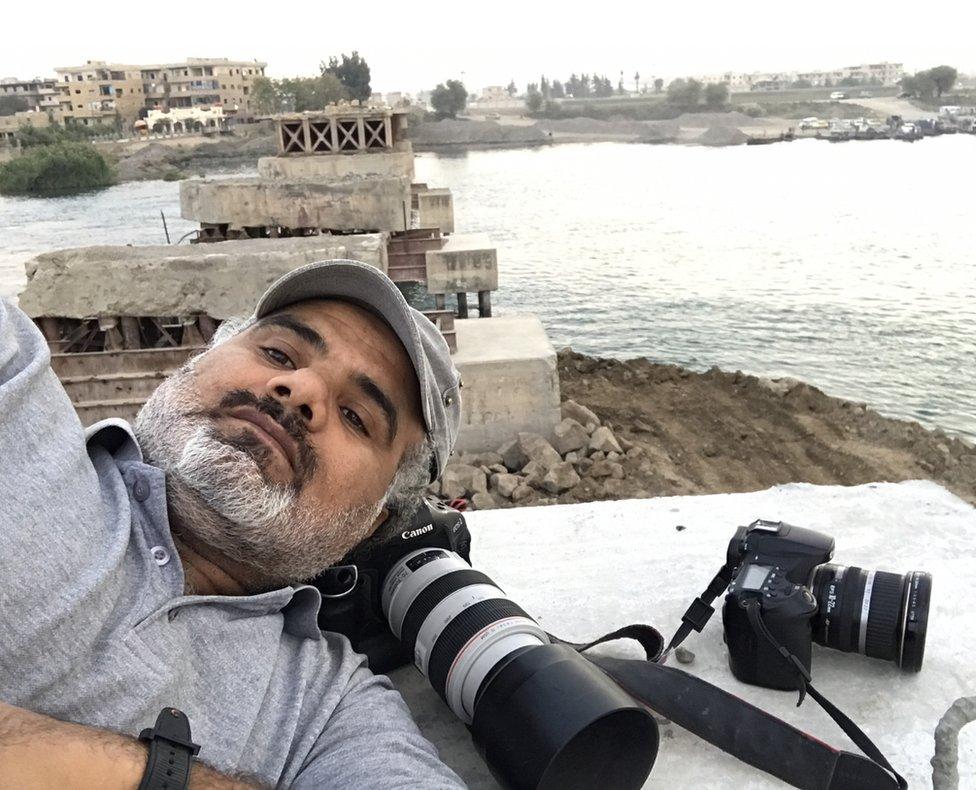

Abood Hamam: 'A picture can kill you or save your life'

- Published

For years Abood Hamam chronicled the war in Syria for news outlets all over the world without ever revealing his name - and despite being employed by different warring parties. He began as photographer to the presidential couple - Bashar and Asma al-Assad. Later he filmed Islamic State's victory parade. Now, finally, he's broken cover, to encourage exiles to return to his beloved hometown, Raqqa.

Abood Hamam laughs when asked - as a professional studier of faces - to describe himself. His looks and his personality, he says, have been shaped by the war in his country that's already lasted nine years.

"Whenever I look in the mirror, I'm astonished by how much white hair I have now," he says. "And it's all because of the war and the stress I've been living through."

Abood is only 45. But he lives his life on a tightrope, in constant fear, risking everything to bring the truth of what's happening in Syria to the world.

He's probably the only photojournalist to have worked under every major force in the conflict - the Assad dictatorship, the opposition Free Syrian Army, the rival Islamist groups Jabhat al-Nusra and Islamic State, and the Kurdish-controlled SDF.

"A picture can kill you, just as a picture can save your life," he says.

He feared his secretly taken photos of rebel attacks in Damascus, early in the uprising, would get him killed by the secret police, the Mukhabarat, if they found out what he was doing. At that stage the regime was keen to hide the rebels' growing military strength.

And later, his camera skills may have helped keep him alive when the Islamic State (IS) needed him to record the military parade celebrating their takeover of his home city, Raqqa.

Abood's remarkable story begins amid the rolling fields around Raqqa - the subject of many of his pictures - where his father was a farmer.

"To be honest, the society I grew up in, and also my parents, they didn't really appreciate journalism or photographers. They would have preferred me to be a teacher or a lawyer," he says. "They thought photographers, it's just a silly job."

But Abood became hooked when his elder brother gave him his first camera, a Russian-made Zenit.

He graduated from the School of Photography in Damascus, and ended up, before the uprising of 2011, as head of photography at the state news agency, Sana, a propaganda arm of the government.

Part of his job was to record the official comings and goings of President Bashar al-Assad and his wife, Asma.

Despite the image she cultivated as a down-to-earth First Lady, eager to talk and listen to ordinary people, Abood says she and her husband never spoke to him in all the time he hovered around them with his camera.

"On official missions we photographers were always accompanied by senior army and intelligence officers," he says. "I hated it, because you had to deal with them in a certain [respectful] way, and that's just not my character."

