Robot trucks do the jobs Australians shun

- Published

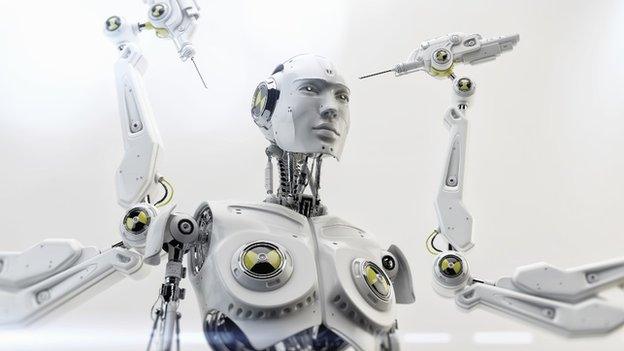

WATCH: The seven metre high mining truck driven by computer

Robots may hold the key to preventing an industrial crisis in a country whose geography makes many key jobs undesirable.

I knew Australia was big, but it didn't really hit me till I stood on a viewing platform hanging over a valley in the Blue Mountains.

As I watched the land fall away below me, giving way to a valley of forest that stretched to the horizon, I could feel thousands of miles of silence sucking me in like a vacuum.

Part of Australia's beauty is also its problem. Its untamed, uninhabited interior contains rich pickings, but there are few who want to go and get them.

"We have a labour shortage in the areas we want them, in agriculture, mining, and other primary industries," Sydney University's professor of Robotics and Intelligent Systems Salah Sukkarieh told me.

"Most of the population likes living along the coastline, along the beach," he says.

Rio Tinto says the self-drive fleet have superior fuel usage, tyre life and maintenance costs

It is for this reason, he adds, that Australia is at the forefront of field robotics.

In a country where wages and living standards are high, there is a genuine need to put machines into jobs few humans want to do.

Milk machines

Farmers are struggling to find people who want to work on their crops.

Cue Prof Sukkarieh's giant robotic weed-remover Ladybird, the farmer's new best friend, which wheels itself up and down rows of crops, analysing the vegetation, and pulling out anything that should not be there.

Spencer Kelly encountered Ladybird at the University of Sydney

And here comes Mantis, an upright robot which uses similar image recognition techniques to count the blossoms in an orchard in spring.

Come autumn, it returns to count the apples to see if the local bee-hives need to be moved to improve pollination.

Some bots have already made it out of the lab and into the mud. The Scenic Rim Robotic Dairy near Tamrookum, Queensland, is impressive for two reasons.

First, the cows have been taught to take themselves off to be milked whenever they feel like it. They queue up, walk in, wait patiently while the deed is done, and then exit back to the field.

The second is the thing that is milking them. As the cow chews the straw in the basket, an industrial-looking robotic arm shines red laser light on to the teats, which guides the cups into position.

Robotic machinery called the Lely Astronaut uses lasers to place its apparatus on cows' teats

This one is at least partly an expensive tourist attraction, with visitors lining up to watch the spectacle, but farmer Greg Dennis thinks he can get a return on his investment in six to eight years.

If the milk bots are gentle enough to milk a cow without a moo, the giant robots of the Four Hope Iron Ore Mine in Australia's north-west are something else.

Fly-in-fly-out

The ground explodes, and the rubble is loaded on to computer-controlled, self-driving trucks as high as a house, which trundle their way to the crusher.

This mine is 1,000km (621 miles) from anywhere, so far that the miners and engineers live the Fifo (Fly-In-Fly-Out) lifestyle. They arrive on specially chartered planes and stay for two weeks at a time in special camps and mining towns.

Australia is one of the richest sources of iron ore in the world

It is a lifestyle suited to a very few.

John McGagh, head of innovation at mining leviathan Rio Tinto, assures me that there will always be people employed by mining, but they will move "up the chain".

The company is working to automate its drilling and crushing as well as the dozens of mile-long trains that ship nearly a million tonnes of iron ore to the coast each day.

However, it will still need remote operators, maintenance staff and experts in mechatronics - a word I heard more than once in Australia.

Equipment controllers include ex-truck drivers, who are now based closer to their families

Whether they will be needed in the same numbers as the miners themselves is doubtful.

Cheaper bills

Automation here is partly about letting machines do the dirty, dangerous work, but also about being ever more precise about how and where they drill, how much fuel they use, what specific combination of chemicals they use to get the most copper out of the mix.

Every fraction of per cent of efficiency that Rio Tinto can squeeze out of its machines translates to millions of dollars extra profit, in higher quality extractions and lower energy bills.

The latter is a particular focus, John McGagh tells me, considering that 5% of the world's energy is used in crushing and grinding rocks.

The self-driving trucks involved in the scheme are more than 7m (23ft) tall

So what of those future mechatronics experts, and the next generation of employees, trained not in manual labour, but in remote control and computer learning?

I got to meet some of them too, although fittingly only remotely.

In one of the strangest schools I have ever visited, teachers sit in cubicles, armed with webcam, headset, microphone and two computer screens each, as they group-video-chat to classes of a dozen or so children scattered across the country.

Robot teacher

Australia has a long history of teaching children whose parents have actually chosen to live in the back of beyond, in tiny communities which don't have adequate schooling.

And it is at Brisbane's self-styled School of the Future that I meet mechatronics teacher Megan Hastie, a fizzing ball of energy who encourages each of her students in turn to run their own computer code to remote-control a small robot round a maze.

Schoolchildren control this robot via the internet as part of computer coding classes

And in Hayley Yates's geography class, I spoke to 10-year-old Ellen, who loves the peace and quiet of her home 100km (60 miles) outside the small town of Warwick, itself a remote settlement in Queensland.

She tells me she has never lived in the city, so can't imagine what it would be like. Although she does say she might like to have friends and neighbours who were close enough to see on a regular basis.

Australia's robots, then, may provide an insight into how we might all choose to live and work in the future. No matter where the work is, we can live anywhere - in the bush, or on the coast, and let the machines take the strain.

Watch more clips on the Click website. If you are in the UK, you can watch the whole programme on BBC iPlayer.

- Published10 November 2014

- Published7 November 2014

- Published30 June 2014