Gove eyes changes to prison governors' role

- Published

- comments

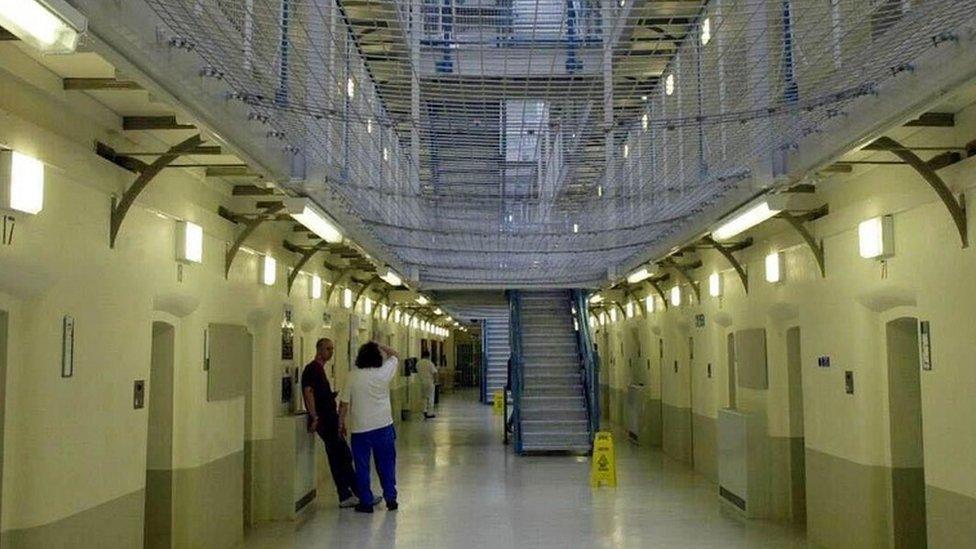

Governors of Britain's prisons lie at the heart of Justice Secretary Michael Gove's reform plans

Prison governors are not a bunch of complainers.

In many ways, they, together with prison officers, are the unsung heroes of the criminal justice system, responsible for looking after some of the most dangerous and damaged people in society.

But there is growing evidence the strain of having to fulfil their role with less money, fewer staff and more volatile offenders is beginning to tell.

A survey conducted on behalf of the Prison Governors Association, which has more than 1,000 members across the UK, suggests two-fifths will look for another job if conditions stay as they are.

The study, conducted by Steve French, senior industrial relations lecturer at Keele University, was completed by 40% of PGA members, a high response rate, he says, for such a survey.

Of those who responded:

57% work, on average, between 38 and 48 hours a week

41% work more than 48 hours

82% have seen their workload increase over the past year

61% have suffered stress-related ill health

Cause for alarm

Mr French says: "The survey paints a depressing picture of increasing working hours and workload across the PGA membership, with few opportunities for PGA members to benefit from their increased productivity and an absence of effective mechanisms for members to be able to regulate their workload."

The findings would be worrying for any employer. For the Ministry of Justice, which is responsible for prisons in England and Wales through its executive agency, the National Offender Management Service (Noms), they ought to cause alarm.

Not just because security, safety and rehabilitation might be compromised if prison governors are burned out, but because governors are at the heart of Justice Secretary Michael Gove's plans for prisons.

Michael Gove on prison plans

Michael Gove: "One of the biggest brakes on progress in our prisons is the lack of autonomy and independence enjoyed by governors"

"One of the biggest brakes on progress in our prisons is the lack of operational autonomy and genuine independence enjoyed by governors," Mr Gove says.

"Whether in state or private prisons, there are very tight, centrally set criteria on how every aspect of prison life should be managed."

The justice secretary says if governors have greater freedom, particularly over prison education, they could be "much more imaginative, and demanding in what they expect of both teachers and prisoners".

He cites the "success" of foundation hospitals and academy schools, which are also freer of central control.

