Can David Cameron's extremism plan work?

- Published

- comments

David Cameron wants to push the idea of community cohesion

What does the government's counter-extremism strategy really amount to?

I've previously blogged about the strategy's controversial plans to create banning orders for extremist groups.

Prime Minister David Cameron wants to go further than create new punitive powers and, like his predecessor Tony Blair, reset the public debate on community cohesion and society's duty in combating all extremism.

The government has already introduced two fundamental changes to how it wants to prevent violent extremism.

Ministers have already cut funding to Muslim groups whom they suspect of harbouring views that are anathema to a liberal open democracy.

Secondly, public bodies including schools and universities are now under a duty to prevent people being drawn into extremism.

Mr Cameron now argues that fighting extremism demands a greater response from society by finding ways to intervene before someone has gone down the road that leads to violence - and his plans were first set out in July, external.

Boy S: UK's youngest terrorism convict - and internet played key role

Confronting the ideology and deglamourising Islamic State

He argued that his starting point was that the UK was "a successful, multi-racial, multi-faith democracy" to which Muslims had made a "profound contribution". They and wider society, he said, now need to dismantle the component parts of extremist ideology.

This is easier said than done.

For instance, the prime minister said he wants the government to work with and use people who understand the true nature of so-called Islamic State to prevent younger people listening to its recruitment sergeants.

The government is talking about new specific deradicalisation programmes and "empowering" the UK's Syrians, Iraqis and Kurds to take a lead role in speaking out.

How exactly they plan to do this remains unclear - not least because there are very few people who are qualified to carry out deradicalisation work. The recent case of a Blackburn teenager who plotted terrorism on the other side of the world shows how such work can ultimately be in vain.

The elephant in the room is, of course, the internet. Ministers are trying to persuade social media companies to spend more of their dotcom millions on crushing extremism. Many of these firms think there is only so much they can do when ISIS recruits continually relaunch themselves online under a new guise.

Ministers are talking about social media bans for extremist preachers - but research shows that militants spread the message through innovative ways that are harder to stop.

Tackling the violent and non-violent

The government wants to create powers to curtail the activity of "extremists", even if they don't break hate laws or incite violence.

Ministers argue that these people provide succour to those who want to use violence.

One of the plans is to create powers to close "mosques" where extremists meet. Just putting aside the anecdotal evidence that recruitment regularly happens anywhere but the mosque, this idea was in fact first proposed 10 years ago by Tony Blair, external.

And what that tells us is some of these proposals will ultimately come down to a fight over how to define extremism in an open society - and whether a policy aspiration can become clear and workable law. Expect serious legal fireworks in Parliament and in the courts for years to come.

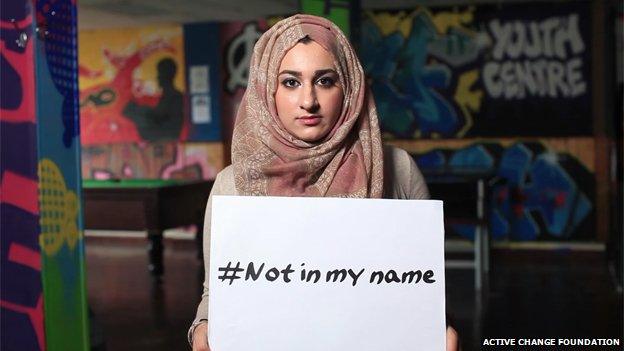

Embolden the Muslim community

Minister say extremists are overpowering normal Muslim voices.

The strategy is full of pitfalls.

Back in January two ministers, the Muslim peer Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon and the then communities secretary Eric Pickles, wrote to imams, external in the wake of the Paris attacks. Critics within the community said the letter amounted to an accusation that Muslims were "inherently apart" from British society.

The ministers believe the letter was taken the wrong way - not least because it said quite explicitly that Muslim and British values were the same.

Today's plan to throw £5m over the next six months at groups prepared to join government in combating militants is likely to face some of the same critics - but it will also be welcomed by many community organisations who are crying out for funding and support to challenge extremism where they find it.

Isolation and identity

David Cameron says he wants a more cohesive society - but that's terribly difficult to define and back-up in policy.

For instance, in July he said there would be a review of how immigrants learn English.

On the very same day, the Times Education Supplement reported the government's skills agency was cutting funding for language courses, external that were specifically targeted at integration into the workplace.

This government isn't the first to talk about improving community cohesion. Labour began debating this after the 2001 northern riots and the official report that warned that people were living "parallel lives".

So the challenge, ultimately, is whether the latest lot of ministers can do any better.

- Published9 October 2014

- Published2 October 2015