Tech Know: Etch A Sketch and robotic swarms at FutureEverything

- Published

Ellie Gibson plays with a giant Etch-A-Sketch imitation game and walks among a "swarm" of motors at Manchester's FutureEverything Festival

If there was ever a winning formula to whip up interest in an invention, it must be to evoke memories of an age gone by.

So the giant Etch-A-Sketch that formed part of Manchester's FutureEverything festival could hardly fail to please.

The annual event celebrates the work of tech tinkerers and professional researchers.

Created by the MadLab inventors group, the giant doodling toy was the first thing seen by visitors to the Victoria Baths Handicraft faire - one of the main venues of the festival.

Instead of powdered aluminium being squirted along the Etch-A-Sketch screen, the Project-A-Sketch uses an Arduino microcontrolller to detect when knobs are turned to control where a line is drawn.

A computer projects an electronic representation of the toy's screen onto the Project A Sketch screen.

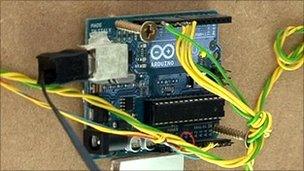

The makers' microcontroller: open source Arduino boards are used by many design enthusiasts

It has even captured the imagination of BBC engineers.

"They connected it to an Xbox Kinect motion controller during the Royal Wedding celebrations", said MadLab co-founder Hwa Young Jung.

People approaching it at the Manchester group's workshop could change the volume of a video showing the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra.

The fascination in tinkering with the established world is what drives MadLab.

Funded in part by local art bodies, this week its DIY Biology Group is waiting eagerly to see what bacteria it has cultivated on swabs taken from bus stops.

Ms Jung says "We have no idea what we'll find."

Motor swarm

Swarm of motors: Antony Hall suspended electric fans from the Victoria Baths rafters

In the drained swimming pool next door to the handicraft fair, audio artist Antony Hall was putting the final touches to a display of plastic motorised fans.

They were suspended by long cables from the ceiling and swayed above electric guitar pickups mounted, which are built to convert the sound of vibrating strings into electricity.

As the motors approached the pole-mounted pickups, they caused electromagnetic interference, making the huge room sound as though angry electric bees were buzzing about.

"The idea is for people to walk among them and adjust them", Mr Hall said. "As they swing towards you they move, so it's impossible to make them do what you want them to."

The task proved so difficult that one of the amused participants caused a collision between a pole and a fan, making one pickup smash onto the hard tiled floor.

Sound workshop

Mr Hall's residency at the Baths included a workshop for artists to experiment with electrical appliances.

Antony Hall, left, ran a sound workshop at Victoria Baths attended by artist Tony Watt, right

The group set motorised wheels cascading across the empty pool.

They introduced "brush bots" to the mix - a collection of floor and vegetable scrubbing brushes that vibrated their way across the tiles.

"We were doing a sound intervention", explained James Bloomfield, a paint artist who aims to branch out into technological pieces.

"We looked at the materials we had and we tried to fill the space (the room) with as much sound as possible."

Open data

The technique of making an everyday item work in a way it is not designed to has sparked a new fad over the last year.

Countless hacks of the Xbox motion controller have taken place since its 2010 launch.

The Lit Tree is an artistic work which uses LEDs and an xBox Kinect camera to mimic movement, as Ellie Gibson reports

FutureEverything has been sporting one such example.

The Lit Tree uses the Kinect camera to monitor the position of hands and fingers placed beneath it.

A computer processes the camera image and illuminates a tree in a pattern that matches wherever the hand is placed.

The work is part of a display about reinterpreting data.

Drew Hemment, director and founder of FutureEverything, introduced the concept of open data to the show.

The aim is to enable electronic information to be more tangible for people who are not "geeks", as he put it.

"It's making these huge data bases that public organisations now control and sit on, freely available," he said.

"It could be data on anything, from where the buses are, to the environment, to our local neighbourhoods. People can build applications and artwork on top of that".

OurCity

While some open data projects may be very technical, the OurCity project is intended to interpret information in a way everyone can relate to.

OurCity, designed by Adam Nieman and Will Simm, displays comments by members of the public and categorises them by location and whether they are positive or not

Manchester residents and visitors are being asked to pass comment on the city by text message or via a website, external.

Each message appears as a thought bubble on a table-top display, linked into the location that the observation was made.

"It's not all Coronation Street", says one. "It's a shame that witches were dunked here" says another - a reference to the city's less savoury history of drowning suspected witches.

"We're using software developed by the University of Lancaster", explains project artist Adam Nieman.

"It organises comments by theme or sentiment or actionability. We're asking about people's feelings about Manchester and the values they attribute and also their hopes for Manchester's future."

The comments provide a snapshot of life in the city, even if some may seem a little trivial.

A hot debate over whether the Arndale shopping centre is "great" or "rubbish" has ensued.

Whatever your views on such burning issues, few could argue with the sentiments of one view that floats around the display board:

"Football is more important to Manchester than other cities."

- Published30 March 2011

- Published28 April 2011

- Published1 March 2011

- Published3 February 2011

- Published7 December 2010

- Published28 October 2010