Long road to the truth for Litvinenko family

- Published

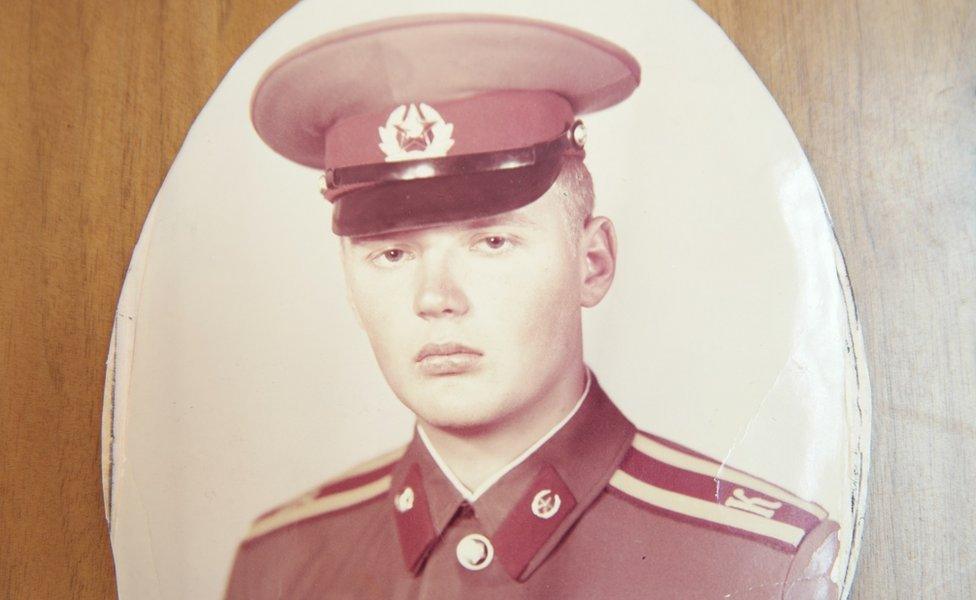

A young Alexander Litvinenko in military uniform

The image of Alexander Litvinenko defiant but dying from radioactive poisoning in a London hospital bed is how the world remembers the former Russian intelligence officer.

But that is not the way his widow, Marina, and son, Anatoly, 21, want to remember him.

The photos they spread across a kitchen table tell the story of Mr Litvinenko's life, not his death.

There is a picture of him aged 17 in military uniform. He became part of the security apparatus - what was the KGB and, after the end of the Soviet Union, the FSB.

Another picture shows him sitting astride a tank - a man who fought for his country.

Alexander Litvinenko: Profile of murdered Russian spy

But there is also an image from a press conference in which he spoke out about corruption in the FSB.

He went to see the FSB's newly-appointed director to complain, hoping he would act. But, instead, Mr Litvinenko was cast out. The director's name was Vladimir Putin.

