South Asian diaspora recall gnawing loneliness in post-war Britain

- Published

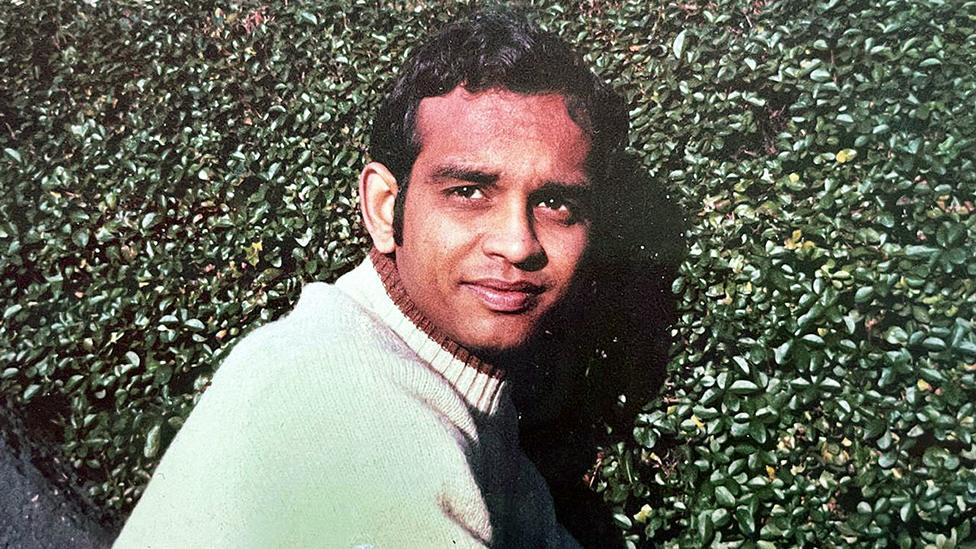

Ravi Patel could only afford to ring his father in India twice a year

The first generation who came to post-war Britain from the Indian subcontinent arrived with as little as £3 in their pockets - all the money they could bring in under strict currency controls. Their descendants, in their millions, are part of the make-up of contemporary Britain, but many of their stories are still to be told - and they reveal so much about the process of migration.

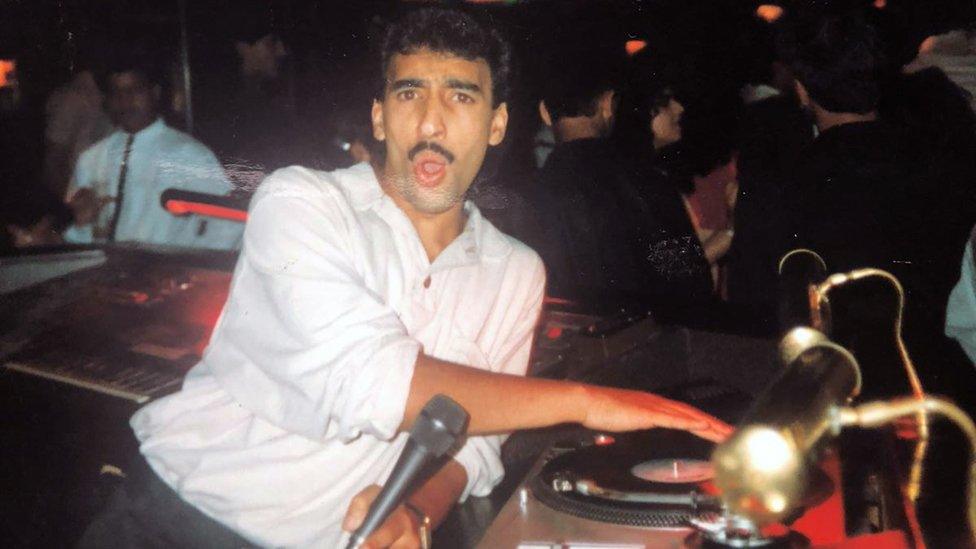

Mohammed Ajeeb arrived in Britain in 1957 from Pakistan with a battered suitcase. His first home was in Nottingham with 28 other men from Mirpur, in Pakistani-administered Kashmir. He'd had a clerical job in Pakistan but could only find work in a factory.

"I cried at night in my bed," he confesses. "I wanted to go back but I didn't want to be seen as a failure. I thought, 'I'm a determined young man, I want to succeed by hook or crook in this country,' and that carried me."

Over the years, he fought many battles for equal pay and against racism - but he stayed and went on to become the mayor of Bradford.

Mohammed Ajeeb was determined to make life in Britain a success

The 1948 British Nationality Act meant people who came from the former colonies or the empire automatically became British citizens. Britain needed workers to rebuild the country after World War Two.

Many who came in the early years from the Indian subcontinent were single, young men. They mostly worked the difficult shifts in the factories, foundries, and textile mills in places like Birmingham, Bradford, and West London. These men thought they were coming for only a few years: they never imagined generations of their family would one day live here.

Gnawing loneliness, and missing family, was part of life for these pioneers, the so-called £3 generation. Many wrote to their family on blue aerogram letters.