When the mass street protests of 2011 turned into armed insurrection, Abood began to live a terrifying double life. By day he helped polish the regime's image with his official photos. By night and at dawn, he secretly recorded the opposition Free Syrian Army's attacks in the capital.

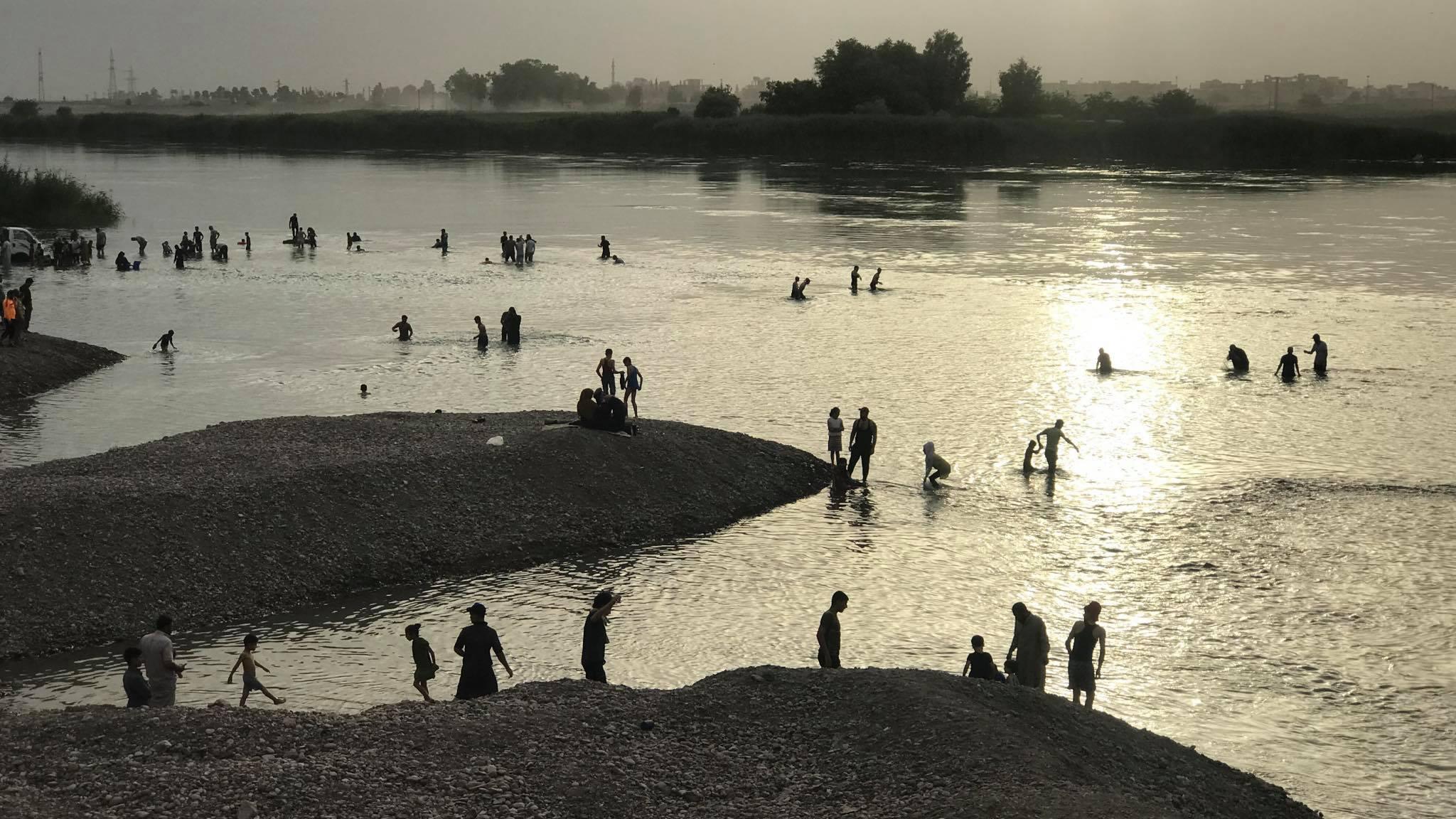

He sent his pictures to international news agencies using a pseudonym, Nur Furat. Furat is the Arabic name for the River Euphrates which flows through Raqqa, where Abood likes to relax when he gets the chance - he calls the river his "therapist". Up till today, he says, the outlets that published his pictures don't know his real name.

A body lies on a Damascus street in 2012

But soon, it became too dangerous to continue. "The memory stick that I sneaked in my pocket after covering these events that I wasn't allowed to cover, I always thought of as a bullet that would kill me if I was discovered," he says.

In 2013, after Raqqa became the first provincial capital in Syria to fall to the rebels, Abood escaped from Damascus and returned home. He had defected. But life as a photojournalist there was no less risky. He feared the many rebel forces jostling for control of the city would suspect him of being a regime infiltrator.

