also because BAS has been waiting to see how the Brunt Ice Shelf would behave when bergs started to calve from the platform.

A74 was the result of multiple cracks that have been developing in the Brunt - some over many years, some very recently. Friday's calving could well be the first in a series of breakaways during the coming days and weeks.

Of particular interest now is the section of the Brunt to the west of Halley. This is almost completely cut through by several wide chasms and rifts, and is only held in place by a very thin stretch of ice that's pinned to the sea floor at a location known as the McDonald Ice Rumples.

The UK has had a research station on the Brunt Ice Shelf since 1957

If this gives way, there might well be a reaction near Halley, with the ice under the station moving seaward at an accelerated rate.

But whether this section will actually calve is anyone's guess.

"This most recent calving event that now has resulted in the formation of the iceberg A74 appears quite similar to a previous event that took place in the area in September 1971," explained Prof Hilmar Gudmundsson from Northumbria University.

"In contrast, on the western Brunt, where the Halley research station is located, there are no direct observational records of a major calving event of this size since the station was erected in the 1950s. However, comparing the 1915 Frank Worsley map, produced during Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, with the calving front position in 1955, indicates the western Brunt ice shelf must have calved sometime between 1915 and 1955.

"A similarly large calving event on the western Brunt now appears imminent."

Fly along the North Rift - the crack that produced the iceberg

A small team briefly went into Halley in January and early February to do essential maintenance, and to check over the station's automated instruments, including its spectrophotometer which measures the behaviour of Earth's ozone "hole".

One of the group's jobs was to raise the Brunt's solar-powered GPS units above the fallen snow. Two of these now find themselves travelling with the new berg as it drifts out to sea.

Indeed, it was this pair's data that first alerted BAS to the calving on Friday when they reported their positions as having moved by about 100m in an hour between 08:00 and 09:00 GMT. Previously, the ice had been moving by only about 8m per day.

The German space agency (DLR) TerraSAR-X image at the top of this page was acquired in support of the Research Vessel Polarstern, which is operating in the region. The ship's scientists, led from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), are studying interactions in the Weddell Sea, external between the ice, ocean and atmosphere.

Where exactly is this?

It is on the Brunt Ice Shelf, which is the floating protrusion of glaciers that have flowed off the land into the Weddell Sea. On a map, the Weddell Sea is that sector of Antarctica directly to the south of the Atlantic Ocean. The Brunt is on the eastern side of the sea. Like all ice shelves, it will periodically calve icebergs.

Just how big is the new berg?

The latest satellite measurement puts it at around 1,290 sq km. Greater London is roughly 1,500 sq km; the Welsh county of Monmouthshire is about 1,300 sq km. That's big by any measure, although not as large as the monster A68 berg which calved in July 2017 from the Larsen C Ice Shelf on the western side of the Weddell Sea. That was originally some 5,800 sq km but has since shattered into many small pieces.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external