Falklands War: 'I thought I was the only one like this'

- Published

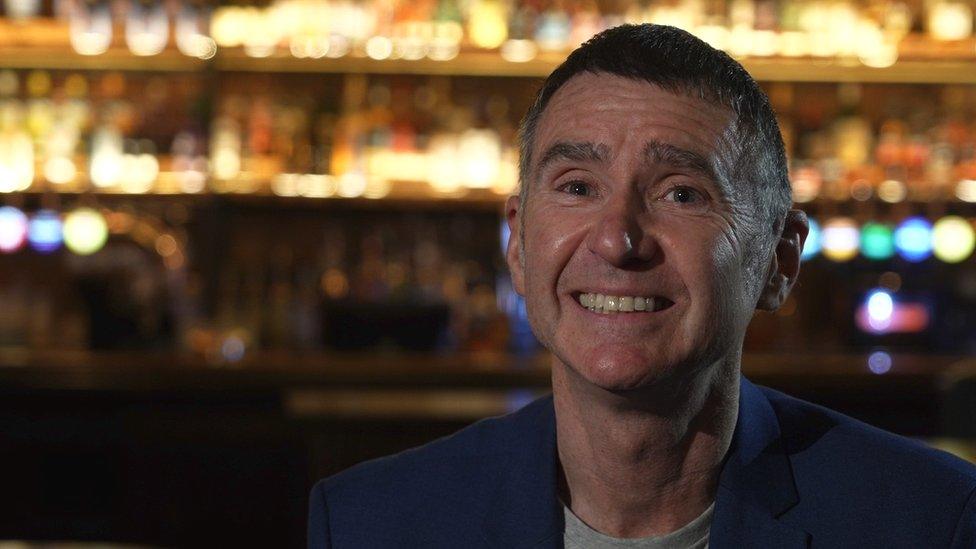

Paul Bromwell now runs a charity in Rhondda Valley

The end of the Falklands War - 40 years ago - saw a gradual change in attitudes towards how we treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Yet veterans of the Falklands are still dealing with the scars of the conflict today.

When Paul Bromwell came back from the Falklands, still in his teens, his life began to unravel. He couldn't sleep. He was drinking heavily. He flew into violent rages. "When I left the Army, I took jobs as a security guard. I couldn't sleep," he says, "I'd work three or four shifts back-to-back just to avoid going to bed."

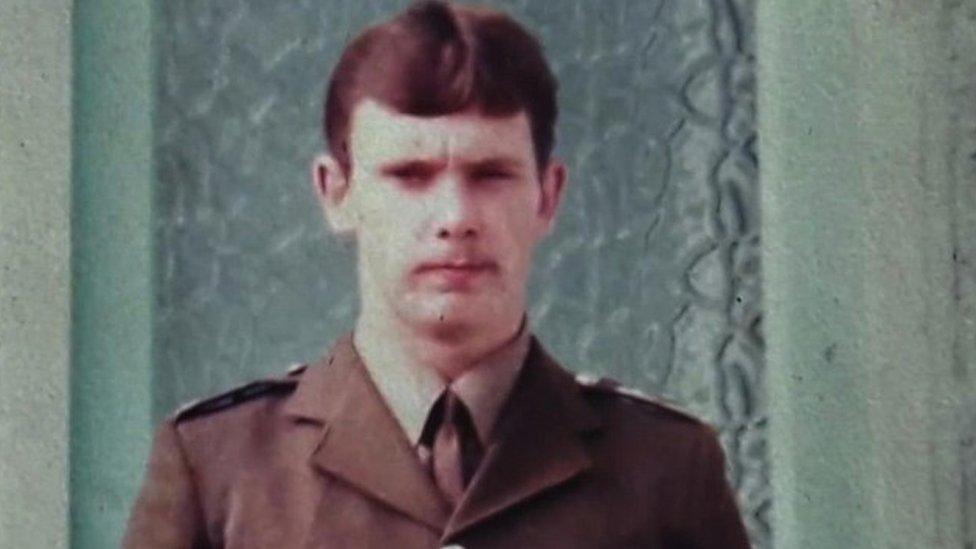

Paul served with the Welsh Guards aboard RFA Sir Tristram, a Royal Fleet Auxiliary landing ship that was struck by Argentine aircraft on the same day as the sinking of the RFA Sir Galahad. Fifty were killed in the attacks, 32 of them from the Welsh Guards.

"Just before we went out to the Falklands we had a few days leave," Paul says. "Four of us travelled back down to join the ship and I was the only one of the four who came home." It's something he never talked about with his fellow veterans.

And when he returned home after the war, he didn't fit in. "I was drinking and getting into trouble on a regular basis. I wasn't a nice person back them. Eventually I wasn't allowed to see my kids. I lost everything. It was hard".

Paul Bromwell: 'I lost everything. It was hard'

It was 12 years later that he sought help. He went to the veterans' support charity Combat Stress. "I thought I was the only one to be like this. And when I went into that group meeting at Combat Stress, half my old section was in there. That's when I started to mend myself. I started helping other people and I've been doing it ever since."

Paul founded the charity Valley Veterans, to help ex-servicemen with PTSD.

On a patch of disused industrial land in the heart of the Rhondda Valley, the organisation has built stables for four horses. It's a veteran-led effort, with about 140 active participants. The men exercise the horses, learn to ride and groom them, and help run the stables.

"I sit in the corner there and just listen to them munching the hay and it chills me out," says Paul. "But at the same time, I got all the guys up here. We're all like-minded, we're out in the open, not hurting anyone and we're trying to build something positive. The conversations we've had in our little room there - amazing."

