Brexit: How has immigration changed since the referendum?

- Published

It looks like the government's immigration system after Brexit will make the process for EU migrants the same as for people coming from the rest of the world.

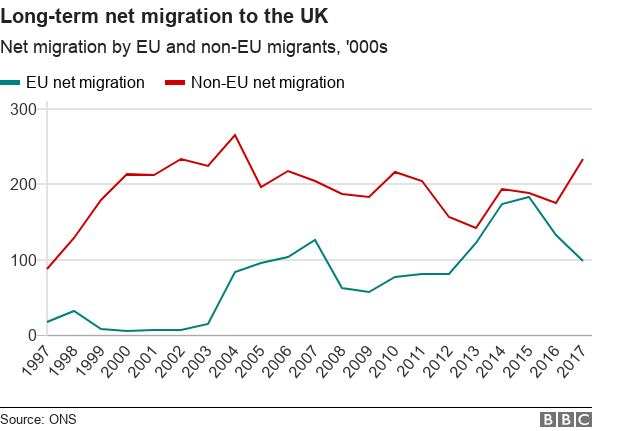

Successive Conservative-led governments since 2010 have repeated a promise to try to reduce net migration to the "tens of thousands" - in other words, to less than 100,000. Net migration is the number of people coming to live in the UK, minus the number of people leaving to live elsewhere.

This figure has not been met since 1997, when net migration was about 50,000.

The most recent figures show that in the year to June 2018 net migration was 273,000.

In June 2016, the figure stood at 336,000.

While there has been a considerable fall in net migration from European Union countries since the referendum in June 2016, net migration from elsewhere (the type the UK currently has more control over) is at its highest level since 2004.

Analysis by Chris Morris, Reality Check correspondent

The figures from the Office for National Statistics are revealing, because they suggest that ending free movement from the EU won't have a huge impact on bringing the UK's net migration figures down.

In the twelve months to June 2018, according to the ONS, the number of non-EU citizens who are in the UK on a long term basis rose by 248,000. By contrast the number of citizens from elsewhere in the EU, who are in the UK on a long term basis, rose by only 74,000.

In other words the result of the referendum has already had an impact before Brexit has actually happened. In fact in the second quarter of 2018, the latest for which figures are available, more EU citizens may have left the UK than arrived in the UK, for the first time in more than eight years (it's a bit hard to say because there's a big margin of error on the quarterly figures).

If the trend seen since the referendum continues, ending free movement will still only make a relatively small dent in the overall net migration figures.

Who's leaving?

Since the Brexit referendum in 2016, all EU net migration has been decreasing but the biggest fall has been in numbers of people from the so-called EU8 - poorer than average countries that joined the bloc in 2004, such as Poland and the Czech Republic.

EU8 net migration was two-thirds (66%) lower in June 2018 than it was in June 2016.

Net migration from the EU15 - the older, more established and typically richer members - has fallen by 40% in the same period.

Migration from the two newest countries, Bulgaria and Romania, halved to 34,000 during that time.

In 2015-16, 19% of nurses joining the NHS were of EU nationality, while in 2017-18 this fell to 8%. Meanwhile, the percentage of nurses leaving the NHS with an EU nationality rose from 9% to 13%.

Where do EU migrants work?

The Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, external looked at what proportion of jobs in different sectors were done by EU citizens.

It found about 7% of jobs overall were done by people from other EU countries. And that proportion was roughly the same across all levels of employment, from low- to very high-skilled roles.

But there was quite a lot of variation in the share of workers from EU countries once you look at different jobs, for example:

Basic construction - 34%

Cleaning - 19%

Food preparation - 14%

Construction - 11%

Basic hospitality - 11%

Personal care - 6%

Teaching - 5%

Shortage occupations

At the moment, to come to the country on a skilled worker's visa, non-EU applicants must earn £20,800 a year for entry-level workers and £30,000 for experienced workers.

There is currently a cap on the number of general workers visas available each year - something government is proposing to remove after Brexit.

More than a third of basic construction workers are from the EU

You might have heard people talking about introducing a points-based system after the UK leaves the European Union.

There is already a system like this in place for non-EU workers, with points awarded for a variety of things, external including English language skills, salary, profession and level of qualification.

The points needed by applicants increase when more people are applying for visas.

Employers must also show they've tried to find a suitable UK resident to fill the position first - another requirement government says it intends to end.

Currently there is a shortage occupation list which can mean certain workers don't have to meet all these conditions, including the salary threshold, if the visa cap has been reached.

Doctors were excluded from the cap in the summer, meaning there is no limit to how many visas will be offered so long as applicants meet the other conditions.

But not every role for which there is demand makes it on to this list.

Left-leaning think tank IPPR produced an analysis suggesting more than two-thirds of European migrant employees in health and social work would not be eligible for a visa under current non-EU rules.