London attack: The path from violent crime to killer

- Published

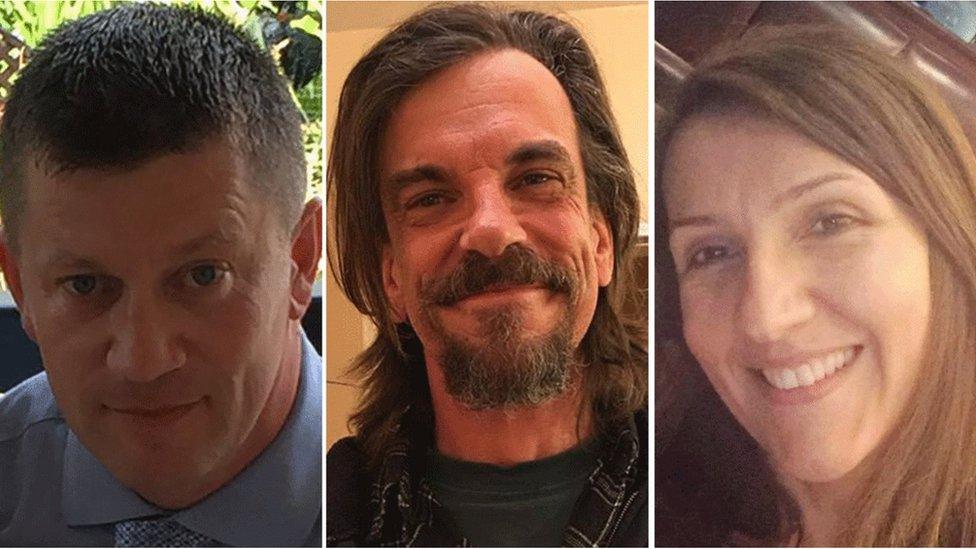

Westminster attacker Khalid Masood had a history of violence, but how typical is his past of those who go on to carry out acts of terror?

Masood, 52, who has been claimed by so-called Islamic State as a "soldier of the Caliphate", had spent time in prison for offences including violent assaults and possession of offensive weapons.

In one instance, when in his mid-30s, Masood slashed a man's face with a knife following an argument in a pub, for which he served two years.

While this criminal past may contradict stereotypes of those involved in religious extremism, Masood is only the latest manifestation of a criminal-turned-jihadist.

Throughout Europe, there has been a pattern of criminals being drawn to violent jihad.

Those who travel to Syria as foreign fighters are typically already known to police for something other than extremism.

Khalid Masood had been jailed for violent crimes

In Germany, two-thirds of foreign fighters had criminal records and more than half of those from Belgium and the Netherlands had a similar background.

Among perpetrators of terrorist attacks, criminal pasts are also common.

Berlin Christmas market attacker Anis Amri had convictions for theft and violence, and had sold cocaine in the months before the attack.

Among the perpetrators of the November 2015 Paris attacks, a number had previous convictions for robberies and drug dealing.

This is no mere coincidence, as the extremist narrative often resonates with criminals.

At the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) in King's College London, we recently published a report analysing the criminal backgrounds of European jihadists and found their radicalisation is often linked to their criminality.

Indeed, jihadism is sometimes used to legitimise further crime against "non-believers", with some extremists stating that crime and violence is permissible when living in the West.

They also claim that jihadism offers redemption from previous sins, the search for which typically comes after a period of crisis in the perpetrators' lives.

That crisis is often prompted by criminality - such as being imprisoned - but it need not be.

Masood crashed his car into railings outside Parliament

However, it is striking that Masood does not fit the typical profile of a criminal-turned-jihadist, simply due to his age of 52.

Older jihadists are usually more involved in extremist support networks - as radicalisers and recruiters, rather than as attackers.

While Theresa May said Masood had been investigated in relation to concerns about violent extremism, he was considered a peripheral figure and was not part of current investigations into extremism.

In one crucial respect, however, Masood does fit the picture of the criminals-turned-jihadists that we have examined - he was familiar with violence.

If a terrorist has a criminal background, it is very often a violent one.

Stabbings, assaults, and violent behaviour are recurrent patterns amongst perpetrators of terrorist attacks with existing criminal records.

This violent group is disproportionately represented when compared with those convicted of non-violent crimes.

For Masood, this familiarity with personal violence may have made the "jump" into ideologically motivated violence that much smaller than it would otherwise have been.

Rajan Basra is a Research Fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, in the Department of War Studies, at King's College London. Follow him @rajanbasra, external

- Published3 October 2018

- Published24 March 2017

- Published23 March 2017