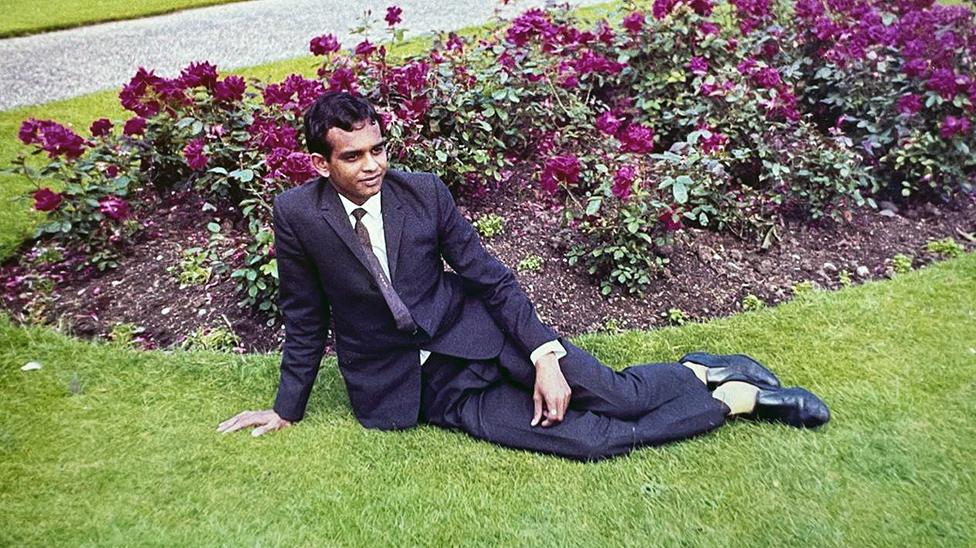

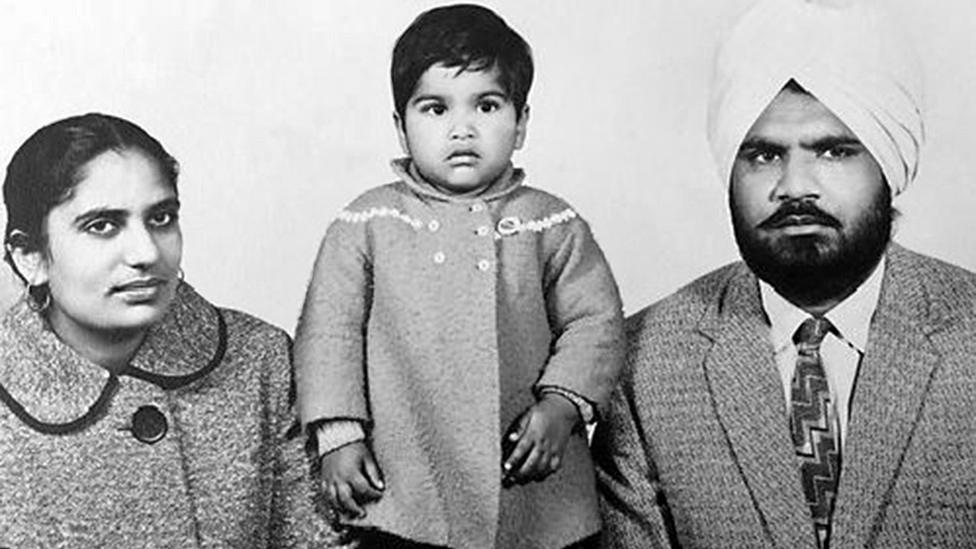

Gunwant Grewal came over from Ludhiana, Punjab in 1965. Life wasn't what she had imagined. She had been a teacher in India, but could only find factory work when she arrived.

She lived in a room in Southall, west London, with her husband and daughter in a shared house, a far cry from her spacious home in India. She desperately missed her father who she wrote to regularly.

"My tears were on my letter as I was writing. My father said, 'Why was your letter damp?' and I said, 'Oh I was having a cup of tea,' when really it was tears. But slowly, slowly it got better."

One time walking past a bus stop, she saw an elderly Sikh man who reminded her of her father. She spontaneously hugged him.

