Coronavirus: Memorial gardens planned across England

- Published

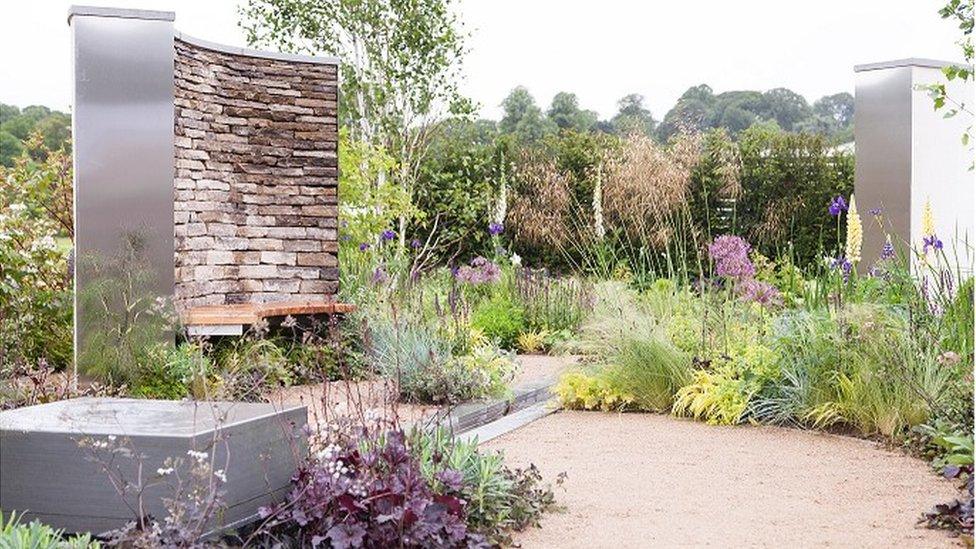

Riverside Church created a garden for anyone who lost loved ones during the lockdown period

The coronavirus pandemic has claimed tens thousands of lives across England - but how should those who have died best be remembered? Could part of the legacy of the virus be the creation of gardens and woodlands in which people can remember its victims?

During lockdown temporary memorials were created at some churches while councils have begun to announce plans for green spaces to remember people who have died.

Fundraisers for memorial gardens have sprung up on sites such as JustGiving and Go Fund Me, with thousands of pounds already being pledged to get local projects off the ground.

Andy Langford, Cruse Bereavement Care clinical director, said: "Memorial gardens can anchor people to memories of special times they spent with someone."

Fleetwood Memorial Park was one of hundreds created after World War One to give the living somewhere to remember the dead

Memorial gardens have traditionally been created to remember the victims of conflict or terrorism attacks but their background does have relevance to the current pandemic.

According to a report by Historic England, memorial parks and gardens really took off after World War One when the scale of loss and the views of returning soldiers led to memorials that took into account the needs of the living - rather than monuments that focused on the dead.

David Lambert, from the Parks Agency, which produced the report, said: "War memorial parks and gardens were mainly developed after World War One, with a smaller but still significant number after World War Two.

"Memorial woodlands, memorial sports fields, memorial avenues and roads likewise."

He said he had not come across any memorials to the Spanish flu epidemic, which began shortly after the end of the World War One when soldiers returned home from the battlefields of Europe.

Spanish flu was estimated to have killed more than 100 million people globally but has become known as the "forgotten pandemic" because of a lack of awareness of the outbreak, which occurred at a time when the world was already coming to term with the huge losses of war.

"I guess the government was keen to focus on the peace (or victory as they liked to term it) rather than on a new wave of deaths," Mr Lambert said.

Coventry's War Memorial Park was opened in 1921 as a tribute to the soldiers from the city who lost their lives during World War One

Professor Avril Maddrell, a social and cultural geographer who has researched public bereavement traditions, said: "Outside the cemetery and the crematorium the overwhelming emphasis of civic monuments has been on national pride.

"The Wellington memorial, external, for example, focuses on the military leader and famous victory."

Prof Maddrell said these monuments tended to have a class element, celebrating male public figures rather than everyday people.

"Everyday" deaths from disease were generally viewed as "par for the course", she said.

"They were expected to be borne, lived with and not made a fuss about.

"There are no memorials to the thousands of women who have died in childbirth as again it was viewed as an individual private loss, something that happens."

Talking about the most recent global pandemic before coronavirus Prof Maddrell said: "With Spanish Flu the public reaction was in part shaped by overlapping with the end of the First World War, when the focus of attention and resources was on war graves and memorialising war dead appropriately.

"There was also a national desire to focus on recovery."

The Wellington Arch in Hyde Park Corner commemorates a victory rather than focussing on the lives lost in battle

In Staffordshire a memorial garden for those who died during the lockdown was set up in April as a reminder the virus could affect anyone.