He adds: "I think up here we go a lot further than any psychiatrist. You have an hour in a room with a psychiatrist, you don't know how to talk to him and a lot of the guys [go] straight down the pub after that. Up here, with the horses, you can talk about it if you want to - and you've somebody to pick you up."

After the Falklands attitudes towards PTSD would eventually change. Falklands veterans themselves would be the last generation for whom the condition went unrecognised and, to begin with at least, untreated.

The Sir Galahad was bombed and destroyed on 8 June, 1982

The vast majority of combat veterans do not develop PTSD and many of those that do recover in time. It's not known why some people develop the condition long-term.

The military psychiatrist Professor Sir Simon Wessely, of Kings College London, says 6% of ex-servicemen and women develop the condition. That rises to 17% among those who've seen active combat. "That's a lot less than the public thinks," he says.

It's claimed the incidence of PTSD and post-service suicide was much higher among the paratroopers returning from the Falklands than among the marines. This is frequently attributed to the fact that the paratroopers flew back and were reunited with their families within days of the war, while the marines came back by sea and had several weeks to unwind and "decompress".

"The trouble is," says Prof Wessely, "it's not true. There's no evidence to support it. It's a myth. It's quite a useful myth because there is some evidence that a decompression period can help."

In 1982, PTSD was not recognised by the British military or the medical profession. It had been identified only in the United States, among veterans of the Vietnam War. Britain had not yet adopted it as a diagnosis.

"It was only a series of civilian disasters in the 1980s - after the Falklands War - that brought PTSD awareness to Britain," says Prof Wessely. "The Zeebrugge ferry disaster, Hillsborough stadium, the Bradford fire. Usually in psychiatry, the civilian world learns from the military - with PTSD it was the other way round."

He adds: "Forty years ago, battlefield trauma was taken seriously. But the view was that if you stayed ill, long-term, then it really was a failure of character, a matter of personal weakness. It was a throwback to that Victorian and Edwardian way of thinking, and it was still there in the mid-20th Century."

"It's very unusual to hear that view today," he says. "I'm not saying it's perfect but it's a lot better than it was."

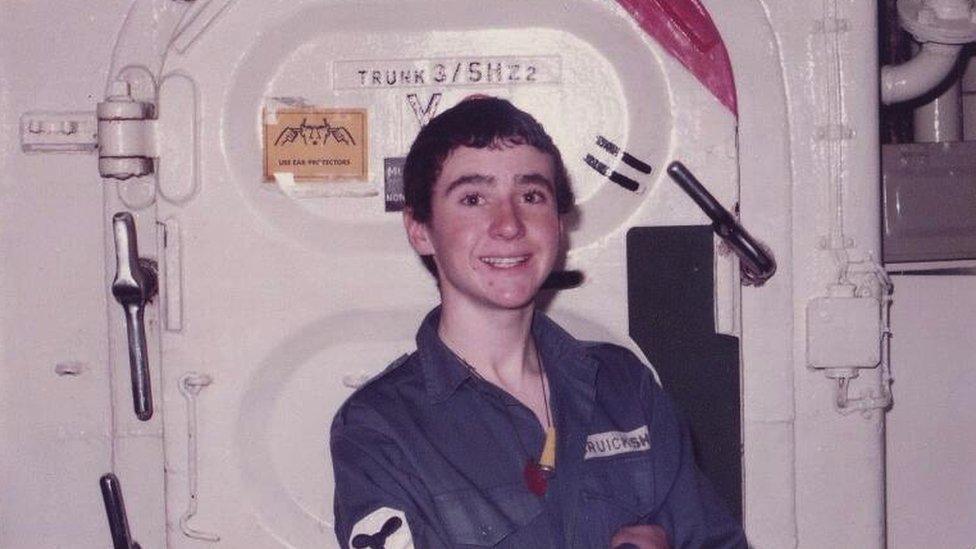

David Cruikshanks sailed off to fight in the Falklands aged 17

One beneficiary of that change is David Cruikshanks. He was in the Royal Navy and sailed to the Falklands aged just 17. When he came home he too started drinking heavily. It went on for years.

"I became a press photographer. That was a world in which alcohol was normalised. I knew there was something going on with me, but I didn't want to admit it. I didn't know how to talk about it. I became good at masking it. I joined the Navy to escape violence really. There was violence at home, at school, everywhere in my home town of Glenrothes, in Fife."

After the Falklands he started having panic attacks. "One day I thought I was having a heart attack. There was a clinic across the street from my house and I ran in there. I saw a doctor who said 'I think you've got some kind of panic disorder, or anxiety condition. I'm gong too refer you for some cognitive behaviour therapy.

"And I remember that day because I just burst out crying. I thought: 'Oh my God I don't have to pretend any more. And there's help'."

David: 'I became a press photographer. That was a world in which alcohol was normalised'

Typically it takes ex-servicemen who develop long-term PTSD years to accept that there is something wrong with them, and to seek help - evidence that the stigma remains.

In South Wales, it's not just Falklands veterans who turn up now at Paul Bromwell's stables. Men from more recent wars, in Iraq and Afghanistan can be found there too.

"I was very lucky when I went up to Combat Street first time," he says, "because I had a lot of second world war veterans who'd been through the mill and they sort of nurtured me. So I've been helping other people ever since.

"It's not about going to see some counsellor or psychiatrist," he adds. "It's about guys helping other guys. You can open up and say things because they understand."