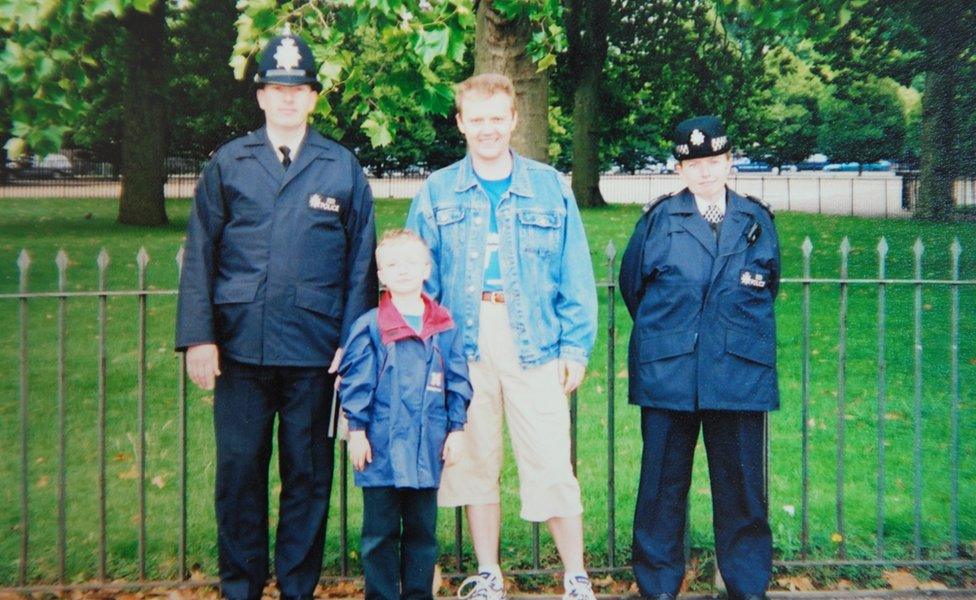

Mr Litvinenko and son, Anatoly

Alongside the pictures of his work, are those of his personal life - holding his newborn son, teaching Anatoly to swim on his back, and playing with him on a sofa. Anatoly looks away from these.

"I try not to think too much about my early childhood," he says. "It is easier that way."

Soon after speaking out over corruption, Mr Litvinenko made the decision to flee Russia for his and his family's safety.

The son of murdered Russian spy Alexander Litvinenko gives his first television interview

He arrived in London and eventually became a British citizen, in 2006.

Within weeks of that event, he would be poisoned.

The 10-year journey to the inquiry - which found that his murder was "probably" approved by President Putin - was tortuous.

An inquest began but then hit a brick wall when the government said much of the information it held was classified and could not be revealed in public.

The only solution, said Sir Robert Owen, the judge sitting as coroner, was to hold a public inquiry.

The government resisted that option, but Marina Litvinenko continued to fight through the courts.

Litvinenko (R) fought for his country

Eventually, the Home Office relented, a decision many saw as the result of a downturn in relations with Russia.

Anatoly had little understanding of his father's work when he was a child, and it was only the inquiry that helped him understand the extent to which Mr Litvinenko had remained involved in the world of security and intelligence.

This included working for Britain's Secret Intelligence Service, MI6.

The inquiry revealed how Mr Litvinenko was receiving regular payments for consultancy work and had a case officer - known as Martin - he met regularly.

The details of the poisoning itself have long been known, although fresh information did emerge which linked Andrei Lugovoi and Dimitri Kovtun to multiple attempts to kill Mr Litvinenko.

Anatoly and Alexander Litvinenko posing in a London park

Those two men have denied any role and Russia says it cannot extradite them to face charges.

One key conclusion that Sir Robert announced in his report following the inquiry was that there was "undoubtedly" a personal animosity between Mr Putin and Mr Litvinenko.

Mr Litvinenko's friend Alex Goldfarb says: "They disliked each other immensely, because Litvinenko complained about corruption… and Putin shelved his report,"

"And Putin considered Litvinenko, after the fact, a traitor for going public with his allegations."

Why targeted?

However, the specific trigger for the killing remains a subject of speculation.

Mr Litvinenko had been vociferous and outspoken in his accusations about the Kremlin from London - co-writing a book accusing the Russian security services of bombing Moscow apartments to justify a war in Chechnya.

But it may well have been his work investigating specific individuals in the Kremlin and their ties to the mafia that prompted his killing.

Alexander Litvinenko died in hospital in London in November 2006

He had already helped Spanish prosecutors arrest a number of individuals and was due to travel out to give further evidence when he was poisoned.

One of the people he had told about that work, and was due to travel to Spain with, was Andrei Lugovoi.

The issue of state responsibility has ramifications beyond the Litvinenko case.

An inquest is due to start in Surrey in the coming months into the death of Alexander Perepilichnyy.

He had come to Britain with information of corruption inside the Russian state.