Riverside Church in Branson set up the garden with photographs and names of people who had died displayed on crosses.

Among those remembered were three members of the same family.

In Solihull Harvey Eustace, 10, met with councillor Ade Adeyemo to discuss his design for a coronavirus memorial garden in Olton Jubilee Park

In Solihull, in the West Midlands, the local council has said it wanted to create a memorial woodland.

Councillor Ade Adeyemo said he welcomed the idea of "having somewhere for local residents to be able to grieve".

In Suffolk the county council has announced plans for a "healing wood" to honour those who have died and give people access to a place for reflection.

Councillor Penny Otton said it would be "essential for people that have, over the last few months, suffered from serious mental health problems".

Cabinet member for environment Richard Rout said the authority intended to create a place where "generations to come can take refuge from their daily lives and reflect on this time, and remember those who have lost their lives".

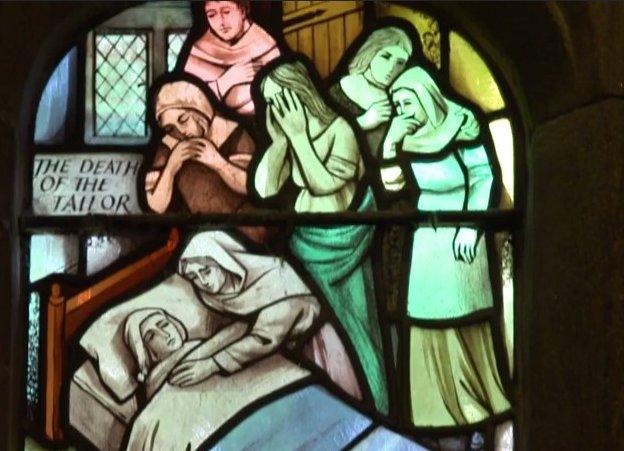

In Eyam in Derbyshire stained glass windows remember the victims of the Great Plague

Memorials to the victims of disease

Memorials to the victims of a disease outbreak are not widespread but they are also not new. In towns and villages around England plague crosses stand as a reminder of the victims of the Great Plague. Some of the most famous memorials are in the Derbyshire village of Eyam where 75% of the population died.

More recently in Liberia a memorial graveyard to the victims of Ebola, external was dedicated in 2016. As many victims were cremated it has also served as a focus point for families who do not have a grave to visit.

While there have been calls for an Aids memorial to be built in London it has not yet become a reality. There is, however, an Aids memorial quilt that includes quotes and images from family and friends of 384 people who died in the 1980s and 90s.

Though not a memorial, there is a statue, plaque and museum dedicated to physician Edward Jenner, a pioneer of vaccination who invented the smallpox vaccine.

Funeral companies have also announced plans for memorial gardens, Westerleigh, which runs crematoria and cemeteries across the UK, recently released artist's impressions of its designs for 34 memorial gardens.

Roger Mclaughlan, chief executive of Westerleigh Group, said: "The gardens will be special places, where people can come to remember and reflect, and to give thanks to the wonderful way that the NHS, key workers and whole communities pulled together during this unprecedented crisis."

More traditional memorials have also been planned, with South Tyneside Council and Barnsley Councils both announcing plans for public artwork to remember people who have died while also recognising key workers and volunteers.

Some councils have also begun to explore funding options, with the impact of lockdown on the economy and widespread job losses leaving council budgets stretched.

Portsmouth City Council recently approved plans to set up the Portsmouth Coronavirus Memorial Trust, which will consult residents on what sort of memorial they would like.

James Daly, a cultural development and projects officer at the council, said: "We would expect the trust to consult widely with the public because we know that memorials are important as remembrance but also as part of the healing process - so it's important people in the city feel ownership of it."

Prof Maddrell said there were a number of places and ways society chose to remember people, including online, through spontaneous memorials such as flowers and candles left at the site of death, or memorial benches.

"While plans for memorial gardens are springing up, and these are to be welcomed, in terms of a legacy, external, the best memorial would be better preparation and organisation to mitigate the ongoing effects of the pandemic," she said.

Cruse say memorial gardens create a sense of peace and closeness to the person who has died

A series of memorial gardens could see more public outdoor space created, at a time when the importance of access to gardens has been recognised.

Lockdown drew attention to how many people in the UK did not have access to the outdoors and also to the fact access to a balcony, garden or park had been considered a luxury when in reality it was a necessity for mental and physical health.

Mr Langford said: "A traumatic death can be at the forefront of your mind, and a memorial garden can help someone remember the good and joyous times alongside what might have been a very difficult ending.

"They can create a sense of peace and closeness to the person that has died, as well as a place to have a cry and remember how much you miss them. Both are healthy parts of the grieving process."

- Published24 April 2020

- Published28 May 2020

- Published25 July 2020

- Published20 September 2018

- Published5 November 2016