"Giving governors more autonomy overall would enable us to establish, and capture, good practice in a variety of areas and spread it more easily," Mr Gove says.

No cherry-picking allowed

The plans, though, are far from fully formed. As far as prison education is concerned, it will mean untangling a maze of complex relationships.

For example, learning and skills for over-18s in custody in England is funded by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, co-commissioned between Noms and the Skills Funding Agency, and delivered by education providers via the Offenders' Learning and Skills Service.

The impact of the changes would be closely monitored to see if there was an improvement in the qualifications and skills acquired by prisoners by the time they leave, with incentives on offer for inmates - "earned release" - and for those in charge of them.

Unlike many other organisations, prisons do not get to choose their "customers"

As Mr Gove put it, "governors could be held more accountable for outcomes and the best could be rewarded for their success".

But any scheme of rewarding prison management will have to take account of the unique position jails are in - they have to accept who they are given: unlike a supermarket, restaurant or bar, the "customers" are generally people who do not want to be there.

It was a point highlighted by Noms chief executive Michael Spurr when he addressed the PGA conference this month - governors would not be able to cherry-pick the best prisoners to maximise results.

There would remain a system of "mutual support" between jails, he said, where resources, expertise and staffing were sometimes shared, and prisons would have to operate within a nationally agreed framework.

"We cannot afford to break the system down and end up with just complete competition," said Mr Spurr.

Detecting legal highs

Introducing a change as fundamental as governor autonomy would be tricky at the best of times. But these are not the best of times.

Mr Spurr said the past five years had been "incredibly difficult", with:

the Noms and prison budget cut by 24%

savings in "real" terms of £890m

a reduction in prison officers and staff of 11,000

With the cuts has come an unexpected surge in sex offenders being jailed - 700 in the past 12 months - and a rise in serious assaults on staff and inmates, much of it fuelled by the availability of new psychoactive substances, known as legal highs, or as Andrew Selous, the Prisons Minister, labels them "lethal highs".

I have written about the problem of unrest in jails before - but Mr Spurr believes the prison service has now "turned a corner" following:

a recent recruitment drive

new laws to ban people throwing objects, including drugs, over prison walls

the prospect of improved tests to detect legal highs

Mr Spurr, who started out as a prison officer, gave a strong indication there would be no further reductions in prison staffing levels or resources for day-to-day running of jails, with little difference now in the cost of comparable private and public sector prisons.

But that does not mean the justice secretary will have the luxury of smoothing the path of prison governance plans with fresh investment.

His department is "unprotected" from the austerity drive, and substantial savings will have to be made.

Some of that will come from selling off older, inefficient prisons - but the pace of that change depends on stabilising or reducing the prison population.

'Get smart'

In his party conference speech in October, Prime Minister David Cameron dropped a hint as to how that might be done.

"We have got to get away from the sterile lock-'em-up or let-'em-out debate, and get smart about this," he said, emphasising the importance of education and training to turn people's lives around - with more offenders possibly serving sentences in the community: "where it makes sense, let's use electronic tags to help keep us safe and help people go clean".

The Ministry of Justice is understood to be reviewing the use of tags, which are worn around the ankle. They can alert the authorities if someone is not at home when they should be.

Ankle tags could be an option for defendants awaiting trial

The latest satellite tracking technology, which is being tested, can monitor a person's precise whereabouts.

It is thought the most likely options for any extension of the existing tagging scheme, known as Home Detention Curfew, might involve defendants awaiting trial, more than 8,000 of whom are in jail, and offenders recalled to jail for breaching the terms of their release, of which there are about 6,000.

No plans have been confirmed - the last thing ministers want is a sudden exodus of offenders from the prison gates.

But the party that prided itself on being tough on law and order is thinking about alternatives to imprisonment.

That is quite something. And for prison governors, whose job involves managing prisoners in overcrowded conditions, that might be rather good news.

- Published16 October 2015

- Published17 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published29 March 2011