Andrei Lugovoi was one of the men who met Litvinenko

It is not yet clear whether he was murdered, but Bill Browder, whose own lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, was killed in Russia, believes he was.

"Anything that potentially exposes money that the government crime figures are collecting puts the person who exposes that money at a risk of being killed," Mr Browder says.

He says not enough has been done in the wake of the Litvinenko killing.

"If the Russian government sends assassins to the United Kingdom to kill people and there are no consequences, it basically gives them a green light to keep on killing people," he says.

Mr Browder says the UK and EU should "at a minimum" impose individual sanctions such as asset freezes and travel bans on people in the Russian government shown to have any responsibility for the Litvinenko killing.

Marina Litvinenko fought long and hard for a public inquiry into her husband's death

British diplomats involved in the Litvinenko case accept the measures taken at the time may not have been strong enough to deter Russia (these included the expulsion of diplomats and the suspension of intelligence cooperation, which was of relatively small importance anyway).

But the signs are the British state may not be keen at this moment to further escalate tensions with Russia, particularly because of Moscow's role in the Middle East and the Syria crisis.

The Litvinenko case

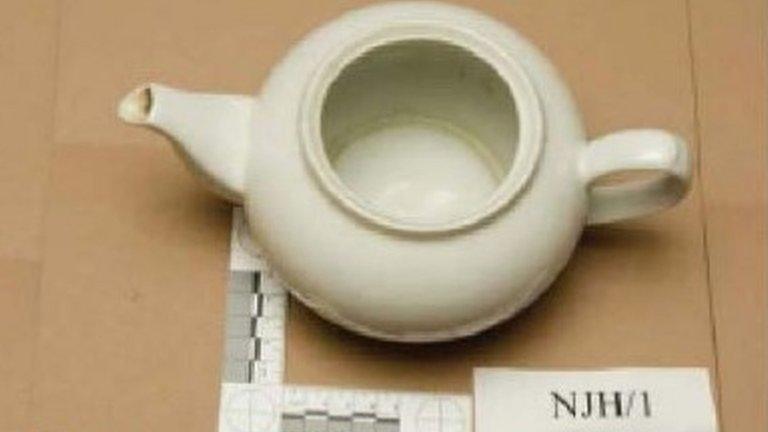

23 Nov 2006 - Litvinenko dies three weeks after having tea with former agents Andrei Lugovoi and Dmitri Kovtun in London

24 Nov 2006 - His death is attributed to polonium-210

22 May 2007 - Britain's director of public prosecutions decides Mr Lugovoi should be charged with the murder of Litvinenko

31 May 2007 - Mr Lugovoi denies any involvement in his death but says Litvinenko was a British spy

5 Jul 2007 - Russia officially refuses to extradite Mr Lugovoi, saying its constitution does not allow it

May-June 2013 - The inquest into Litvinenko's death is delayed as the coroner decides a public inquiry, which could hear some evidence in secret, would be preferable

July 2013 - Ministers rule out a public inquiry

Jan 2014 - Marina Litvinenko appears in the High Court to fight for a public inquiry

11 Feb 2014 - The High Court says the Home Office had been wrong to rule out an inquiry before the outcome of an inquest

July 2014 - A public inquiry is announced by Home Office

January 2015 - The public inquiry begins

January 2016 - Inquiry finds that the murder was "probably" approved by Vladimir Putin

Marina and Anatoly Litvinenko are aware the political context around the inquiry has changed and may shape the response.

They also recognise the report may be a milestone but might not not end their struggle.

"It is important, but it is not necessarily the end," says Marina.

And Anatoly says: "I feel a sense of duty.

"My father did a hell of a lot to get me to this country to make sure I was safe.

"I need to respect that and do whatever I can to honour his memory.

"Finding the truth is the closest we can get to justice for my father."

- Published31 July 2015

- Published28 July 2015

- Published21 January 2016

- Published26 January 2015

- Published4 March 2015