UK science minister 'wants strong European ties'

- Published

- comments

Britain's new science minister George Freeman has given a clear commitment to European collaboration on research.

Speaking at the launch of a new UK space strategy, external he said international collaboration was vital in helping to advance this fast-growing sector.

And he said this meant, in particular, strengthening ties with Europe, not diminishing them.

The minister is keen to "land" as soon as possible associate memberships to key EU science programmes.

These include the multi-billion-euro HorizonEU framework on R&D across Europe, and (directly in the context of space) the Copernicus/Sentinel Earth observation system.

"As a very strong Remain campaigner in 2016, part of my mission here is to make sure that we deliver a very strong collaboration with Europe, both through the European Space Agency and through a number of other programmes," Mr Freeman said.

"[We want space to be] the first area in which we demonstrate very clearly that the UK might have left the European political union, but we're not leaving the European scientific and cultural and research community. Far from it.

"In fact, we want to make sure that post our withdrawal from the EU, we become an even stronger player in that research community. I mentioned Copernicus, specifically - we see it as a vital part of the ecosystem," he told BBC News.

British companies expect to be part of European industrial consortia

The Brexit agreement between Brussels and London made provision for the UK to stay within the science programmes of the EU, but, nine months after Britain's withdrawal from the Union, the protocols have yet to be tied down.

It's hoped the publication of a new space strategy and a supporting budget in next month's Comprehensive Spending Review will clear the way for a Copernicus association at the very least.

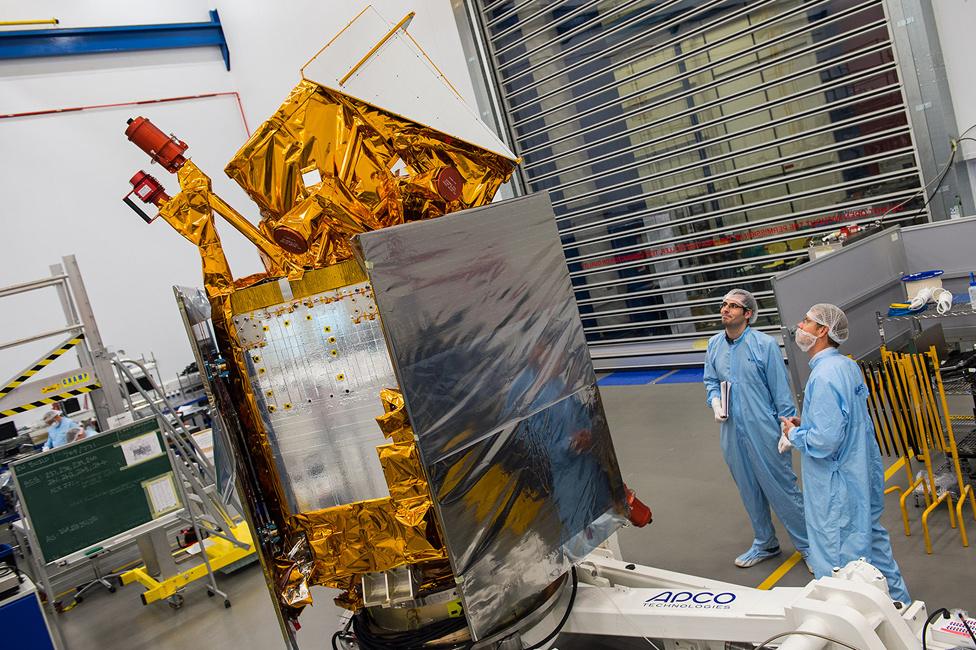

This can't come soon enough. A number of British companies and universities are worried that unless matters are sorted soon, they could be edged out of lucrative industrial contracts to build the next wave of Sentinel satellites.

Mr Freeman used the first day of the virtual UK Space Conference to announce the new space strategy. He himself was speaking down the line from the Harwell science campus in Oxfordshire, which has become the bustling home to a troop of young space companies.

He wants the government's new strategy to put boosters on theirs and others' efforts, by creating the right environment for innovation and bringing in more supporting private finance.

UK start-ups like Isotropic Systems are developing antennas that can talk to any satellite at any altitude

The strategy seeks joined-up thinking in government, and presents itself as a dual initiative between the civil and defence domains. Some issues, such as cyber-crime and satellite interference, very obviously have overlap.

The strategy also outlines how the UK can take particular advantage of high-growth areas. At the forefront of these right now is satellite broadband, which would play off the government's recent $500m (£365m) investment in the OneWeb communications constellation.

But there are emerging markets, too, in areas such as in-orbit servicing and space debris removal. The strategy wants a focus on these fast risers.

And there are targets to shoot at in the strategy. There is a goal that would see the UK become the leading provider of commercial small satellite launches in Europe by 2030. Regulations have been cleared to allow rockets to lift off from Britain starting next year.

London-headquartered OneWeb is launching a constellation to deliver internet connections

The government has had a long-term goal to see the UK take a 10% share of the world space economy, and in the early 2010s Britain was growing more quickly than the international competition in this respect. But momentum was lost at the end of the 2010s, and the UK's current share of the world space economy stands at just over 5%.

Rebecca Evernden, director of space at the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, told the UK Space Conference that the 10% target no longer served the purpose it once did.

"We concluded that we needed a more sophisticated way to actually measure growth in the various parts of the UK space sector, which is less clumsy than a single headline growth target...

"We have committed to work with our colleagues right across the sector to develop a basket of metrics approach, which will allow us to look at each sub-sector in turn, and work with those sub-sectors to set a series of goals, ambitions and metrics so that we can determine progress against where we want to get to."

However progress is measured, the strategy must become an accelerator.

The sector itself has for many years called for a national space programme that is supported by a dedicated budget. Most of the civil budget funnelled through the UK Space Agency goes straight to the European Space Agency. Projects that sit outside the UKSA-Esa relationship are dependent on ad hoc funding.

Mr Freeman said he was not in a position today to announce financing to go with the new strategy. This had to wait on the Chancellor Rishi Sunak's Comprehensive Spending Review to be released on 27 October, he said.

Inmarsat, the largest satellite operator by revenue in the UK, put its weight behind the strategy.

CEO Rajeev Suri said it was time to champion the "unsung hero of the UK economy".

"Moving space up the priority list within government through the new national space strategy is most welcome and can help to unleash the UK sector to drive further green economic growth and make significant contributions to the levelling up agenda," he added.

"Such a partnership between government, industry, academia and financial services will be a powerful one for the long-term success of the country."