Then, in mid-2014, his position became more precarious still.

"I saw cars and motorcycles roaming the streets with black flags. Someone approached me and said, 'This is the new Islamic caliphate.' And I didn't know what that meant. What was this caliphate?"

When IS took over, most journalists fled. Abood, a former servant of the Assads, should have been in more danger than most. But he stayed - and went on working. Extraordinary footage discovered later in the mobile phone of a dead IS fighter shows him in a long beige galabiya gown filming at a road junction - the snapper snapped.

Abood Hamam seen filming IS takeover of Raqqa

But then Abood got an offer he couldn't refuse. IS asked him to film their victory parade, when captured military hardware decked in black flags rolled through the streets.

His pictures were used in an IS propaganda video and sent to international agencies.

Many more followed of life in the "caliphate", though Abood says he avoided public executions, even staying indoors on days they were held.

"I never swore allegiance to IS and I never had to. I built a strategy to remain independent at all times."

Public prayer in Raqqa under IS

A bonfire of cigarettes

He escaped arrest he believes, because he had good contacts with tribal leaders in Raqqa who later joined IS. But in 2015, two IS enforcers knocked on his door and warned him he'd be in great danger if he carried on working. So later that year, he left Raqqa to report on the war elsewhere in northern Syria.

He only returned in late 2017, after the bombing campaign by the US-led anti-IS coalition had freed the city from the terrorists - but largely reduced it to ruins.

Listen to The Many Colours of Raqqa on Crossing Continents, on BBC Radio 4, at 11:00 on Thursday 23 July

"On the first day I was silent. I had nothing to say," Abood says. "It wasn't me. On the second day, when I went out and started taking pictures, I started crying. I was roaming the streets and crying all the time."

For months, he wandered endlessly through the wreckage of Raqqa, camera at the ready.

He became, he says, the guardian of the city, getting to know every silent, shattered street, every broken family. The UN said 80% of the city was uninhabitable; 90% of its population had fled.

Of all the sad pictures he took, the one that's affected him most shows a ruined block of flats, the walls mostly blown out, with a bright turquoise woman's dress hanging down from the edge of what was once a room.

"I felt it was a huge invasion of privacy," he says. "Because this is normally a dress that a woman wears only inside the house. The family is no longer here, there is no more happiness here, and the dress is hanging alone. It made me stand and stare as the wind blew it left and right. I thought it was hanging like someone hangs on a rope, choking to death."

Slowly, though, colour crept back into Abood's pictures as the city began to come back to life - the yellow and red signs of reopened shops, the swirling blue waters of the Euphrates dotted with bathers. Finally, he decided to come out of the shadows and showcase his photos - under his real name - on a Facebook page, Abood without Barriers, external. His mission: to encourage people to return.

"It was a kind of shout in the face of all the bad things that happened to my city. My only goal was to show Raqqa citizens who are away, that you need to look at your city differently. I know that grey has been the colour of your city. But remember how Raqqa looks in other colours, love Raqqa again and think of coming back. If you look into my pictures, you always see, even with the most extremely sad and deadly pictures, something colourful, an element of life."

The picture he's proudest of shows a girl in a bright dress smiling shyly as she holds out a plate of ripe, freshly picked plums.

She's the daughter of a man who had moved to Saudi Arabia but returned to rejoin his family in Raqqa - and contributed to the rebuilding of a local school - after seeing Abood's pictures online. Others, too, he says, have come back because of his Facebook page.

But now Abood himself is no longer in his beloved city, although he swore he'd never leave. Journalistic impulse sent him off to cover fighting in and around Turkish-controlled parts of northern Syria. And now he's scared to go home, for fear Raqqa's current masters, the Kurdish-dominated SDF (Syrian Democratic Forces), will suspect him of being a Turkish infiltrator.

He's survived the most brutal forces, yet it's the one that freed Raqqa from extremists - alongside Western allies - that he now feels he can't risk working under. It's a reminder that, with his job, in Syria, fear never ends.

"I can't think of any moment where I lived peacefully or happily in all this period. I remember, for example, how once I went filming after an air strike, and afterwards they told me my cousin was among the dead. I went back to my video, and saw his body there.

"I'm now 45 years old and, because of the war, I didn't get married. I don't have a family. I don't have a wife. And it's really sad.

"If I didn't have this camera, I would have carried a gun. I am against weapons, but I think that if I had got involved in the war just as a regular citizen, the impact of it would have been less on me.

"I'll go on taking photos of what is happening in Syria, whether miserable or happy. I want everyone to see it. But if I had the choice, I'd take pictures of wildlife in a very peaceful area. I've always dreamed of going to Switzerland… I need the peace and calm."

You may also be interested in:

When Carly Clarke was diagnosed with cancer in 2012, she set out to photograph how she changed during what could have been the last days of her life. Seven years on, by cruel coincidence, she is at her brother's side, photographing him going through the same ordeal.