Gunwant Grewal with her husband and daughter

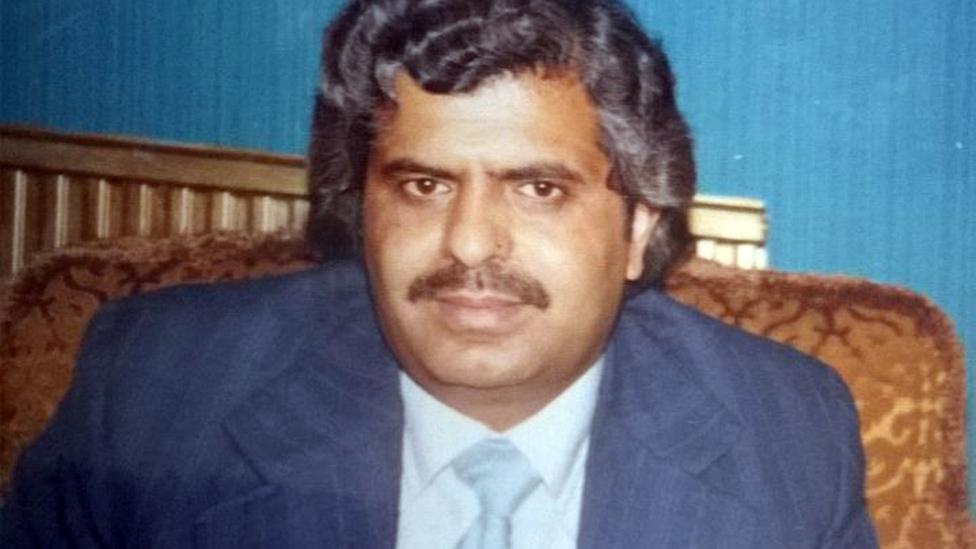

A phone call to hear a loved one's voice was out of the question. Ravi Patel arrived in 1967 with £1, having spent the rest on the journey over to Britain. He recalls that phoning India cost £1.40 per minute, a vast sum then. So Ravi called his family in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, twice a year: once on Diwali and once on his father's birthday.

It remained that way until the early 2000s, when communications were revolutionised by companies like Lebara, which was started by three British-Sri Lankan entrepreneurs and offered cheap telephone calling cards.

You could now phone the Indian subcontinent for as cheaply as one penny a minute. Decades after Ravi left India, he could now speak to his best friend whenever he wanted.

Ravi Patel spent most of the £3 he was allowed to bring to Britain on the journey over

When I started interviewing these pioneers nearly a decade ago, their experiences were not widely documented, but in recent years there has been a growing interest in the stories of people who came from the former empire and made their once colonial ruler home. And the struggles of that generation for equality and against racism are now better known.

Each generation has a different attachment to the place left and the place where they now live - but these private, and sometimes delicate, tussles between parents and children are rarely recorded.

I have been reporting on the ups and downs of the relationship between Farah Sayeed and her mother Runi, who came in 1968 as a young bride from Dhaka, East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. Farah was born a year later. Runi's generation often bore and raised their children alone, without the support of their own mothers or any wider family. For the next generation, it was different.

Runi and Farah Sayeed today

In late 2001, Farah was in Liverpool when she called her mother in London to tell her she was about to give birth. Runi says, "I started to shiver and scream because I'm her mother and I should be near." She jumped into the car and drove to Liverpool. She arrived to be told her grandchild had been born. "That was the happiest moment of my life," Runi smiles, "I am eternal now."

Waiting in the hospital corridor to see them jogged a memory. She remembered giving birth to Farah and writing a letter to her mother in then East Pakistan, saying she now realised what being a mum meant.

Runi recalled lying in the hospital bed with her newborn, in pain, and how she missed her mother who was so far away. She was hungry and wanted to be comforted by her mother's food. So when, decades later, she walked into Farah's room and met her grandson, she remembered that hunger and ache for her own mother.

She asked Farah what she wanted to eat. Chicken biryani, she replied. Runi searched Liverpool's halal shops and made that dish for her daughter.

Three Pounds in My Pocket Series 5 starts on Friday 8 April at 11:00 BST on BBC Radio 4. You can hear the previous series on BBC Sounds

Farah, after giving birth to her son, had her own revelation. "Within seconds of becoming a mum, I had a completely different appreciation of what my mum must have gone through. She didn't have any real extended family around, compared to how supported I felt."

Five years later, in 2006, Farah had another child and decided to return to London, to be near her mother. She had left the family home in 1988 wanting to get away from the burden of her parents' expectations, with a yearning to live her own life, her way.

In deciding to come back to be near her parents, she wanted to give her children something she never had - grandparents. Hers had lived in Bangladesh and she barely saw them.

Hearing Farah, I realised that there must be many thousands from the second generation, born in Britain, who grew up orphaned from their grandparents. This relationship between our children and their grandparents - the pioneers - has such a precious meaning for us, as it was something we never had.

Runi admires her three-day-old grandson Omar in Farah's arms

For Farah, life had come full circle. She wanted her children to be immersed in Bengali food, culture and language - things that were so much a part of her parents' home. It was the same home Farah had wanted to escape in the late 1980s. "When you're young, you want to fit in, and when you're older, you're just confident - fitting in matters less than the things that made you who you are."

Testimonies like these are an important part of the story of migration and the story of Britain. What began as an empire ended up with former subjects of the Raj settling as citizens, with generations now living here. Each individual making a choice about what to discard from the place left behind and what to hold on to in Britain.

Runi's husband died last year. Her voice breaks as she tells me, "It feels like you build a house and you start with one brick. I built the whole big house over the years with him. We fought, we argued. But we wanted to build that house, and we did."

He is buried near their home in London. As a young man, he wanted to rest in Bangladesh's earth, in the family plot there.

But later, he realised his home was where his children and grandchildren were. His centre of gravity had shifted.

There had been many difficult and lonely times, but now three generations were successfully established in Britain. Runi tells me she has reserved a plot next to his. "I feel that this is a big tree, solidly rooted into a land, and it cannot be pulled out."

Related topics

- Published6 December 2019