Does the digital era herald the end of history?

- Published

What would the world be like if we lost all our digital data?

Has the digital transformation of our society put the future of recorded history in jeopardy? Many internet observers fear so. But why, and what do they mean?

Since the 1980s our lives have grown increasingly digital, and with dizzying speed.

Most of our photos, videos, conversations, research and writings are now stored as strings of ones and noughts on local computers or in data centres distributed throughout the world.

Data specialist EMC estimates that in 2013 the world contained about 4.4 zettabytes (4.4 trillion gigabytes) of data. By 2020, it expects this to have risen tenfold.

History, in other words, has gone online.

While this means unprecedented instant access to vast stores of human knowledge and culture, it also means that mountains of digital data of crucial importance to archivists and future historians are potentially under threat from deletion, corruption, theft, obsolescence and natural or man-made disasters.

How so?

Data threats

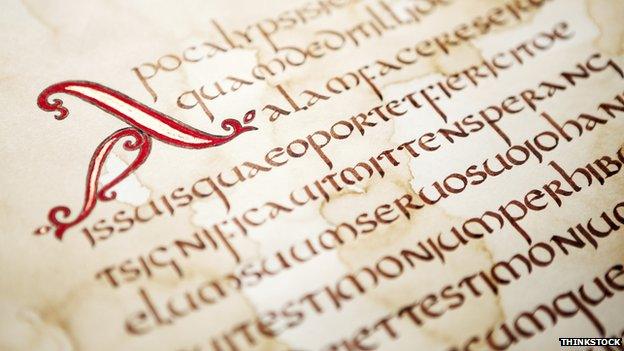

In the past, we wrote on stone, wax tablets, parchment, calfskin vellum and paper - anything we could get our hands on. And these hard copies lasted pretty well - some cave paintings survived more than 40,000 years, while Egyptian hieroglyphics date from about 3500BC.

If online medical knowledge were lost, would we return to medieval quackery?

But anyone who's seen their photo or music collections wiped out, knows how easily digital files can be lost.

A digital version of the fire that nearly destroyed the great Library of Alexandria - and many of its culturally significant books and scrolls - in 48BC, may not be as far-fetched as it sounds.

An electromagnetic pulse (EMP) from a nuclear explosion, for example, could easily wipe out entire electricity networks and effectively bring civilisation to a crashing halt. Computers, unlike printed books, need power to work.

Billionaire hedge fund manager Paul Singer warned his investors last year that an EMP was "the most significant threat" to the US and its allies.

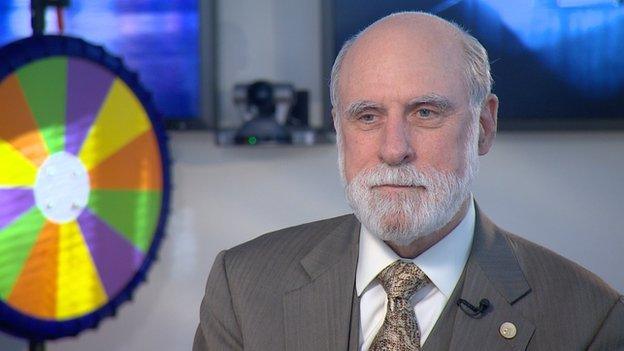

Google vice-president Vint Cerf is worried that we are not preserving our digital data properly

And in an increasingly networked digital world, the same catastrophic result could be achieved by a particularly virulent piece of malware or through state-sponsored cyber-warfare.

The loss of this data could plunge the world into a "digital dark age", warns "father of the internet" Vint Cerf - one of the inventors of the net's language and architecture.

Inaccessible

Obsolescence is another threat to this data.

Many of the earliest floppy disks can no longer be read - the data they contain has been lost forever.

If data has been written or compressed using software devised by a private sector company that has since gone bust, new technologies and operating systems may be unable to "read" or interpret the data.

But at the moment there are few museums or archives for software - the Internet Archive Software Collection, external being an honourable exception.

Do you know your bits from your bytes?

1,000 bytes = one kilobyte (kB)

1,000 kB = one megabyte (MB)

1,000 MB = one gigabyte (GB)

1,000 GB = one terabyte (TB)

1,000 TB = one petabyte (PB)

1,000 PB = one exabyte (EB)

1,000 EB = one zettabyte (ZB)

1,000 ZB = one yottabyte (YB)

(Figures are decimal, not binary)

Future generations could be faced with an ocean of well-preserved but unreadable data because they have lost the keys to interpreting it.

As it is, the latest operating systems often cannot handle files written in earlier versions. And modern web browsers are increasingly dropping compatibility with plug-in extensions like Java and Silverlight, potentially making some older websites unreadable.

"These digital formats are certainly less durable than cave paintings," says Aaron Levie, co-founder and chief executive of data management firm, Box. "It's definitely a problem. Not having interchangeable and portable data formats is a real risk."

Long-term thinking

So what's to be done?

Mr Cerf has proposed taking "a digital X-ray snapshot" of the content, the application and the operating system all together - effectively replicating the exact system as it was when the content was written.

This "digital vellum", as he calls it, has been demonstrated by Mahadev Satyanarayanan's Olive project at Carnegie Mellon University.

EMC helped digitise 82,000 manuscripts in the Vatican library

But this would require information to be digitally preserved in virtual machines in the cloud. And to achieve this "is not exactly trivial", says Mr Cerf.

Others believe the tech industry will come up with its own solutions, driven largely by market forces.

"We don't feel there's going to be a digital dark age," says Jeremy Burton, president of product and marketing at EMC.

He believes that industry-wide data storage standards will become increasingly common as storage capacity becomes less and less of an issue.

Ten years ago storage would have cost about £30 per gigabyte; now it costs pennies.

"We're likely to see a rise in digital archiving services," he says. "There's a generation of folks growing up that will expect to get access to any information they want - not just data that's been created in the last day or month, but all data."

Data storage centres are mushrooming around the world. But how secure are they?

EMC helped the Vatican digitise 82,000 manuscripts in its library - about 45 petabytes (45,000 gigabytes) of data - and used the widely accepted FITS [Flexible Image Transport System] standard specifically with longevity in mind.

It is common standards that will be crucial to protecting data for the long term, believes Aaron Levie.

Safety in numbers

So how safe is our data?

Until Gutenberg's printing press in the 15th Century, copying and distributing written works was a laborious process, so access to knowledge was restricted to an elite few.

Handwritten manuscripts were laborious to copy and vulnerable to fire

But in the age of distributed "cloud-based" computing, we can copy files ad infinitum and store mirror images of huge databases in multiple locations and keep them updated in real time.

"These days it's pretty standard to have corporate data triple replicated and geographically dispersed," says Mr Burton.

Bomb-proof data centres protected by increasingly sophisticated physical and cyber security systems are becoming more common as banks, insurance companies, governments and others with a vested interest in keeping data safe and accessible for the long term wake up to the potential threats.

But let's face it, most of us haven't a clue where Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and all the other social media providers store our data, or how securely.

We're only just beginning to understand how important this data is and what the consequences might be if we lost it.

- Published17 April 2015